Sci-fi master Jeff VanderMeer’s reissued debut shows how his grotesqueries have grown

- Share via

Review

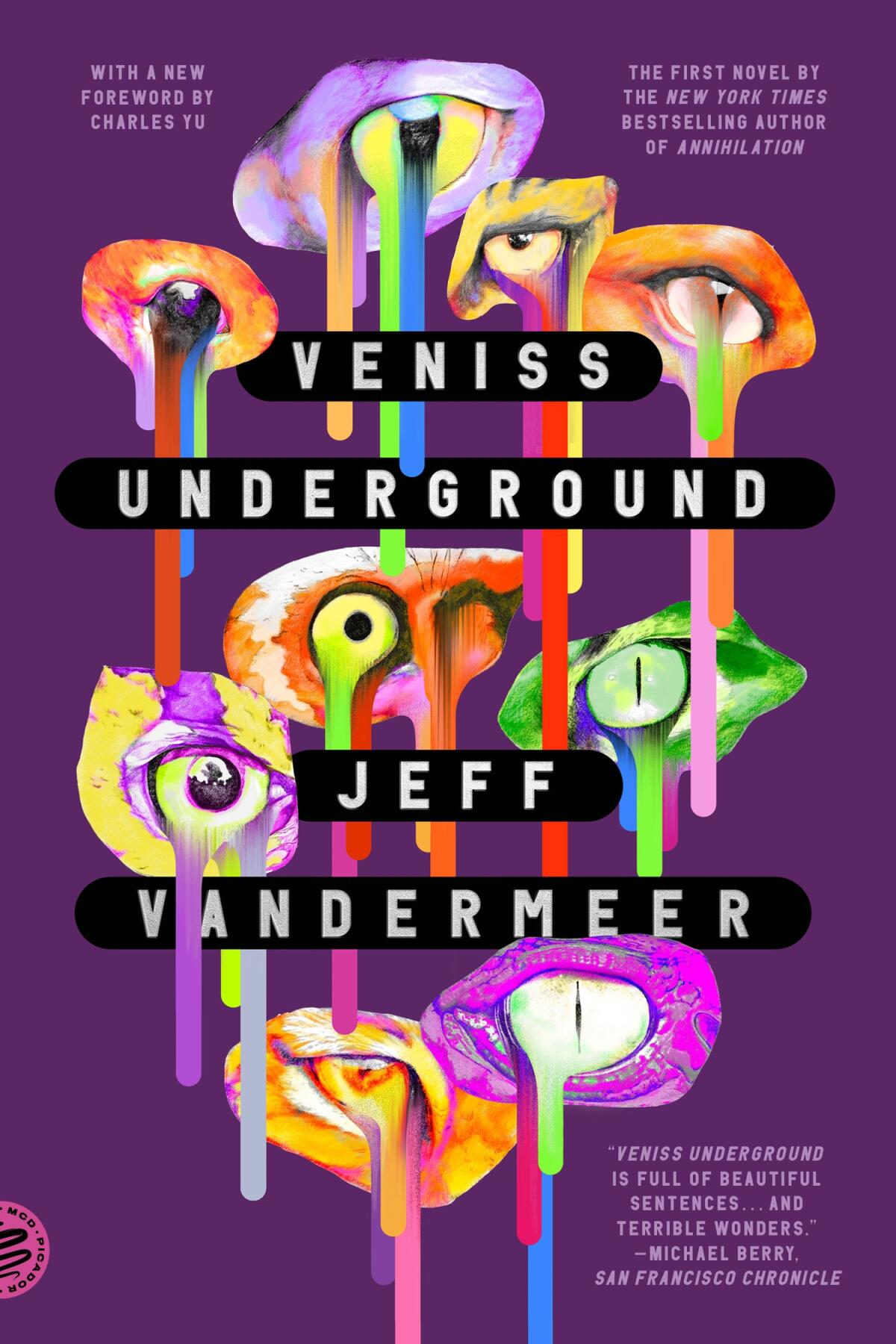

Veniss Underground

By Jeff VanderMeer

Picador: 336 pages, $19

If you buy books linked on our site, The Times may earn a commission from Bookshop.org, whose fees support independent bookstores.

“They could never believe in a giant fish that holds a whole world. They’d laugh. They’d scoff. Even if they saw it, they wouldn’t believe it. That is why the human race is dying — too limited an imagination.”

The above quote from Jeff VanderMeer’s first novel, 2003’s “Veniss Underground,” is a kind of statement of purpose for his career. As one of the leading writers of the New Weird, VanderMeer has taken it as his aesthetic and ethical task to push the bounds of the imagination to bizarre, absurd and disgusting extremes.

A new edition of the book, including related stories, fragments and commentary by VanderMeer, shows how consistent his methods and goals have remained over the last 20 years. It also shows, however, that even as he’s grown into a bigger fish, he’s become — admirably and definitively — weirder. In retrospect, “Veniss” is the relatively conventional, larval VanderMeer, before his metamorphosis into a truly bizarre, cancerous butterfly creature.

This isn’t to say his debut is drab or boring. Like much of VanderMeer’s work, it’s a wonderfully imaginative agglomeration of cyberpunk, Lovecraftian grotesquerie and magical realism. Set in a confused dystopian future, the novel follows three main characters — twins Nicholas and Nicola and Nicola’s lover Shadrach — as they attempt to confront the mysterious genetic engineer Quin and his manipulated monstrosities.

Among the highlights of the ensuing adventure is a hyper-intelligent meerkat assassin named John the Baptist, whose head is chopped off and glued to a plate; a creature named the Gollux that speaks out of its anus;, and that improbable world-fish, vast and open-mouthed, in which Quin makes his improbable lair.

A series of associated early stories — inspired in part, VanderMeer has said, by Ursula K. Le Guin — are included in this edition; they explore other narratives in the same world, treating the landscape as mythic history. A woman tries to find her husband, who has disappeared into a peripatetic and transcendent city; a brother and his Flesh Dog go on a quest to trade for a healthy heart for his sister; an old man defies the AI overlords to swim in the ocean.

Even at this early stage, VanderMeer’s imagination was a fertile birthing place for ugly, fleshy, oozing oddities, and he had a gift for filling in just enough of the world to make you feel like there was something even worse just around a corner you couldn’t see.

In later VanderMeer, though, the author is more willing to acknowledge that the thing around the corner is maybe a thing you want to see. In this early effort, the weirdness is still framed as a conventional antagonist. Shadrach, the upstanding hero of “Veniss,” goes into the underground to fight the disgusting things in the dark and then he crawls back into the light, heroic and basically unchanged, except perhaps purified. Clean and uncorrupted, he’s not that different from a hero out of Robert A. Heinlein. The twisted nightmares of bioengineering, with hideous orifices and unnatural urges, are bad; normal is good.

In ‘The Weird,’ Ann and Jeff VanderMeer air the eerie

VanderMeer’s later writing rarely puts you quite so straightforwardly on the side of the able-bodied and unmonstrous. His famous Southern Reach trilogy is about an alien infestation that transforms coastal wilderness into an even wilder wilderness. The protagonist, a biologist whose primary emotional relationship is with the ecosystem in a puddle, eventually morphs into a titanic Cthulhu-like sea creature. In doing so she takes on her true form, even as the alien landscape, scrubbed of its human infestation, is in some sense a truer, more ecologically sound version of the earth. You aren’t really rooting for the hero to conquer the weird. You’re rooting for the weird.

Similarly, in VanderMeer’s 2017 novel “Borne,” the titular character is a green lump, both a terrifying nightmare weapon and a cutie. The protagonist, Rachel, cultivates the thing as a kind of plant, then as a pet, then as a child. The meerkats who want to replace us in “Veniss Underground,” in contrast, are waging brutal war on humankind. The most powerful story in the new edition is about a war in which the meerkats kill humans and then place their consciousness into warrior flesh dogs they send against their former loved ones.

Borne too is frightening and amorphous; a terrifying evolutionary next step. But he’s also funny and intriguing. Borne “made me rethink even simple words like disgusting or beautiful,” Rachel realizes with wonder. Borne shows her new ways of thinking and being, and that’s why she loves him.

Bora Chung’s story collection, ‘Cursed Bunny,’ melds horror tropes with literary aspirations. The best of her tales are as eerie and deep as Kafka’s.

Weirdness has its own conventions; horror makes much of ichor and tentacles, of slithering and maws in the wrong places. Even in his early work, VanderMeer was able to rearrange those conventions in unusual ways. Over time, though, he began to explore the nature of monstrosity itself — how it might offer the opportunity to expand the perception of what is human and what is normal (or should be).

VanderMeer fans who missed “Veniss Underground” won’t be disappointed; it’s an enjoyable, thoughtful novel with a new weird idea on every page. But they’ll also be impressed with how the author has, over the years, cultivated his own aberrant growth, flowering into marvelous, decadent forms out of this misshapen seed.

Berlatsky is a freelance writer in Chicago.

More to Read

Sign up for our Book Club newsletter

Get the latest news, events and more from the Los Angeles Times Book Club, and help us get L.A. reading and talking.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.