A Mexican journalist was murdered. It wasn’t the end of the story

- Share via

On the Shelf

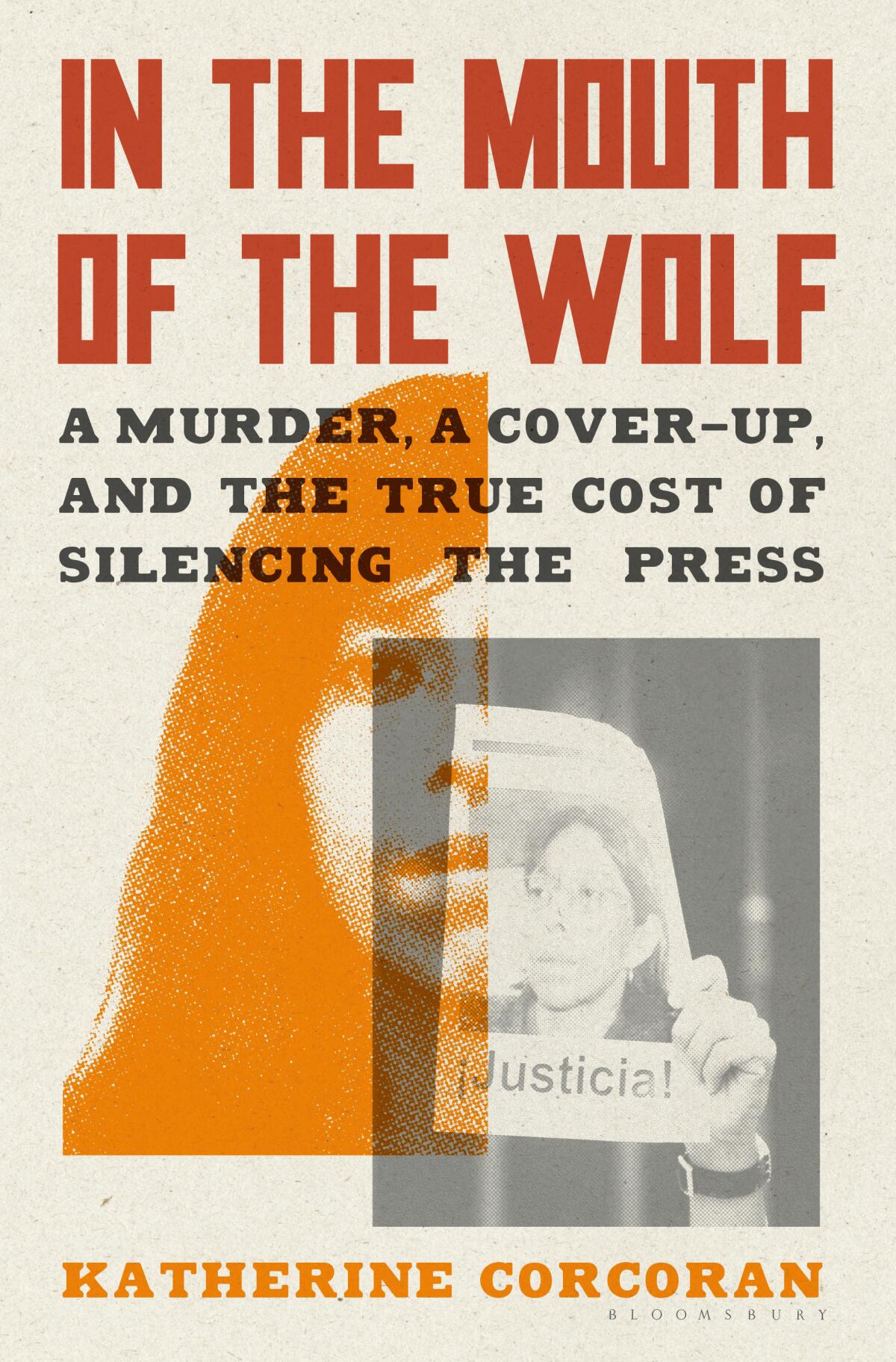

In the Mouth of the Wolf: A Murder, a Coverup, and the True Cost of Silencing the Press

By Katherine Corcoran

Bloomsbury: 336 pages, $28

If you buy books linked on our site, The Times may earn a commission from Bookshop.org, whose fees support independent bookstores.

The assassination of Regina Martinez in 2012 was horrific: a respected Mexican investigative journalist brutally beaten in her home before being killed. But it was the context surrounding her death that was especially distressing: 10 journalists had been killed in Mexico in 2010 alone; Martinez was the fifth killed in the state of Veracruz since Javier Duarte became governor in 2011. (Duarte is now in prison for embezzling billions of dollars.) The government’s investigation into the journalist’s death was clearly a sham, built on propaganda and false arrests.

Most Americans are unaware of tragedies like this one. Or if they heard about this one back then, they presumed it was just another case of drug cartel violence. Katherine Corcoran’s new book, “In the Mouth of the Wolf,” aims to uncover the truth behind Martinez’s murder while also underscoring the larger implications for civil society — and not just in Mexico.

Corcoran was the Associated Press regional bureau chief based in Mexico City in 2012. While she’d only briefly encountered Martinez, she was familiar with her work and knew that the killing of a journalist of her national reputation was a step beyond even for Mexico — even for Veracruz under Duarte.

“My first motivation for investigating this was that there were so many unanswered questions around these journalist killings, and I thought I could clarify more definitively what was behind them,” Corcoran said in a recent video interview from Indiana, where she’d been speaking at the University of Notre Dame, her alma mater. (She still spends most of her time in Mexico City.) “It was only getting worse, and I thought the only thing I can do as a foreign journalist is bring the story to a wider audience. Maybe that would cause more concern in Mexico.”

In her early years reporting on the case, Corcoran saw this as a definitively Mexican story, not something related to journalism in the U.S. “But then the whole context here changed and it became cautionary tale,” she said, pointing to a hostile environment for the American press thanks to the arrival of a demagogic president who attacked the truth as “fake news” and journalists as the “enemy of the people.”

This article was originally on a blog post platform and may be missing photos, graphics or links.

“Something that would have ruined someone’s political career 10 or 20 years ago — like Herschel Walker paying for abortions — is just shrugged off, which has to do with the idea that facts aren’t important,” Corcoran added. “In political campaigns we’re seeing ‘unfriendly’ media being excluded from events. The idea that politicians only want a mouthpiece is common in a way we’ve never seen before.”

This, she said, is exactly how the system functions in Mexico, and we should read her book not merely as the investigation of a corrupt land beyond our borders but as a harbinger of our future at home: “We have traditionally felt none of this stuff could happen in our system, but I wanted to show the erosion has already started.”

Corcoran doggedly pursued evidence to try to pin down the person or people behind the killing. She interviews journalists, family members and others about what stories Martinez had been working on and who might have felt threatened. She also dug into everyone linked to the case in any way.

Many times Corcoran almost walked away, both because so many people were uncooperative, leaving her stuck in numerous dead ends, and because she feared for the safety of those who did cooperate, especially Martinez’s nephew and the journalists who had worked with her. (Only two people took Corcoran up on her offer to change their names. “I wanted to show how brave these people are in the face of these risks to get this story out,” she said.)

But the book also strives to bring Martinez, her friends, her mentees and her enemies to life, creating a portrait of a culture where official autocracy is barely in the rear-view mirror and intrepid journalists struggle — frequently at great personal risk — to prompt change or at least some accountability.

The recent killings of two journalists within a week in the northern border city of Tijuana have fanned outrage.

While Corcoran narrows her gaze to a single suspect by the book’s end, that ultimately was not her main concern.

“I discovered enough for an angle of investigation by authorities,” she said of her prime suspect. He still wields power in Veracruz and the government doesn’t seem inclined to pursue the case. “But you never know. Politics is always changing, so it’s worth putting this out there. Still, the rest of the story is as or maybe more important than the whodunit. I wanted to explain the why.”

Narcotics have been responsible for some journalists’ deaths, but Martinez’s case was more devastating because her killer walked the halls of power.

“There’s a criminal governance in Mexico that is sometimes aligned with the narcos but sometimes is just the people in charge creating their own criminal enterprises,” Corcoran said. “I wanted to explain to the world what is behind this. Outside of war zones, when journalists are attacked it’s more often because they are uncovering criminal activity by the government. These governments prey on their own people and that’s why they need the silence.”

Even though the book is done, Corcoran remains committed to holding those in power accountable in Mexico and beyond. “I’m not going to drop the subject because it’s very important,” she said, “and I see parallels between Mexico and what’s happening in the United States.”

Ioan Grillo’s “Blood Gun Money” traces the escalating drug wars in Latin America to the “iron river” of automatic weapons from the tragically lax U.S.

Corcoran runs a program with a Mexican journalist training editors in investigative reporting. It is crucial, she says, as Mexico appears to be backsliding. The country had seven decades of one-party rule before creating multi-party elections, but she says free elections without institutional reform leave the country open to autocracy’s return.

Journalists have been complicit in this. Corcoran’s book documents how pervasive corruption has been in the press. Some reporters were easily bought off while others held back out of fear for their lives. Violence persisted because it worked: “Part of the reason so many journalists were killed was the press reaction was to silence itself and shut down, which was what they wanted.”

This at least, Corcoran believes, has begun to change: “The quality of journalism is improving and there is also a dramatic increase in the solidarity among the journalists.”

She hopes her book can also shine some light closer to home. “We have to help the public understand what we do,” Corcoran said. “When you make decisions about voting or hear about contaminated water supplies, it’s journalists who uncover that and help people live their lives. Independently reported information is necessary to the freedom of society.” This is one unchangeable fact, Corcoran believes, that knows no borders.

Zapata, who died this month, wrote 1979’s “The Vampire of Colonia Roma,” a turning point for LGBTQ culture at the height of Mexico’s authoritarian regime.

More to Read

Sign up for our Book Club newsletter

Get the latest news, events and more from the Los Angeles Times Book Club, and help us get L.A. reading and talking.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.