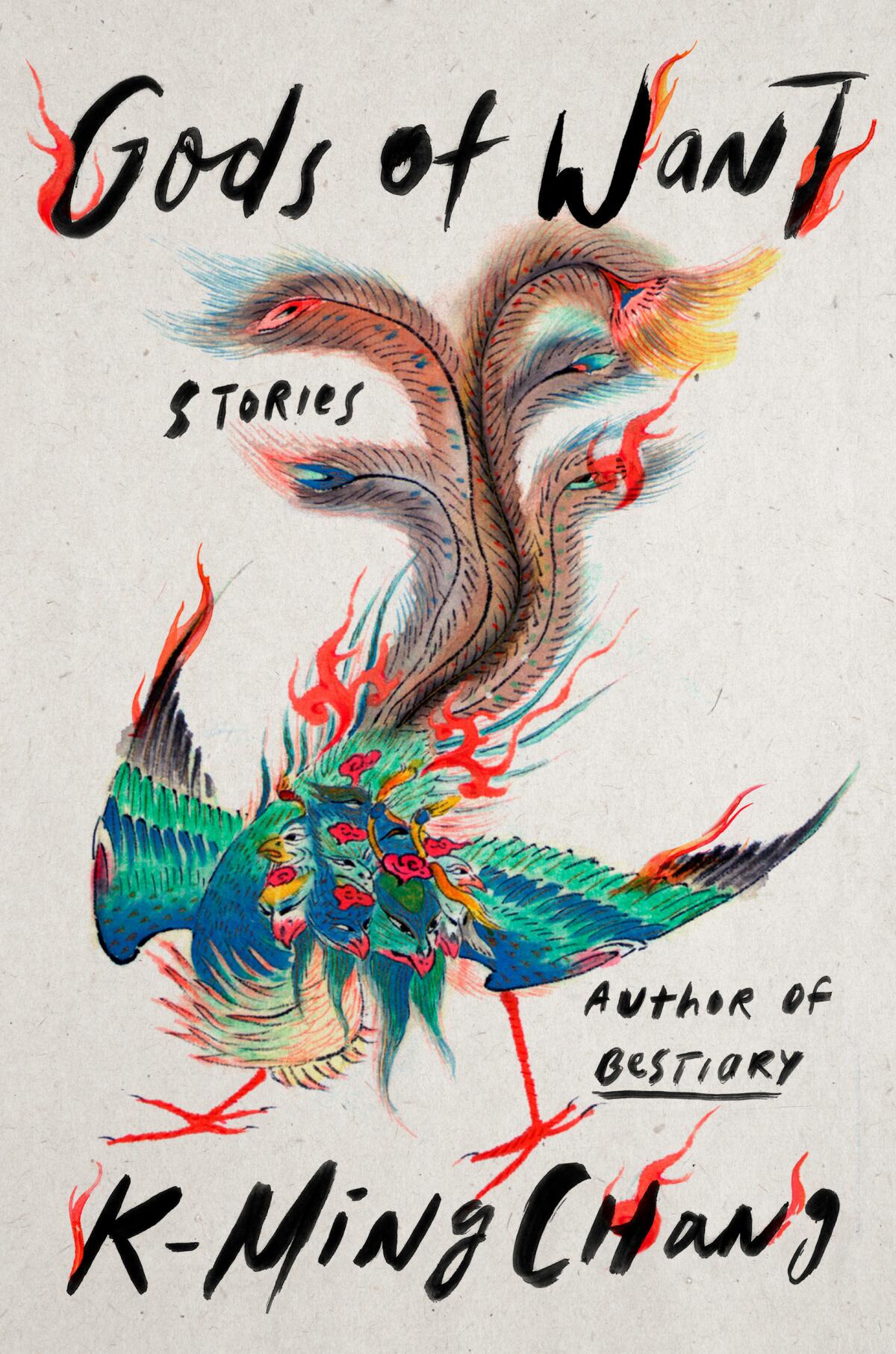

Review: A Taiwanese Californian’s mythical-realist tales of displacement and queer desire

- Share via

On the Shelf

Gods of Want

By K-Ming Chang

One World: 224 pages, $27

If you buy books linked on our site, The Times may earn a commission from Bookshop.org, whose fees support independent bookstores.

In “Nine-Headed Birds,” a story about halfway through K-Ming Chang’s new collection, “Gods of Want,” the narrator describes how her jiujiu (maternal uncle) took her to amusement parks and lent her coins to put through those penny-flattening machines. “I loved how skin-thin it was in the end, how the penny resembled none of the presidents,” she tells us. “I loved how easy its history was rewritten, forged into fiction.”

Chang has a special talent for forging history into myth and myth into present-day fiction. Her debut novel, “Bestiary,” “bursts open like delicious fruit on the edge of rot,” as Bethanne Patrick wrote in The Times’ review, full of lyrical imagery and a setting in which “the reality is harsh and the magic is real.”

Like “Bestiary,” the 16 mytho-realistic stories in “Gods of Want” are set among Taiwanese immigrants and first-generation Americans, mostly in California. They also use similarly poetic language to explore some of the same themes — family, stories passed through generations, queer desire, the aliveness of the mundane world around us. That is not to say Chang is repeating herself: Only that like many authors, she orbits around specific artistic obsessions and sensibilities. The stories are divided into three sections, “Mothers,” “Myths” and “Moths,” although references to all three spill over into most of the pieces.

K-Ming Chang’s debut novel, about three generations of Taiwanese immigrants, documents abuse, queer coming-of-age and a daughter’s troublesome tiger tail.

Some of the stories are less conventional than others. The first, “Auntland,” is written as a breathless list of such women and their actions: an aunt who asked to get her tongue pulled at the dentist, another who tweezed out bits of broken tooth from the narrator’s mouth, a third who kissed another woman when she thought no one was watching and many more. Whether the aunts in the narrator’s litany recur or each is entirely distinct is unclear — and it doesn’t really make a difference; the point is that there is love woven into this enumeration of women and the wisdom, foibles, superstitions, pain and joy they pass on to the narrator.

The second story, “The Chorus of Dead Cousins,” has a more defined arc. The narrator here is a newlywed woman whose wife threatens to leave her just a week after their wedding, a direct result of dead cousins wreaking havoc. The narrator’s wife, who works as a storm-chaser, doesn’t herself like being chased by the storm of ghosts. The narrator, however, recognizes their often-good intentions.

“My wife said they were fluent only in the vocabulary of senseless destruction,” she says, “but weeks before we left, I saw the cousins in the backyard with shovels. They were standing in a row like soldiers, and when I asked what they were doing, they said, ‘We’re making you a moat.‘’” Actually, it’s a firebreak. The cousins know it’s wildfire season and they mean to protect their living kin.

The book draws its title from the story “Eating Pussy,” whose narrator is named Pity. (“People always replied, ‘Pretty? That’s nice.’ I’d say ‘No, not Pretty,’ not even when I dyed my hair ash-blond with the box dye I shoplifted from Daiso.”) Another girl, Pussy, is mocked at school for her fresh-off-the-boat name, but Pity is enchanted with her and suggests they pair up for the school talent show.

Pity’s talent, which she seems to make up on the spot, is being able to eat anything, which she proves by picking up a handful of tanbark bits and swallowing them, splinters and all. Later, Pussy challenges Pity to eat her whole and regurgitate her backstage. Pity, eager to keep impressing her new friend, tells her to kneel, and watches as, behind her, “in the trash creek, a raccoon [runs] across the clogged surface of the water, a glass bottle in its jaws, god of want.”

‘Fiona and Jane,’ Jean Chen Ho’s collection of stories, pays homage to friendships complicated by displacement, sexuality and the passage of time.

The story amounts to an extended pun on the title, making a metaphor out of the stirrings of preadolescent desire. Want is one of the collection’s major themes, especially in the sense of sexual and sensual desire — always for and between girls or women, never catering to the male gaze. “Gods of Want” is in some ways a fantasy of queer freedom. Its main characters, all Taiwanese or Chinese by birth or descent, are allowed to be who they are, to love and make love to whomever they choose. This isn’t to say relationships or dalliances are always easy or successful. In “Dykes,” the narrator wonders what her co-worker Ail’s nipples might look like. When Ail tells her she can look if she wants, the narrator is suspicious, knowing “all wants were weapons that could be turned on you anytime.”

In addition to the characters’ desires, whether enacted or merely fantasized, “Gods of Want” is unified by recurrences of word and image. Teeth — molars specifically — are featured in several stories, as are moths. At least two broken noses appear, as do mouths that are literally shot into silence; “hip,” “crown” and “razor” are repeatedly used as verbs, and heads are compared to melons more than once.

At first I thought these were linguistic tics, but as I read the book a second time, they became bread crumbs for a careful reader. They offer up the possibility that several of the stories are narrated by the same person at different times in their life, or that characters in certain stories might know those in others. Perhaps they all inhabit the same fictional community, or several communities that mirror one another. But even if this is not the case, the recurrences create the sense across the stories of a shared history — of colonization of land and language, of immigration, of desire — as well as a shared wealth and depth of myths through which to view the world’s cruelties and glories alike.

Masad is a books and culture critic and author of “All My Mother’s Lovers.”

More to Read

Sign up for our Book Club newsletter

Get the latest news, events and more from the Los Angeles Times Book Club, and help us get L.A. reading and talking.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.