Review: Objects and ideas come to life in Ruth Ozeki’s mad, floating literary world

- Share via

On the Shelf

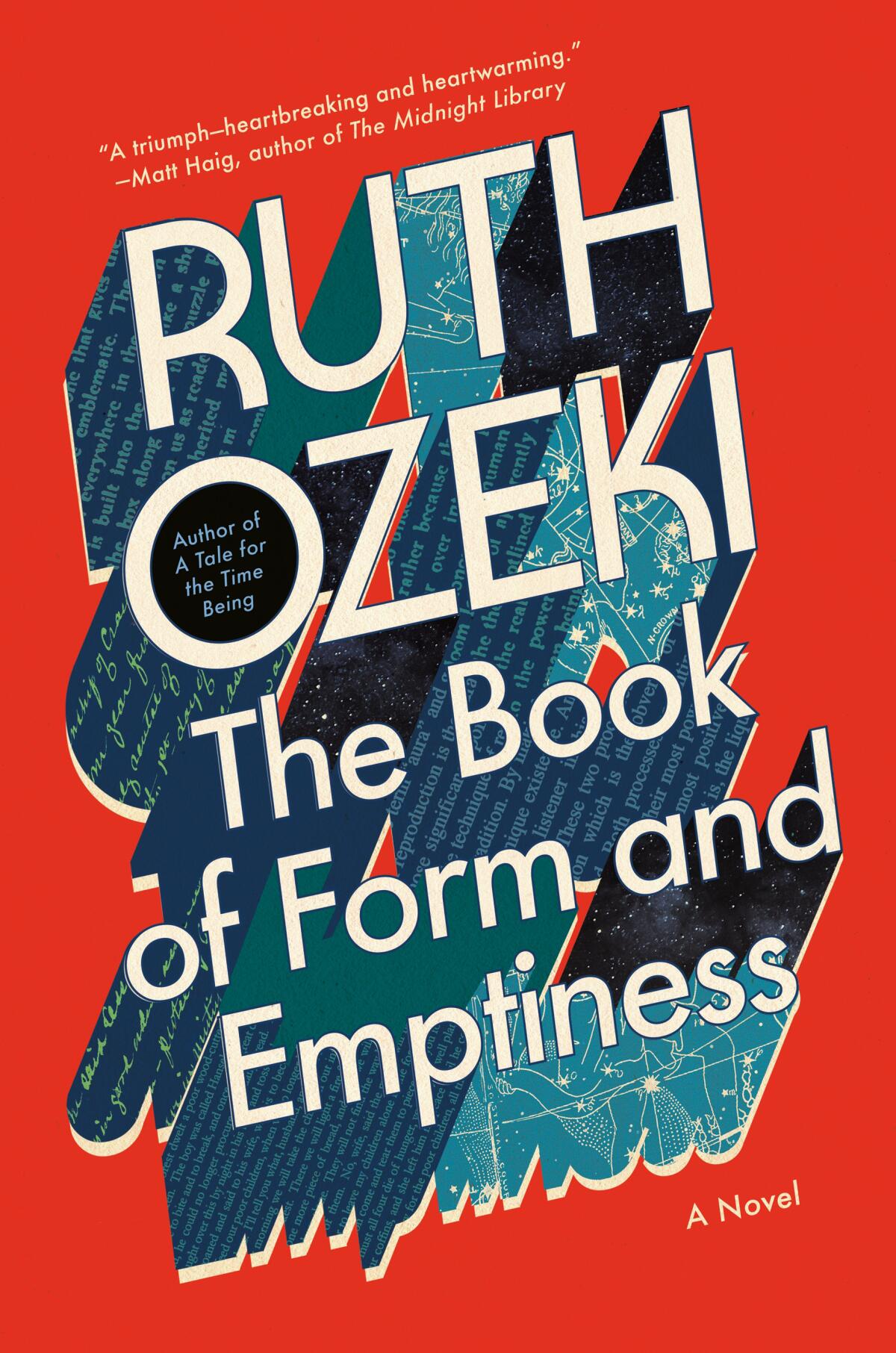

The Book of Form and Emptiness

By Ruth Ozeki

Viking: 560 pages, $30

If you buy books linked on our site, The Times may earn a commission from Bookshop.org, whose fees support independent bookstores.

We live in an age dominated by our possessions. Capitalism, the internet and Amazon have ensured we can have anything we desire (and can afford). What if all our acquisitions, effortlessly acquired, started talking back to us, their voices crowding our heads as their presence clutters our lives?

This startling notion animates Ruth Ozeki’s new novel, “The Book of Form and Emptiness,” a vivid story of fraught adolescence, big ideas and humanity’s tenuous hold on a suffering planet. Ozeki, a Zen Buddhist priest, Smith College professor and the author of 2013’s Booker-shortlisted “A Tale for the Time Being,” tells the story of Benny Oh, a teenager whose father, a caring and lighthearted jazz musician, is run over by a garbage truck.

In his grief, Benny starts hearing voices from inanimate objects. His mother, Annabelle, grappling with her own sorrow, tries and fails to help as Benny cycles through despair, anger and the pains of growing up.

Though mother and son drive the narrative, Ozeki’s stage overflows with a large cast of both characters and sentient objects. Benny joins a troupe of Neil Gaiman-esque outcasts who swill vodka, shoot heroin and revere the words of the philosopher Walter Benjamin. Annabelle corresponds with the Japanese author of a book with a distinct resemblance to Marie Kondo‘s “The Life-Changing Magic of Tidying Up.” And “The Book,” the very one in the reader’s hands, is a sentient being who writes Benny’s story, which Benny grouchily corrects along the way. In the deep core of this fable is a disused bindery in a public library, a relic of an age when books were treasured objects, its ghosts channeling the author’s thoughts on literature, the riddle of existence and the universe.

Benny’s world falls apart and then reconfigures in a fractured pattern. He develops “supernatural ears” for the voices of everyday things. Like a Disney movie on acid, teapots and cutlery begin to murmur, scream and dictate to him; a beloved antique spoon laments its many losses. For Benny, sorting what is real becomes a huge challenge and a philosophical question, an onerous burden for a 14-year-old. Observing a fellow bus rider talking to the air, he thinks, “The old crazies must have been young once, too. Maybe he was turning into one.”

Sally Rooney, Anthony Doerr, Maggie Nelson, Richard Powers, Jonathan Franzen — the list goes on. Four critics on kicking off a big, bookish fall.

His only place of respite from the hectoring voices is the library, where “he discovered that when he was reading to himself, all the other voices in his head grew quiet and still, much the way children grow quiet and still during Children’s Hour.” He shares his remote refuge, a forgotten carrel on the 9th floor, with a woman with a distinct resemblance to Ozeki herself.

Benny’s fragile truce with his tormentors falls apart when a pair of scissors orders him to stab his teacher. Benny turns the blades on himself instead and winds up on a psychiatric ward in the care of Dr. Melanie, one of literature’s most annoying therapists. (Ozeki spent time on a psychiatric ward as a teenager.)

Annabelle, meanwhile, navigates her own crises. Her painful and cockeyed attempts to help Benny will resonate with anyone who ever parented a teenager. Her job monitoring the news for a media company is a daily plunge into the worst of current events: school shootings, rampant viruses, the poisonous presidential campaign of 2016. Only buying stuff makes her feel better, and as her apartment fills with stuffed animals, old newspapers, unwashed dishes and broken crockery, eviction seems imminent.

Benny’s precarious flights toward freedom and refuge drive the plot, as does young love; on the ward, he meets the Aleph, a mysterious young runaway with her own problems. As the action moves from America to Japan and back, the “Tidy Magic” author, a Zen Buddhist abbess, fields fan letters from Annabelle and ponders whether and how to help Benny.

Rumaan Alam’s “Leave the World Behind” starts as satire and becomes the anatomy of “normal” life during global disaster — and a dire warning to us all.

By now readers will have surmised that this is a novel of big ideas. Zen Buddhist precepts guide the meditations on our relationships with objects, and at times the narrative threatens to buckle under the weight of its conceptual burdens. Some characters feel flat, marshaled forth to advance a theory rather than embody a real person.

Benny and Annabelle, though, are viscerally real. And Ozeki, an imaginative writer with a subversive sense of humor, has an acute grasp of young people’s contemporary dilemmas.

“All the kids were tired these days,” a nurse on Benny’s ward observes. “They stayed up late, texting and posting on social media and watching videos on YouTube. They stayed indoors playing games online, inhabiting multiple roles in massive multiplayer virtual realities ... hearts pounding, adrenaline pumping, narrowly avoiding permadeath as they tried simply to survive, and this was on top of their afterschool activities, their music lessons and soccer practice. No wonder they were tired.” This would be a great book to read in tandem with an adolescent in your life, a potential classic for the young-adult audience.

“The Book of Form and Emptiness” overflows with love and a lot of sadness too — including the sorrow of the Book, which suffers the abandonment of its readers: “Why did you revere us so? Because you thought we had the power to save you from meaninglessness, from oblivion and even from death, and for a while, we books believed we could save you, too.” Ozeki doesn’t offer anything as complete as salvation but something more real: a profound understanding of the human condition and a gift for turning it into literature.

Gwinn, a Pulitzer Prize-winning journalist who lives in Seattle, writes about books and authors.

In ‘The Morning Star,’ Knausgaard’s first major novel since his semi-fictional ‘My Struggle,’ psychodramas are outshined by a cosmic disturbance.

More to Read

Sign up for our Book Club newsletter

Get the latest news, events and more from the Los Angeles Times Book Club, and help us get L.A. reading and talking.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.