- Share via

During a video meeting in February, Joshua Wolf Shenk — then the executive director of the Black Mountain Institute and editor in chief of the Believer magazine — showed his genitals to about a dozen colleagues.

The incident was reported to the Office of Equal Employment and Title IX at the University of Nevada, Las Vegas, which houses the literary institute, and Shenk resigned in March. He apologized for what he said was an isolated mistake, explaining later he had been bathing in Epsom salts to alleviate nerve pain.

Interviews with more than 20 people, including current and former staff and graduate students, reveal that the incident was just the latest controversy for the highly regarded literary figure, whose rocky tenure began shortly after he arrived on campus in 2015. Many of those interviewed asked for anonymity, usually for fear of professional repercussions in a close-knit world and in a university that has discouraged public comment.

On at least four occasions, female staff members and students complained to faculty or administrators about touching, inappropriate comments or repeated dinner propositions. At least three others complained about a toxic atmosphere or requests that fell outside their duties. Some claim the university dismissed or failed to address their concerns.

UNLV replied to multiple emails from The Times by saying it “does not comment on personnel matters.”

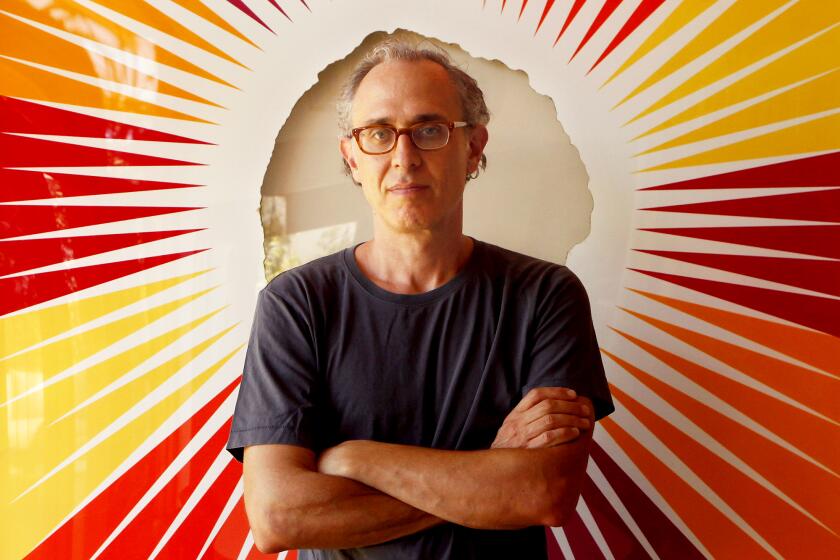

Shenk, the author of ‘Powers of Two,’ resigned as the leader of the Believer magazine and the Black Mountain Institute after a video incident.

“The reason this incident, even if it was unintentional, was so harmful to staff is because Josh had built this environment … of being an inappropriately casual, personal guy,” said one witness to the video exposure, who worked with Shenk. “It was absolutely part of a pattern of behavior.”

Some Shenk supporters contacted The Times to advance an opposing perspective: He was hard-driving but socially awkward — the result, his therapist said, of his being on the autism spectrum. Shenk, speaking with The Times, denied that he had engaged in unwanted contact or propositions and ascribed other allegations to ugly office politics. He said he was hired to reinvent BMI, and he suggested that his critics were entrenched employees who opposed his vision for it.

From the early months of his leadership, when concerns first arose, until the video incident, Shenk continued to operate BMI despite complaints about his behavior. He looked to be fulfilling his mandate — making UNLV a national literary center, an important Western rival to East Coast institutions. But five years later its well-funded institute and major magazine are without permanent leadership, while the university is unable or unwilling to account fully for why one of its most ambitious projects has floundered so visibly.

It was only in May that one UNLV official acknowledged accountability — albeit indirectly. The English Department, which partners with BMI, admitted to shortcomings in addressing harassment and discrimination in an email reviewed by The Times.

“All members of the English Department and UNLV have the right to work and study in a professional environment that affirms their identity and allows them to grow as professionals without fear of mental, emotional, physical, or sexual harm,” said a statement by Gary Totten, UNLV’s English Department chair. “We acknowledge that our university, and our department, have not always lived up to this ideal, and at times it has been a place where people feel unworthy, unwelcomed, or unsafe. We commit to doing better... .”

Though the letter was written partly in response to the video incident, it does not include Shenk’s name.

Current and former employees of ICM Partners allege that the talent agency tolerated harassment and misconduct toward women and people of color.

A rocky start

BMI was launched with a modest budget in 2006 at UNLV, a university best known for its athletics and hospitality programs, as a local institution with a global outlook — establishing fellowships for MFA recipients, launching a student magazine and hosting prestigious speakers such as Toni Morrison and Wole Soyinka.

Between 2013 and 2015, the Rogers Foundation gifted BMI $30 million, one of the largest donations UNLV has ever received. Its headquarters were renovated and renamed the Beverly Rogers Literature and Law Building. It was in the service of a grander mission: expanding the institute — and the desert city surrounding it — into a world-class literary hub. Around that time Carol C. Harter, the founding executive director of what is now known as the Beverly Rogers, Carol C. Harter Black Mountain Institute, began making plans to retire.

UNLV embarked on a search for a successor whose experience, scope and ambition would elevate BMI. A 2013 posting listed among the job requirements “extensive fund-raising experience” and “an established reputation in literature and/or the humanities.”

After a two-year search, they found Joshua Wolf Shenk, an acclaimed author and founding adviser to the Moth storytelling series. He had some executive experience, having led the Rose O’Neill Literary House at Washington College in Maryland — but perhaps more importantly, he had many friends and colleagues in the national literary and media establishment. His energy, ideas and networks were exciting for an institution looking to amplify its cultural force.

Shenk told the Las Vegas Review-Journal he came to the institute to “put Las Vegas on the cultural map,” and he proceeded to do so. He acquired and edited the Believer magazine, a Bay Area journal on par with any Eastern literary publication, and launched the Believer Festival in Las Vegas.

“Publishers had been reticent to send authors to Vegas because books never sold,” Scott Seeley, co-owner of downtown Vegas’ The Writer’s Block bookstore, told the New York Times in 2019. “The Believer coming here legitimized this city in the eyes of the machine out there.”

But inside the Rogers building, clashes and concerns arose. Some former colleagues alleged that Shenk disparaged colleagues, made unrealistic demands or treated those beneath him as obstacles to his success.

“He belittled the staff and was condescending to faculty and graduate students,” wrote Joseph Langdon, who had been a BMI assistant director at the time, in a statement published this spring on Medium. “He did not tolerate opposing views.”

A spokesperson for Shenk said the assertion that he stanched opposing views “is 180 degrees from the truth.”

Shenk had hired an executive coach, Joanne Heyman, and she joined BMI as a strategic adviser. Shenk told his staff in an email that Heyman came on to “get to know you, your values, and your strengths, so she can better advise me on management and help us grow as a team.”

During an October 2015 BMI retreat, Heyman interviewed staff — some of whom raised concerns about their new boss — and crafted a report on how best to align Shenk’s goals with their expectations. Langdon and another person familiar with the report said it did not capture the scope of their concerns.

“I remember being shocked by [the report],” said a UNLV faculty member familiar with it. “The sense I had was that ‘OK, everything is good. And anyone who doesn’t support Josh can consider resigning.’”

“I remember being shocked by [the report]. The sense I had was that ‘OK, everything is good. And anyone who doesn’t support Josh can consider resigning.’”

— A UNLV faculty member.

Heyman said she was not at liberty to provide a copy of the report. Shenk said he couldn’t find one and UNLV said there were “no records responsive” to a Times request for the report.

In an interview, Heyman said she did document staff concerns, though she declined to provide specifics.

“My report outlined some various areas of conflict, including around Joshua’s role and responsibilities,” she said. “It also touched on concerns that staff raised that he might be moving too quickly.”

In a conversation with The Times, Shenk emphasized “that there were zero concerns raised about misconduct or anything inappropriate” during the retreat. “It was simply a mundane workplace disagreement.”

Langdon, the BMI assistant director, wanted to serve “the ivory tower,” Shenk said, while “my vision was ‘Let’s go out into Las Vegas, which is one of the most neglected communities in North America by arts institutions, and tie it up with the national literary scene.’”

Langdon alleged that Christopher Hudgins, UNLV’s then-dean of the College of Liberal Arts, accepted Heyman’s report without question and used it to “threaten the staff with termination.”

Hudgins did not respond to requests for comment.

Within two years of Shenk’s hiring, four of BMI’s five staff members had left. “Things fell apart,” said the UNLV faculty member.

Asked about the criticism of his leadership, Shenk responded, “Conflicts arise in any workplace, and I did my best to manage them in a professional and transparent way.”

Some who worked with Shenk agreed. “Josh was awkward, eccentric, overpaid, ambitious and he changed how BMI ran,” said a former BMI fellow who asked to remain anonymous. “These things made him unpopular with some BMI staffers who preferred the old way of doing business under the previous director. Then his disastrous, inexcusable Zoom call happened and these workplace grudges took on a new life.”

“Josh was awkward, eccentric, overpaid, ambitious, and he changed how BMI ran. These things made him unpopular with some BMI staffers ... Then his disastrous, inexcusable Zoom call happened and these workplace grudges took on a new life.”

— A former BMI fellow who asked to remain anonymous.

Complaints about Shenk’s leadership preceded his arrival in Las Vegas.

Kathryn Bursick, a former assistant at Washington College’s Rose O’Neill Literary House, where Shenk was director from 2006 to 2009, alleged that Shenk was verbally abusive. Bursick recalled a time when the associate director asked Shenk not to yell at her — to which he responded that “he didn’t want to work where he couldn’t express his feelings.”

The associate director, who asked for anonymity, confirmed the exchange. She alleged that Shenk was “erratic. He would go from telling me he wanted to give me a raise to telling me I was on probation within the week.”

Shenk’s spokesperson said the associate director “was struggling to perform her job, in a case being managed by college HR.”

Bursick said she shared her concerns about Shenk with Christopher Ames, then a college provost and dean. “My concerns I recall largely being dismissed or waved aside,” she said.

Ames declined to comment.

Two former students at Washington College said in separate interviews that they felt uncomfortable around Shenk. “He had no sense of personal space,” said Emma Sovich, one of the students; she recalled being backed into corners. It didn’t feel intentional or sexual, she said, but it “unsettled” her.

Some of Shenk’s supporters said he was intense and socially awkward, but they did not feel any discomfort. (Several BMI alumni also reported only positive experiences with Shenk.) They said framing awkward body language as misconduct would not only be unfair to Shenk but might risk chastising the kind of unconventional behavior he has worked to destigmatize.

“His whole career has been spent destigmatizing mental health and physical pain and oddness and looking at their intersections with creativity and authenticity,” said the writer Bliss Broyard, Shenk’s friend and former colleague at the Moth. Shenk’s books include “Lincoln’s Melancholy: How Depression Challenged a President and Fueled His Greatness.”

A clinical psychologist who is treating Shenk, who spoke with his permission but asked not to be named because of the confidential nature of their relationship, ascribed Shenk’s interpersonal mishaps to “significant mental and physical health challenges,” which include bipolar disorder, complex trauma, fibromyalgia and autism spectrum disorder. He said Shenk’s conditions can make it difficult for him “to read and understand another’s experience.”

Jennifer Senior, a staff writer at The Atlantic, has been Shenk’s friend for nearly 30 years. “[I]t is inconceivable to me that Josh Shenk walks around in this world with a will to do harm,” she said. “He is motivated by its opposite: A will to understand pain and suffering, two conditions with which he is all too familiar.”

“Was the guy socially awkward? Yes,” said a former UNLV teacher, who asked to remain anonymous for fear of professional fallout. “Neurodiverse? Probably. Was he a predator? No way.”

Under Shenk’s leadership, the former teacher added, “BMI revolutionized literary programming in Las Vegas, but it rubbed some people the wrong way.”

More complaints arise

In 2016, Shenk invited a female colleague out to lunch “to get to know me,” she recalled. At the time, she held an interim position in a UNLV department that often hosted BMI events.

He was casual and intimate from the start. When they arrived at a Hard Rock Cafe, he sank into his seat and said, “I’m just so depressed,” recalled the woman, who is now an executive faculty member and asked to remain anonymous.

BMI sometimes hosted events inside the space the woman ran; operating them required frequent coordination with Shenk. She accepted one of his dinner invitations, she said; another time he joined her for dinner after an event. But even after she declined, he continued to ask her to dinner — totaling more than 10 invitations, she said.

Shenk would sometimes put his arm around her, and once touched a mole on her neck, she recalled.

Then, she alleged, during a 2018 event at UNLV, Shenk stood behind her, pressed his belly against her back and massaged her shoulders. She picked up his hands and threw them down, she recalled. Two attendees confirmed witnessing the incident.

Shenk’s spokesperson denied the allegations of physical contact, adding that Shenk “deeply respects this colleague and is pained by what he can only imagine is a terrible misunderstanding.” He said Shenk “was unaware that any colleague was upset by any of his invitations.”

The woman reported the incident to UNLV’s Office of Compliance. An email from the office, which The Times obtained, informed her that Shenk was reminded of “the expectation of maintaining appropriate, professional boundaries with students, fellows, and staff” and “cautioned that future allegations of a similar nature could lead to a formal investigation.” Her concerns had been shared with the dean’s office, the email said, and “at this time, no further action will be taken.”

Shenk said the report he received from the office did not mention physical contact. “He wasn’t informed about this allegation of contact; had he been, he would have denied it,” his spokesperson said.

Shenk’s behavior improved after the woman reported the incident, she said. Nevertheless, “What he did with me was creepy and horrible and contributed to much anxiety.”

“He made me feel like I had to be really personal with him in order to get any opportunities… I chose not to work with BMI specifically because of what happened with Josh.”

— Al Hastings, a former MFA student.

It was not the first or the last complaint made to the university.

Al Hastings, who uses they/them pronouns, first met Shenk in 2016 as a first-year MFA student. At an event Shenk hosted in his home, he put his arm around Hastings’ shoulder and began asking “really personal questions” about their family and their partner, Hastings said. Shenk offered to give Hastings a tour of his home. When he took them into his bedroom, Hastings quickly left. (Zachary Wilson, Hastings’ friend, remembered them leaving the party early.)

“That was a major moment for me,” Hastings said. “He made me feel like I had to be really personal with him in order to get any opportunities. … I chose not to work with BMI specifically because of what happened with Josh.”

Shenk responded that his home was a “vintage Vegas place” and he was often asked for tours. “If gesturing to one of my bedrooms caused discomfort, I regret it.”

Hastings told two UNLV professors about their uncomfortable encounters. They said the professors warned them that Shenk sometimes made women uncomfortable and told them to take precautions. (One of the professors confirmed giving Hastings advice about a complaint.)

Shenk denied dealing inappropriately with the student. His spokesperson said while Shenk did not supervise graduate students, he was “responsive to any queries or requests” and “careful not to show favoritism.”

In April 2017, Zoë Ruiz sent Shenk an email. A contract worker for BMI and the Believer at the time, she complained that Shenk had called her a “puppy dog” in front of another female colleague. Shenk apologized for the remark in an email the following day.

But that was not Ruiz’s only allegation. She also wrote that during the Believer Festival, which she coordinated, three women told her Shenk stood too close and was “too touchy.”

Shenk apologized and responded: “I’m sure you can understand that it’s hard for me to respond to secondhand reports, though I certainly don’t expect any more detail from you. I find these suggestions distressing, because I don’t want anyone to ever feel uncomfortable around me.”

That same year, Lorinda Toledo, a UNLV PhD student and BMI fellow, told a faculty member about Shenk’s “strange” handshakes. He would approach her with an extended pinky or pointer finger and wouldn’t put it down until she gave him a pinky handshake or touched his pointer finger with hers.

Toledo took her complaint to Douglas Unger, professor and co-founder of UNLV’s Creative Writing International Program. Unger confirmed the complaint and told The Times that another female student had spoken to him about Shenk, leading to a meeting with Shenk about “putting a buffer between him and the students.”

Shenk said he does not recall that conversation. The handshakes, Toledo said, soon stopped.

Unger brought up these concerns with three successive Liberal Arts deans, he said — Hudgins, Chris Heavey and current dean Jennifer Keene. “Every time, the message to me and other faculty was, ‘You must try to get along with Black Mountain Institute,’” he said.

In an interview, Shenk said Unger — a “writer of fiction” and a “teller of fictions” — had been critical of BMI for years. “It’s true he and I were in meetings with deans a lot, not with him complaining about my behavior but with me and the deans trying to work it out with him because he was such a difficult figure.”

Hudgins and Heavey did not respond to requests for comment. Keene referred The Times to UNLV’s media relations office, which declined to comment.

Some accommodations were made, according to Unger and another person familiar with the situation: On at least two occasions, space was made for students on the second floor of the Rogers building — which houses the English Department — in part so that they didn’t have to work on the first floor, where BMI is located.

Shenk said the moves were mundane reallocations of space.

Otherwise, an uneasy stalemate took hold: Complaints were made and tensions were allowed to build. Students were not informed of any medical issues that might explain Shenk’s behavior.

“None of us were there to be able to react or to take action in response to many issues, though many of us tried,” Unger said. As another UNLV faculty member put it, Shenk “inherited a lot of that good will” from Carol Harter, who ran BMI somewhat independently. The result, they said, was a gap in oversight, “and that gap made a lot of his behavior possible.”

That seemed to change after the video incident. Shenk resigned nearly seven weeks later.

UNLV appointed John P. Tuman, an associate dean in the College of Liberal Arts whose field is political science, as acting executive director of BMI. Daniel Gumbiner, the Believer’s current managing editor, is overseeing the magazine’s day-to-day operations, UNLV said. The university says the search for a permanent director is ongoing.

More to Read

Updates

3:16 p.m. Aug. 18, 2021: This story has been updated with a response from Shenk.

Sign up for our Book Club newsletter

Get the latest news, events and more from the Los Angeles Times Book Club, and help us get L.A. reading and talking.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.