‘I’m used to not winning’: South African novelist Damon Galgut on his Booker Prize victory

- Share via

On the Shelf

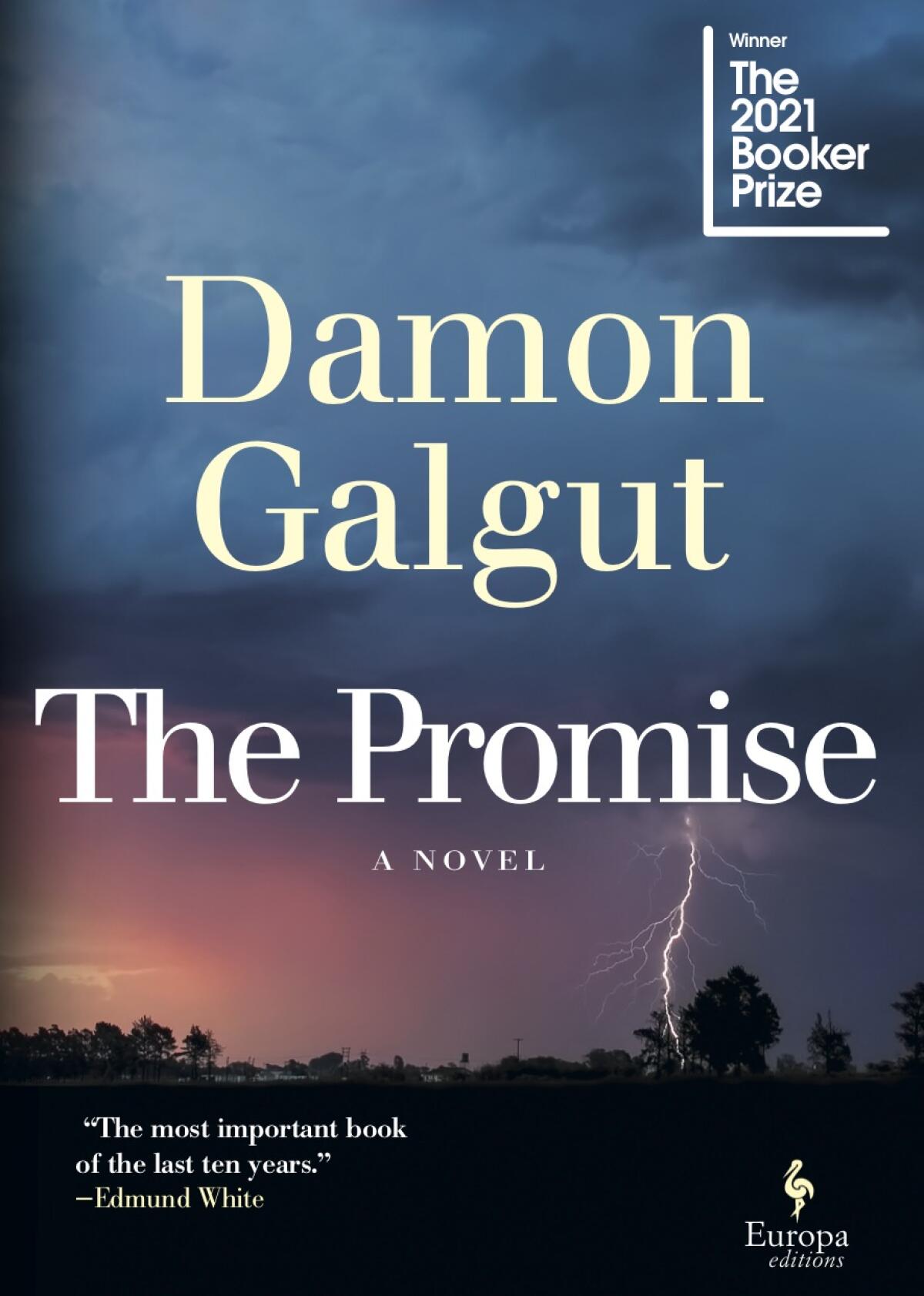

'The Promise'

By Damon Galgut

Europa: 256 pages, $25

If you buy books linked on our site, The Times may earn a commission from Bookshop.org, whose fees support independent bookstores.

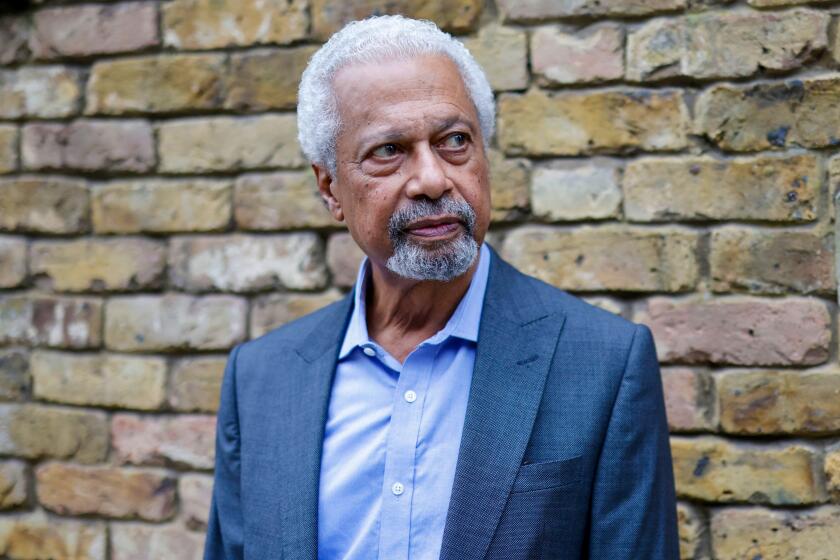

On Nov. 3, when the jury of the Booker Prize decided to give Britain’s most prestigious fiction award to South African writer Damon Galgut, 58, they surprised no one more than the author himself. “I’m used to not winning — that’s kind of what I’m programmed for,” he joked. Indeed, he had been shortlisted twice before, for “The Good Doctor” in 2003 and “In a Strange Room” in 2010. But this year, things turned out differently. “The Promise,” his formally inventive, kaleidoscopic novel of a splintering — and dying-off — white South African family, was hailed as a masterpiece “dense with historical and metaphysical significance.” Galgut recently spoke with The Times about the Booker roller coaster, as well as the failed hopes of both his fictional Swart family and South Africa, in a conversation edited for clarity and length.

Congratulations again on your Booker. What has the overall experience been like for you?

It’s been overwhelming, in both a good and a bad way. Writers struggle, mostly in vain, for any sort of attention or recognition, so of course it’s gratifying to receive both in such abundance. On the other hand, I’m not temperamentally suited to this onslaught. I’m a fairly quiet and private person, and not much given to talking about myself.

What has the reaction been like in South Africa? You’ve joined a very elite group of South African winners, including Nadine Gordimer and J.M. Coetzee.

The response here has been gratifyingly positive. Unfortunately, that’s somewhat undercut by the near-complete lack of attention from the local English press prior to the Booker shortlisting. In general, writers [and other artists] have to be validated by achievement overseas before they’re taken seriously here at home. I would also note that our Department of Arts and Culture, for a long time already a joke amongst the creative community, has failed to register even the smallest response to the news. I don’t care, personally speaking, but it does underscore how little they value the people whose interests they’re supposed to represent. I don’t think they’re doing it deliberately; they’re just comatose, which is worse.

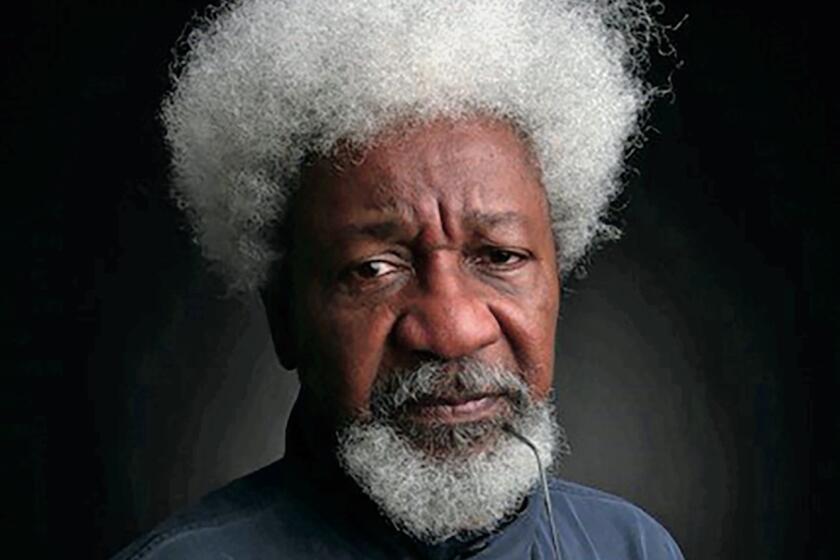

Much of the world may consider him obscure, but to generations of writers with African roots, Abdulrazak Gurnah is both an influence and a role model.

This year’s Nobel, Booker and Prix Goncourt — among other top awards — all went to African authors. As you said in your acceptance speech, it has been a great year for African writing. Do you think there’s a greater appreciation of this literature in the West?

I can’t really speak to how the West perceives African writing. I would hope this turns up the volume from our side and that it’s heard more clearly on the other. As for publishing and reading in Africa, that may be where the great part of the problem lies. It can’t be incumbent on the West to provide the only publishing platform for Africa; we have to do that for ourselves.

“The Promise” is in many ways your most ambitious work, particularly in the use of a roving, panoramic perspective. What prompted this fresh approach?

It’s always exciting to feel you’re working inside a tradition to subvert or expand it. I felt I managed that to a certain extent with the discovery of a narrative voice that breaks the usual rules. As I’ve spoken about to the point of nausea (my own, at least), I discovered this voice by accident, by transplanting the logic of film to prose. That’s opened my mind to the possibility of using other disciplines to shake up my own. Let’s see what happens.

The Swarts, you write, are “just an ordinary bunch of white South Africans. … Something rusted and rain-stained and dented in the soul.” And yet they are by no means homogenous.

Well, because white South Africans aren’t a homogenous entity. My own family, to take just one example, comprises Jewish, Scandinavian, English and Afrikaans elements, with all their attendant creeds. The colonies were all melting pots of this kind. Many of the postcolonial conflicts that afflict societies like ours stem from a nostalgic desire to separate “pure” roots from the imbroglio — a clearly futile exercise. In fact, I take the mix of cultures and communities as a hopeful signpost to the future. South Africa would be a lot better off if we all regarded ourselves as a mixture of races and stopped fighting for the rights of separate groups.

South African writer Damon Galgut has won the 2021 Booker Prize for his family saga “The Promise.”

One of the book’s most intriguing relationships is the one between Amor, the youngest Swart daughter, and Salome, the family’s longstanding Black maid. “They’re close, but not close. Joined but not joined,” you write. “One of the strange, simple fusions that hold this country together. Sometimes only barely.” What were the challenges of writing Salome?

Salome is absolutely tangible, a figure I know from everyday life. But in fact I chose not to give her character much weight or substance in the book, but rather to outline her through the perceptions of the white characters around her. Why? Because that’s exactly how such a person continues to be seen (or not seen) in South Africa now. In other words, she is somebody voiceless, with almost no “presence” in our society. To my mind, that’s a shame and a stain on the so-called “new” South Africa. It’s proven to be a somewhat contentious choice, with several [British] critics faulting me for not giving her an interior life of her own. But to my mind, that would have diminished rather than amplified her. I wanted her to be a bothersome blank spot on the map, a question without an answer. I was gratified in a couple of recent conversations with fellow African writers that my approach wasn’t seen as problematic in the slightest. As one of them said, “They don’t understand because they don’t come from where we do.” That’s exactly right.

Each section revolves around a Swart family funeral in a different decade under a different regime, ranging from the apartheid-era 1980s to the reign of Jacob Zuma. What do you make so far of the country’s direction under Cyril Ramaphosa, a successful businessman who many hoped would stabilize the country after the turbulent Zuma years?

It gives me no pleasure to say I think President Ramaphosa will be remembered as a well-meaning and mostly ineffectual leader. His heart seems to be in the right place, but he believes he can negotiate and charm his way into changing a culture riven with corruption and self-interest. You can’t fight gangsters with silk gloves and a cane. He needs to put on chain mail and knuckle-dusters and go down into the arena like Rambo.

The Nigerian writer, the first sub-Saharan winner of the Nobel Prize, discusses ‘Chronicles from the Land of the Happiest People on Earth.’

Tepper has written for the New York Times Book Review, Vanity Fair and Air Mail, among other places.

More to Read

Sign up for our Book Club newsletter

Get the latest news, events and more from the Los Angeles Times Book Club, and help us get L.A. reading and talking.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.