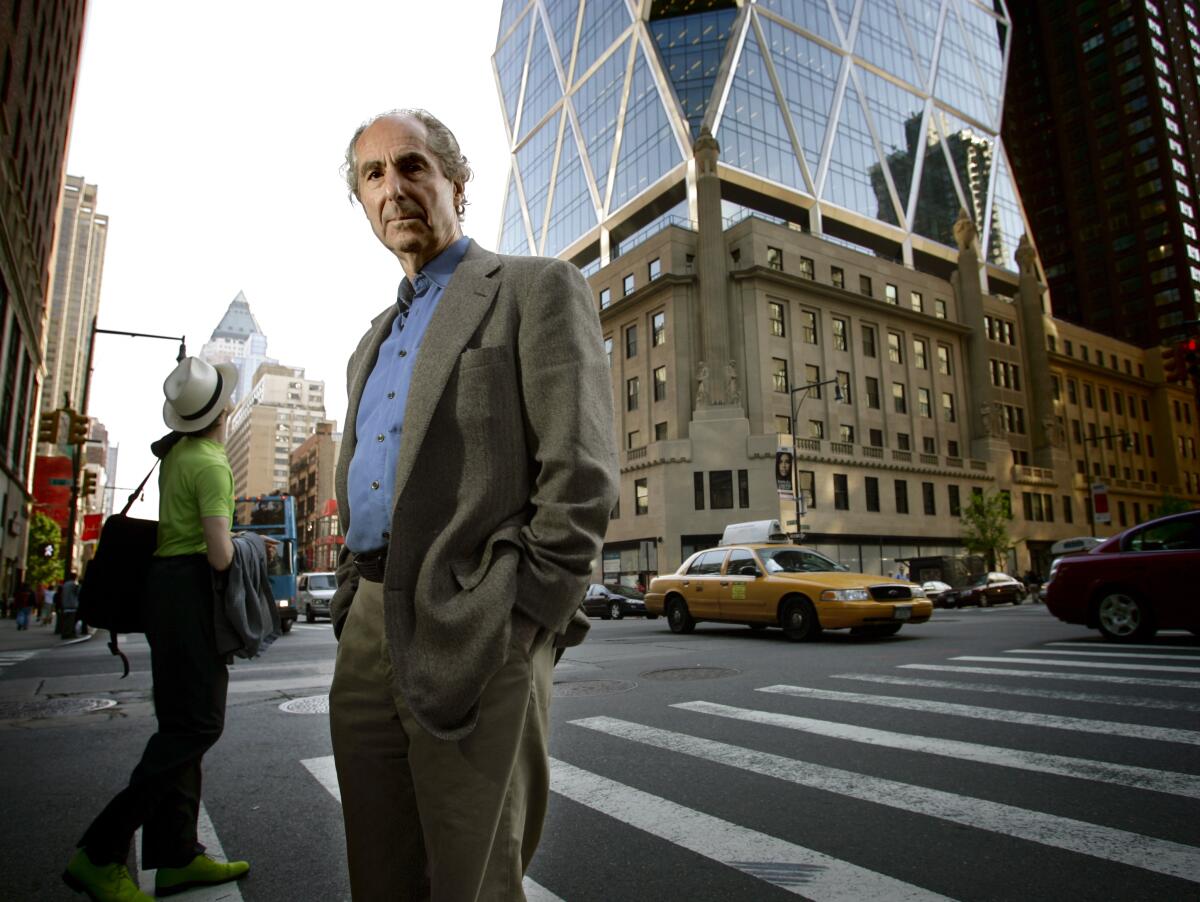

If ‘Philip Roth: The Biography’ leaves you hating its subject, thank Blake Bailey

- Share via

On the Shelf

"Philip Roth: The Biography"

By Blake Bailey

W.W. Norton: 921 pages, $40

If you buy books linked on our site, The Times may earn a commission from Bookshop.org, whose fees support independent bookstores.

How is it possible a writer of Philip Roth’s stature could live through his slice of American history —Depression, World War II, the Cold War, the ’60s; 30 years of widely-distributed growth followed by the slide into dog-eat-dog neoliberalism – and yet the first major biography of the man reduces us to litigating one he said, she said after another?

Here is Roth, humble son of New Jersey, carrier of the legacy of Flaubert and James, author of 31 books, giant of American letters, winner of the Pulitzer Prize and two National Book Awards — and yet he himself, before he died in 2018, worried his biography might end up “The Story of My Penis.”

As a pampered celebrity, Roth preferred his sex with a minimum of commitment. OK — but as a semi-monkish man of routine, what he wanted was domesticity without encumbrance. He cherished privacy and the time to write and then, to break the monotony, some sexual adventuring. Accordingly, Roth expected his girlfriends to act like wives and his wives to act like girlfriends.

It surprised him when women didn’t treat this like a bargain. Once the fun was over, they became (so he indicated) harridans, millstones, neurasthenic bores. Above all, they became unreliable narrators. Blake Bailey has been accused of taking the he said side in “Philip Roth: The Biography,” and it’s true: On a case-by-case basis, the biographer’s thumb often lands on Roth’s side of the scale. The fact that Bailey was personally selected by Roth after a previous biographer proved too unsympathetic has been greeted, justifiably, with suspicion. But I began to suspect he was up to something slier in the course of this 800-plus-page doorstopper.

Bailey is the author of well-regarded biographies of John Cheever and Richard Yates, and he strikes me as neither a hatchet man nor a patsy. It is thanks only to Bailey, for example, that I know Alfred Kazin, the great literary critic, found Roth an insufferable bore. (Kazin said he was “always glad to see him depart in all his prosperity and self-satisfaction.”) Or that Nicole Kidman, after getting a taste of the great Lothario, told him through a friend “to grow up.” Or that Roth bought back his second wife’s badly abused affections with a $3,000 bauble (a “serpent ring with an emerald head and diamond tail”) that he’d tucked under her pillow.

Blake Bailey has written on John Cheever, Charles Jackson and Richard Yates. “Philip Roth: A Life” is his most memorable and controversial biography.

It’s only thanks to Bailey that I know Roth once said of his favorite exes: “I did not marry them because none was a finagler, a cheat, or a manipulator made tenacious by panic who would have her man no matter what.” Or that when one of the jilted dared question whether Roth ever loved her, he responded:

“You didn’t know I loved you when I said I wanted to give you a hundred thousand dollars to get you out of your tight financial straits? You didn’t know I loved you when I watched you trying on clothes at Assets and at Searles? You didn’t know I loved you when I got you a car?”

It is only thanks to Bailey, in other words, that I closed this book and wondered how long it would take to get the rotten flavor of this man out of my mouth.

Whether you despise Philip Roth or not, it’s a matter of more than idle curiosity, I think, how a fiction animated by that exquisitely tuned voice is inseparable from a man who felt he owed the world nothing.

Roth was born two weeks into President Franklin D. Roosevelt’s first 100 days, just as a small cadre of Harvard-educated lawyers, led by Felix Frankfurter, consciously regulated capital virtually out of existence, thus deposing Wall Street from the driver’s seat of the global economy. Young Philip, unbeknownst to him, had been handed a new kind of country to grow up in. America, going forward, was not banker rich, not oligarch rich, but middle class rich. His happy childhood was perfectly timed to be mistaken for ordinary.

Roth was also born seven weeks after Hitler was named chancellor of Germany. “Anti-Semitic demagoguery flourished during the thirties,” Bailey reminds us, and what was demagogued, often, was Roosevelt himself, who’d appointed several Jewish advisors, Frankfurter among them, and whose New Deal was vilified by bigots as the “Jew Deal.” As Bailey points out, a 5-year-old Roth was almost certainly made aware of Kristallnacht. Thus the author grew up in a Normal Rockwell painting, but with Father Coughlin just out of frame, raving.

Utterly at home, always on notice — this dialectic became Roth’s most prized literary possession. A lot was riding on his easygoing, hard won, fluid-edgy voice. In the postwar decades, the first-person “I” was both an author’s highly distinctive ego and a proxy for a middle class no longer in competition with the capitalist toffs. Salinger, Lowell, Hardwick, Berryman, Mailer, Updike, Plath, Sexton, Vonnegut, Bellow — “confessional” is the wrong word here. The challenge was not to expose a hidden thing, but to ask: Who am I that I get to be the hero (or the villain) of my own story?

Tender and slight, deceptively unambitious and in its quiet way perfect, Roth’s first book, “Goodbye, Columbus,” is about an essentially good kid discovering the wages of love and social class. For all its understated charms, it landed, for many readers, like a bulletin from another planet. That the Jewish suburbs were no different from their WASP counterparts came as a surprise to much of Gentile America. They too belong to country clubs! Affluence is making us one people! But to certain readers, the ideal of e pluribus unum cut the other way.

On the anniversary of the birth of the Works Progress Administration, it’s worth asking what a post-COVID Federal Writers Project might look like.

Depicting his characters not as martyrs or folk curiosities but as ordinary Americans was regarded as traitorous by some of his elders. Roth, they felt, had failed to carry the memory of Jewish suffering into his fiction. For this he was labeled an anti-Semite and a self-hating Jew and, incredibly, compared to Goebbels and Streicher. “Goodbye, Columbus” won the National Book Award, at which point its young author was definitively launched. (“At twenty-six,” wrote Saul Bellow, his great hero, “he is skillful, witty and energetic and performs like a virtuoso.”) Even as he ascended, the weight of ancestral sacrifice was being forced onto his shoulders.

Marrying Maggie Martinson was an almost clichéd act of rebellion. She was, Roth believed, a bearer of “goyim chaos,” a promising grad student turned sandwich bar waitress for whom everything had gone wrong. Daughter of a volatile drunk, ex-wife of a vicious no-account, mother of two kids she seemed uninterested in parenting — I began to think that Roth married her not foolishly but with a kind of Jamesian cunning. In the failings of those nearest us, we seek permission to become our worst selves. In Maggie, Roth found an excuse to slip off the yoke forever.

The yoke of what? As Bailey writes, more than just a middle-class decency, “but an eons-long tradition of menschlichkeit,” a degree of common humanness. After Maggie, he’d never again feel obliged to do the virtuous thing. What better way to flaunt this realization than to write an entire novel about masturbation? “Portnoy’s Complaint” became the biggest seller in the history of Random House; it turned Roth from a literary wunderkind into a household name. And it made him very, very rich. Having killed off the kernel of sweetness at the heart of the young man who’d written “Goodbye, Columbus,” he was free to explore the writer not just as egoist, but as stag-on-the-make, as bachelor-king.

His talent carried him up and into the “egosphere” (his coinage), into a world of prize money, A-list parties, touch football on the Vineyard in the dying leaves. For all his attainments, though, Roth remained forever a younger sibling; the family darling with an underwear drawer so beautifully arrayed his mother led her mah-jongg group on a tour of it. The media trained us to wonder annually why he didn’t win the Nobel Prize, even though the snub put him in the company of Tolstoy, Proust, Borges, Nabokov, Joyce and Woolf. Childhood was paradise; my parents gave me everything; the universe owes me accordingly: To such a person, being misperceived is a special kind of terror.

Author Philip Roth, who tackled self-perception, sexual freedom, his own Jewish identity and the conflict between modern and traditional morals through novels that he once described as “hypothetical autobiographies,” has died.

“You wouldn’t be interviewing me if it weren’t for Charles Cummings,” Roth tells his biographer in a rare moment of insight and humility. Cummings is the librarian who assisted him in researching his chef d’oeuvre, 1997’s “American Pastoral.” Roth knew he’d written, at last, a virtuous book, one that secured his claim on posterity. In trying to control Bailey, though, he overplayed his hand. Even as Bailey gave Roth every opportunity to answer his critics, he has also put as much into the public record about the man as 800 pages can accommodate. For the foreseeable future, every work of criticism on Roth will be reliant on these efforts.

When Bailey confronts Roth about one especially appalling episode, Roth feints, denies, quibbles, before concluding: “Hate me for what I am, not for what I’m not.”

Will do.

Metcalf is the co-host of Slate’s “Culture Gabfest” podcast and is writing a book about the 1980s.

More to Read

Sign up for our Book Club newsletter

Get the latest news, events and more from the Los Angeles Times Book Club, and help us get L.A. reading and talking.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.