Born Black and poor in Stockton, he was mayor by 26. Michael Tubbs’ memoir tells the tale

- Share via

On the Shelf

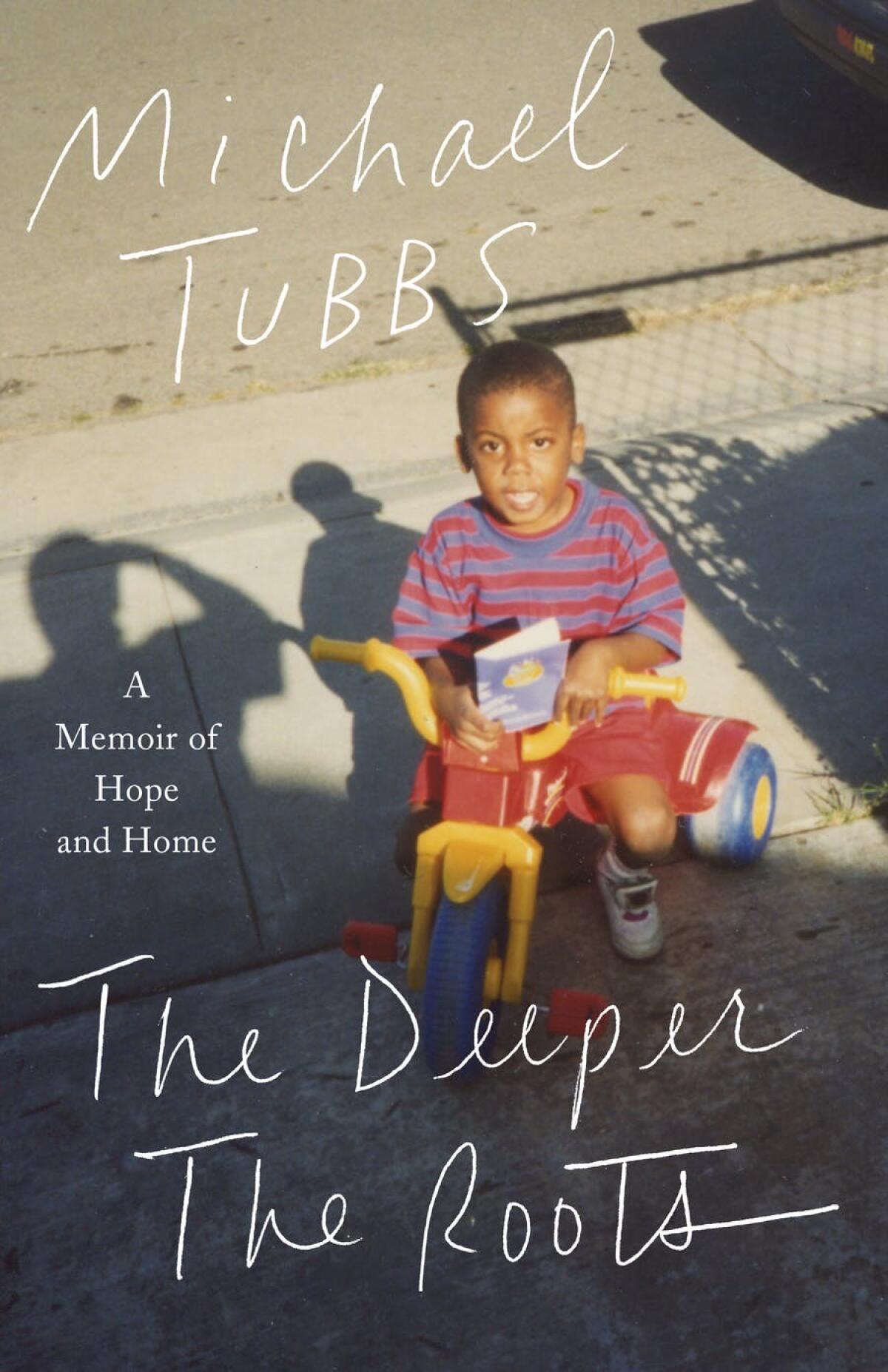

The Deeper the Roots: A Memoir of Hope and Home

By Michael Tubbs

Flatiron, 272 pages, $28

If you buy books linked on our site, The Times may earn a commission from Bookshop.org, whose fees support independent bookstores.

“Did you hear about the rose that grew from a crack in the concrete? Proving nature’s laws wrong, it learned to walk without having feet.”

For most of his life, Michael Tubbs has carried around that verse, from Tupac Shakur’s poem “The Rose that Grew from Concrete,” like a mantra in his head — a reminder to himself of where he came from and why it matters.

When Tubbs was 6, his father was sentenced to at least 32 years in prison for kidnapping, robbery and a drug violation. His mother, Racole Dixon, was 23. She raised him with help from Tubbs’ aunt and grandmother — his “three mothers.” They lived in poverty, and he knew the odds were stacked against him.

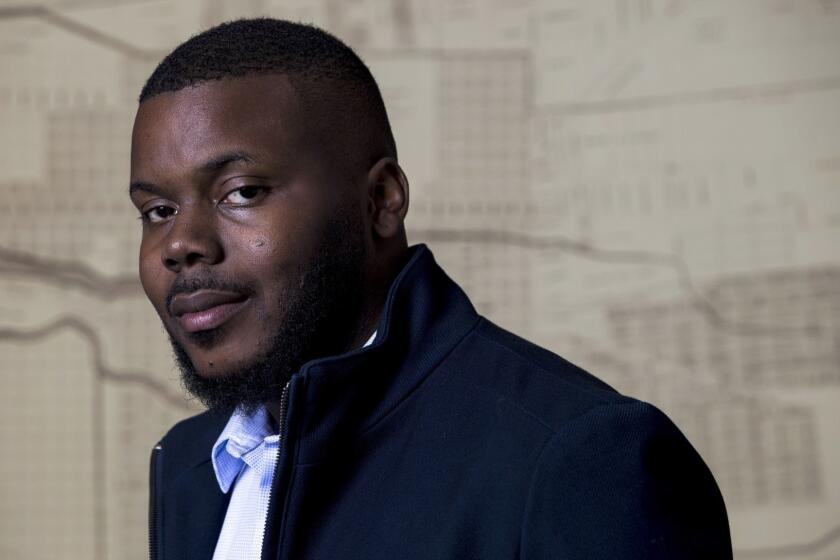

Tubbs’ anger at his circumstances became fuel — it propelled him to excel. He interned at the White House and graduated with honors from Stanford in 2012; at 22 he was elected to the city council of his hometown of Stockton; at 26, he became the city’s first Black mayor and the nation’s youngest.

Tubbs, now all of 31, has achieved more than most would hope to by the end of their lives, and all of it despite — or maybe because of — his origins.

After a surprise defeat for a second term as mayor of Stockton, Michael Tubbs takes his economic agenda to the governor’s office.

“[My moms] were pragmatic visionaries,” Tubbs explains after a recent visit to his office and guest house in Hyde Park, a historically Black neighborhood in South Los Angeles. (He moved to L.A. this year.) “They had a vision of what success could look like… and how to get there, which was to do well in school, which would provide some structure and discipline. But they also provided a lot of love, focus and attention.”

In a new memoir, “The Deeper the Roots,” published by the Flatiron imprint An Oprah Book, Tubbs recounts how, throughout his life, he battled “the soft bigotry of low expectations” — a phrase he intentionally co-opted from a George W. Bush speech. Intimate and insightful, the book is also a love letter to his three moms.

Tubbs’ simple, uncluttered Hyde Park office puts that matriarchal devotion on display. On a table, his memoir sits alongside a book by his wife, activist Anna Malaika Tubbs, that is very on-theme: “The Three Mothers: How the Mothers of Martin Luther King Jr., Malcolm X, and James Baldwin Shaped a Nation.”

On a wall hangs a colorful portrait of Fannie Lou Hamer, the Black sharecropper turned civil rights activist. It reminds him, Tubbs says, “of the genius that’s everywhere.”

Tubbs is friendly and relaxed on our brief office tour, speaking with his hands and exuding the cool confidence of a young man who knows he has nothing left to prove.

Friends and family mourn Anthony Veasna So, whose highly anticipated debut story collection, “Afterparties,” brings refugee Stockton to life.

When a staff member floated the idea of a memoir in 2017, Tubbs, who was mayor at the time, was taken aback. “I’m 26 years old!” he remembers responding. “Write a book about what?” He eventually relented, realizing his story could serve as a source of strength and inspiration to someone else, maybe someone like the boy he was. He wrote a proposal, and after a bidding war sold the book for $150,000 — among the biggest acquisitions by Oprah Winfrey’s eponymous imprint.

After the birth of Michael Malakai, his first child, in October 2019, and Nehemiah in August, the book acquired a more personal meaning: It might help them understand their father — and help him understand his.

“I realized in writing, in thinking about my relationship with my children, that as a kid I always thought that part of my father’s incarceration was that he didn’t care about me, or that it didn’t hurt him to be gone,” Tubbs says. “And I realized it was probably the exact opposite.”

His father, still in prison, hasn’t seen the book yet, and his mother hasn’t brought herself to read it. “It’s hard because it brings back pain and old memories that you want to forget,” Dixon says. “You try to move on from that.” She might listen to the audiobook, though. “I’m still debating.”

Indeed there is both joy and pain in the book, formative experiences inspiring and infuriating. Tubbs writes about winning the Alice Walker Essay Contest in high school and meeting the iconic Pulitzer Prize winner. About the civil complaint he filed with the NAACP against a racist biology teacher, who was subsequently banned from teaching at his high school. About the murder of his cousin Donnell, a tragedy that put him on course for a life of public service.

Jan Barker Alexander, who was an associate dean at Stanford when they met, vividly remembers Tubbs from those years.

“He was a real one,” she says. “He wasn’t pretentious. He understood who he was, that he was a Black man in America and that he did not need to be anything else in the space that he walked.”

She was impressed by his sense of purpose — which was not merely to succeed but to help those who hadn’t. “At his core, he understood that his assignment was to think about the most vulnerable … he never lost focus on who and what was important.”

Amid his successes, Tubbs also writes about the rejections that, he believes, ultimately made him stronger.

“‘Nos’ are such a gift,” he says. “Not the ‘no’ in and of itself, but what you learn from the ‘no.’ It’s such a gift. You’re not always going to get ‘nos.’ You’re not always going to get rejected, just like you’re not always going to get ‘yeses’ or win.”

In a chapter titled “Keys to the City,” he recounts one of the most shameful experiences of his life. On Oct. 18, 2014, Tubbs, then a council member, was bar-hopping with a friend in Sacramento for a double celebration: the grand opening of the Financial Credit Union in South Stockton — thanks in part to his efforts — and news that “True Son,” a documentary about his run for city council, was going to premiere at the Tribeca Film Festival.

Stockton Mayor Michael Tubbs, 30, faces a possible reelection loss to a first-time mayoral candidate after coming under attack from a popular local website run by a man with a grudge against Tubbs.

Rather than crash at his friend’s house, Tubbs drove home at around 3:30 a.m. He was pulled over after failing to signal on the freeway. The Breathalyzer read .137, almost double the limit. “Here I was, fulfilling the grim prophecy I had been told growing up, that I would end up arrested and in jail one day,” he writes.

He feared his career was over, his reputation ruined. Instead, his family, most of his colleagues and his community stood by his side. He’d been given the chance “to atone and try again.”

“At twenty-four years old, my dad and so many like him were not given a second chance,” he writes. “At twenty-four years old, I was ... Ever since then, this guilt has driven me to orient my work to answer the question ‘What if we lived in a society that actually gave people the opportunity for redemption?’”

In this context, Tubbs hopes to redefine the bigotry of low expectations — a phrase often deployed to oppose affirmative action. “You don’t have to lower expectations for folks,” he says. “You just have to give them opportunities.”

Tubbs made the most of his second chance. Two years after his arrest, he was elected mayor of Stockton with more than 70% of votes.

In citywide office, he tacked leftward, expanding opportunities across Stockton’s diverse communities. Tubbs launched the Stockton Economic Empowerment Demonstration project, the country’s first basic-income pilot program; founded the Reinvent Stockton Foundation to administer college scholarships; and brought the Advance Peace program to the city to reduce gun violence.

And then he lost his bid for reelection, a defeat he blames on a “four-year misinformation campaign” — as well as his successful effort to end subsidies for golf courses.

“I just really underestimated the feelings that golf can arouse,” he says. He also learned a lesson about how the messenger can overshadow the message. “A 27-year-old Black guy saying ‘We’re going to stop subsidizing golf’ may not have been the best way to approach” the conversation.

Despite losing in the Stockton mayoral race, Michael Tubbs is expected to keep rising in Democratic politics

Looking back, he jokes, “maybe I should’ve left that golf course alone. But if I did that — it’s like a butterfly effect — I would still be mayor, which was a great job, but I’m so happy not to be mayor right now.”

Tubbs is enjoying a quieter life these days. In March, he moved with his family to L.A. after accepting a job offer from Gov. Gavin Newsom. In his unpaid role, Tubbs is serving as a special advisor for economic mobility and opportunity. (He pays the bills with income from the book, speaking gigs, a Rosenberg Foundation fellowship and his chairmanship of Mayors for a Guaranteed Income.)

Next year Tubbs will launch the nonprofit End Poverty in California, which will explore, among other proposed policies, job guarantees and infant savings bonds.

“Politics is fundamentally not just about what’s right; it’s about having the power to enact what’s right,” he says. But when it comes to deciding whether or when he’ll reenter the arena, he’s somewhere between noncommittal and blessedly content.

“Who knows in the next 50 years whether I’ll run again,” Tubbs said on a local news program this month. “But I’m really enjoying this next chapter of helping politicians, being involved in policy, but also spending time with my two kids and my wife, going to the beach, wearing T-shirts. So it’s a good life.”

It’s a life Tubbs says he wants to spend making it possible for others to follow a path as fortunate — for all its twists — as his.

“It’s not about ‘Wow, how did Michael Tubbs become mayor?’” he says. “It’s about ‘How many people have we missed out on because they have to go through all these structural barriers to become mayor? How much talent and brilliance trapped in poverty, in violence, or any number of isms, are we missing out on?’”

Or, as he puts it in his memoir’s dedication, borrowing again from Tupac, “For Malakai and Nehemiah: You deserve a world where roses grow on rosebushes.”

More to Read

Sign up for our Book Club newsletter

Get the latest news, events and more from the Los Angeles Times Book Club, and help us get L.A. reading and talking.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.