Review: How a SoCal travel writer found beauty in the ugly places

- Share via

On the Shelf

A Salad Only the Devil Would Eat: The Joys of Ugly Nature

By Charles Hood

Heyday: 224 pages, $16

If you buy books linked on our site, The Times may earn a commission from Bookshop.org, whose fees support independent bookstores.

Travel writing seems to reward the young and agile. Have any of Paul Theroux’s recent books felt as ferociously urgent as his first? Later-life collections can find a once-intrepid (or at least tireless) scribe ready instead to ponder a bad knee or worse service at a restaurant, or generally to lament what once was or could have been.

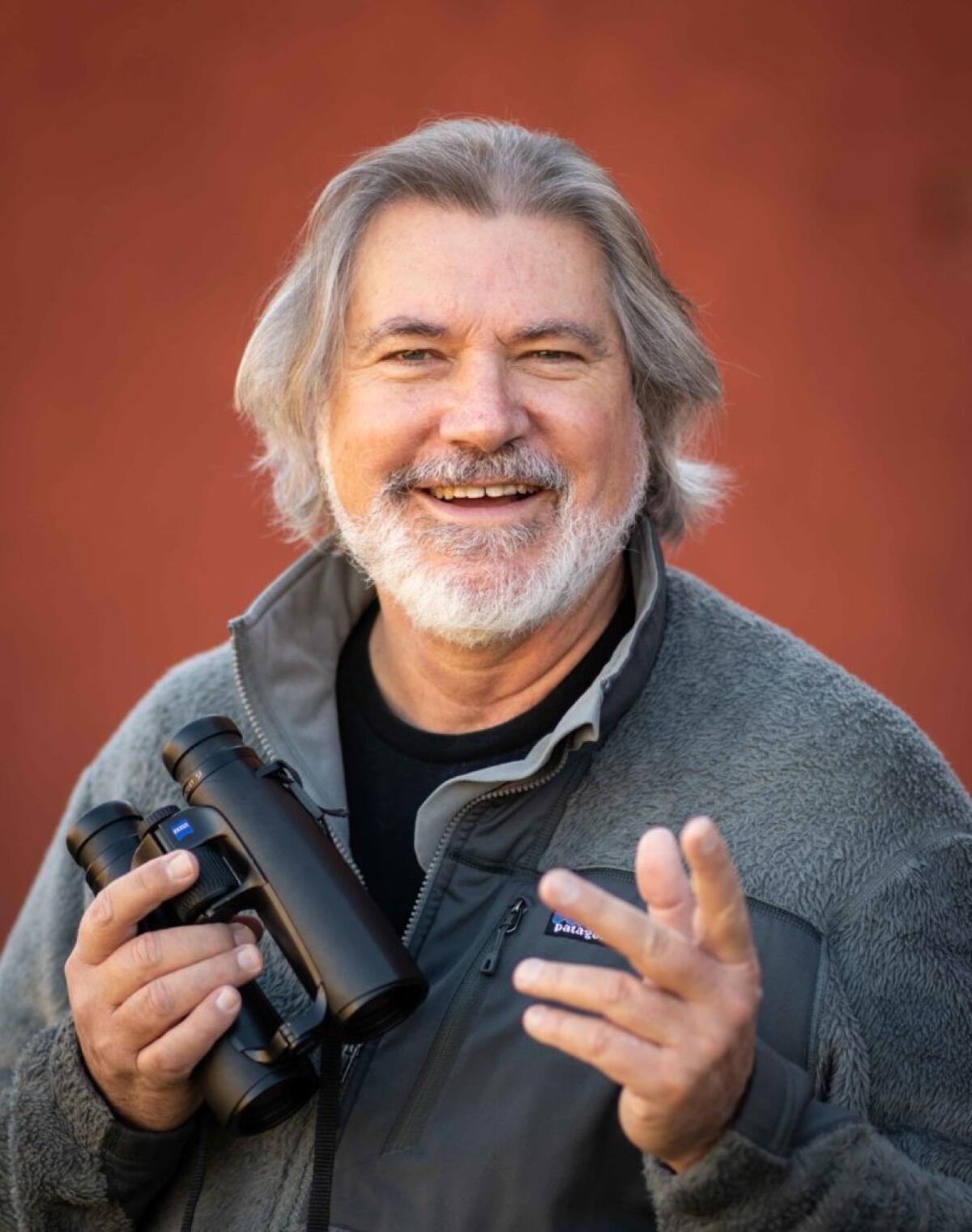

Charles Hood, a Southern California writer now into his 60s, certainly has regrets. There’s his original decision to major in English long ago, a divorce of more recent vintage, choices he made as a father or teacher. But from these difficulties emerges the fascinating core insight of his new collection, “A Salad Only the Devil Would Eat”: that what appears to be ugly or awful can, with the right knowledge and context, be seen instead as unique, even gorgeous.

The opening essay, “I Heart Ugly Art,” describes a job Hood applied for in the late 1980s, teaching writing at a college in the Antelope Valley. “I drove Highway 14 back to Lancaster, had lunch, then changed into my suit in the restaurant parking lot,” he writes. “I took out my earring and put on my wedding ring. I pushed my fingers through my hair. Show time.” What they are looking for, it turns out, is a lifetime commitment to teaching remedial English. A would-be supervisor asks: “Had I taken the wrong exit? Did I even know where I was?”

“I Love You but I’ve Chosen Darkness” is a novel torn from Watkins’ desert life — Charles Manson, addiction and the incessant pursuit of true freedom.

A committed birder, poet, writer, world traveler, but most of all someone who delights in scrounging beauty from an unloved parking lot, Hood tells the committee the truth: that he knows exactly where he is. That in fact his next stop is “the sewage ponds” across town, where he is after a certain species, Franklin’s gull, named after Sir John Franklin, a polar explorer who died of scurvy in 1847. “According to campus legend,” he notes wryly, “I ended by standing on the table, flapping my elbows and imitating bird calls.” Naturally, he got the job.

Hood’s essays often succeed on the strength of such humor and specificity, born of decades of hard work as a thinker and wanderer in search of things small and beautiful and often beaked. (He is also co-author of the revelatory guidebook “Wild LA.”) Put it another way: Anyone can tell you Lancaster is more than just a place to get gas on the way to go skiing; Hood will actually persuade you to look more closely at that highway median, at the “yellow static of cheatgrass” that “fills up all the spare pieces of dirt.”

Layered over such prose poetry, in a dozen essays about the desert, the semiurban corners of L.A. County and some of the many nations and oceans Hood continues to explore, is an equally impressive and lightly worn knowledge of ecology and history. Where another naturalist might come off as a showy mansplainer, Hood feels like a cool older friend, sunburned and binocular-strapped, when he tells us California has 17 species of pine and 20-odd oaks: black, island, scrub, Engelmann — ”enough species to make seeing them all a tough job.”

‘Something New Under the Sun,’ Alexandra Kleeman’s astounding second novel, features a child star, an eco-cult and a sinister substance called WAT-R.

Indeed, what makes this collection such a consistent joy is ultimately how hopeful the author feels, and how much he continues to enjoy moving through the world despite the twin realities of bad knees and climate change. “I keep journals to document my self-improvement,” he offers, “even when there is very little good news to report.”

Reading Hood’s work will make you feel smarter but, even more crucially in this dire age, more open to the sublime. It comes in defiant little moments. Hood asks an Indian biologist how many tigers there are in Mumbai, population 13 million. He answers 300. “How did they get there?” Hood follows up. “They were always there.” Other moments of odd beauty include a history of palm trees, those gawdy California transplants that “repeat the lie: you can never be too tall or too thin.” Hood reports that 40 potted palms sank with the Titanic, and that those planted decades ago in L.A. might very well be on the verge of a mass die-off.

According to some studies, anyway. The truth — about the palms and much else — is that we don’t know. Ultimately the book feels like a challenge to be as cheery a traveler as Hood, just as open to finding pleasure in incomplete knowledge and imperfect nature as in tracking down pristine postcard vistas. “Go before the border closes, the crevasse widens, the herd thins, the engine stalls, or the pestilence spreads,” he implores. “Take a friend if you can; go alone if you must.” But at least read this book. It’s a true delight.

Suzanne Simard’s groundbreaking research inspired Richard Powers’ ‘The Overstory.’ Now she’s published her own memoir, ‘Finding the Mother Tree.’

Deuel is the author of “Friday Was the Bomb: Five Years in the Middle East.”

More to Read

Sign up for our Book Club newsletter

Get the latest news, events and more from the Los Angeles Times Book Club, and help us get L.A. reading and talking.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.