Review: How Black country music became undeniable

The Country Music Assn. Awards in 2016: Beyoncé, center, performs with the Chicks, then known as the Dixie Chicks.

- Share via

On the Shelf

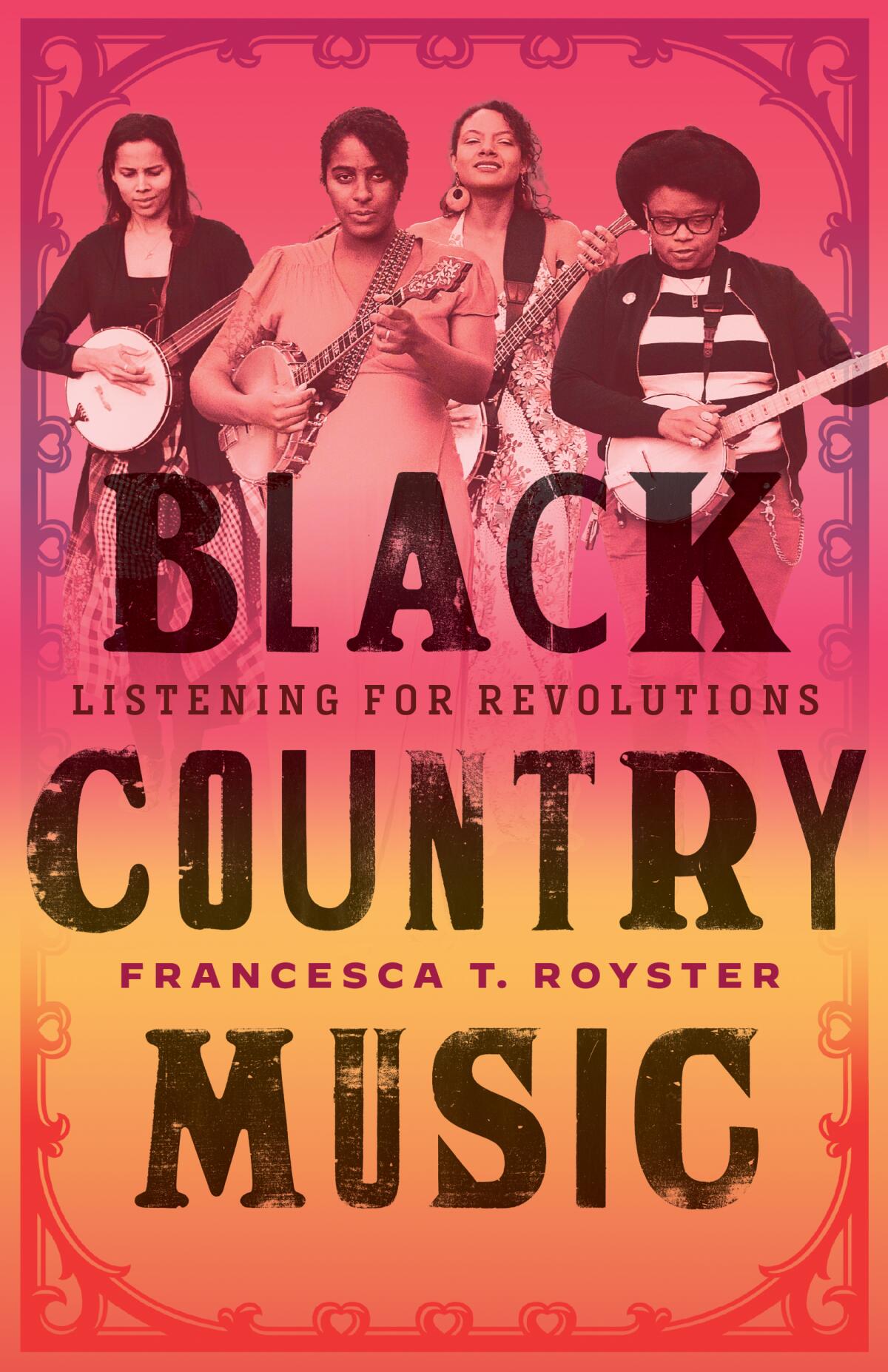

Black Country Music: Listening for Revolutions

By Francesca T. Royster

University of Texas Press: 248 pages, $25

If you buy books linked on our site, The Times may earn a commission from Bookshop.org, whose fees support independent bookstores.

In the introduction to her new book, “Black Country Music: Listening for Revolutions,” Francesca Royster recalls a country music festival she attended in her hometown of Chicago in July 2014. A Black woman at an overwhelmingly white event, Royster approached the few other Black people she’d spotted. “Why are you here?” she asked them. Was it for the music? Every single one demurred: “Sorry, I don’t know a thing about country music.” “Sorry, I can’t help you.” “Sorry, I’m just here for the BBQ.”

These dismissive responses, Royster believes, came less from a place of sincerity than an impulse of self-protection. Maybe each of these folks really had dropped 40 hard-earned dollars for the simple pleasure of sitting outside on a warm day with a paper plate of barbecue; maybe they didn’t even notice the white men on stage with their cowboy hats and fiddles. “Or maybe I was asking a fundamentally uncomfortable question,” Royster writes, “bringing to light an awkwardness that most of us, as we navigate white spaces, might try to ignore or suppress in order to enjoy ourselves.”

Greg Tate was part of a powerful tradition of Black criticism. Its inheritor is Hanif Abdurraqib.

Royster, a professor of English at DePaul University, doesn’t dwell in her book on why country music has been such a longstanding taboo for Black Americans. Instead she reflects on the many ways Black artists have challenged expectations and stereotypes. “Black people are always inventing new ways to survive the unfreedoms of white supremacy,” she writes, “and this includes country music.”

The last few years have been pivotal for Black country artists and their fans. Black country musicians today are seen, heard and valued as never before in the genre’s long and troublesome history — topping charts, earning prestigious awards and collaborating with country royalty. Their emergence (or rather, recognition) has been the subject of radio shows such as Rissi Palmer’s “Color Me Country” and Willie Jones’ “Cross Roads Radio,” as well as the 2022 documentary “For Love & Country.” A collective and touring revue, Black Opry, is currently selling out venues from Nashville to New York, with an upcoming appearance at West Hollywood’s Troubadour. This year’s popular Stagecoach and Palomino festivals, in Indio and Pasadena, respectively, featured many Black performers, including Valerie June, Rhiannon Giddens, Breland, Reyna Roberts, Yola and Amythyst Kiah.

Royster’s book, however, isn’t so much a history of the African American experience in country music — editor Diane Pecknold’s 2013 anthology, “Hidden in the Mix,” better explores that story. “Black Country Music” is more of a hybrid of memoir, critical analysis and journalism focused on a few select contemporary artists and their singular contributions to the genre.

Royster writes with an academic’s scrutiny, frequently referencing and quoting from Audre Lorde, Daphne Brooks and bell hooks, among many other scholars. But she also brings her personal story into the analysis, approaching country music from the perspective of a Black, queer woman for whom copping to a love of the genre is akin to coming out of the closet.

She argues that “Black country” is set apart from mainstream country and more akin to Afrofuturism, writing that the “unpredictable innovation of Black art forms,” including country, “can be tactics to subvert appropriation and the control and constraints of white supremacy, especially as they take advantage of new platforms and forms of distribution.” This combination of theoretical rigor and a highly specific point of view may not be for everyone, but Royster never pretends to be definitive; hers is more a personal meditation on country music than a survey of its past and present. What motivates her work is her enjoyment of the genre and her desire to find her place in it.

One of the largest country music festivals in the world is back after its pandemic-induced hiatus.

Each chapter focuses on one artist, and her choices can be surprising. Beginning with Tina Turner — whose 1974 debut solo album was a collection of country covers — and moving on to Darius Rucker (an obvious choice) followed by Beyoncé (a less obvious choice), Royster’s interpretation of “country music” is subjective, though not without intention. Still, in such a slim book, does an entire chapter dedicated to Beyoncé merit inclusion?

Royster makes the case that it does, focusing on how even an artist at her level of fame can be hemmed in by racially motivated notions of genre boundaries. Beyoncé’s performance of her single “Daddy Lessons” at the 2016 Country Music Assn. Awards alongside the Chicks (née the Dixie Chicks), was met with criticism from conservative country fans and commentators who were angered by the inclusion of a pop singer at the CMAs, by Beyoncé’s support of Black Lives Matter or simply by the inference that “Daddy Lessons” was a country song.

In writing about backlash to the outlaw country-tinged “Daddy Lessons” — which mimics the “Texas justice” tropes of westerns and desperado ballads — Royster points out that rebellion and anti-authoritarianism are celebrated when performed by such artists as Waylon Jennings, Willie Nelson and Merle Haggard, but these privileges don’t typically extend to others who play on this tradition. “Country music has made room for its white male country outlaws,” she writes, “even if it doesn’t always make room for outspoken Black women.”

Royster’s writing is sometimes conjectural, other times pedantic, but in many passages her prose soars, particularly in her chapter on Valerie June.

“Her voice slips through our ribs, like a ghost, attracted by our hunger, by the space made for her in our shrunken, unfed bellies,” she writes of June. For Royster, June’s voice “conjures up ghosts” — the ghosts not only of June’s musical predecessors, including Jessie Mae Hemphill, Elizabeth Cotten and Geeshie Wiley, but also the ghosts of ancestors near and distant. She wonders how June’s voice can sound like “both your mama’s voice calling you in when the streetlights come on and yourself singing to yourself while you fold laundry?”

Though neither exhaustive nor conclusive, “Black Country Music” is nonetheless an original, timely and much-needed entry in the long-overdue national conversation on representation and accountability in the country music industry. As Black country creators and fans alike continue to receive greater recognition, Royster imagines a future in which her question — “Why are you here?” — yields more satisfying, or more honest, answers.

Why are we here? Because we belong here.

Justin Tinsley’s ‘It Was All a Dream: Biggie and the World That Made Him’ contextualizes the short life and immortal art of a one-of-a-kind rapper.

Holley is a journalist and author of the forthcoming book “An Amerikan Family: The Shakurs and the Nation They Created.”

More to Read

Sign up for our Book Club newsletter

Get the latest news, events and more from the Los Angeles Times Book Club, and help us get L.A. reading and talking.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.