Katya Apekina’s ‘Mother Doll’ isn’t your ordinary ghost story

- Share via

On the Shelf

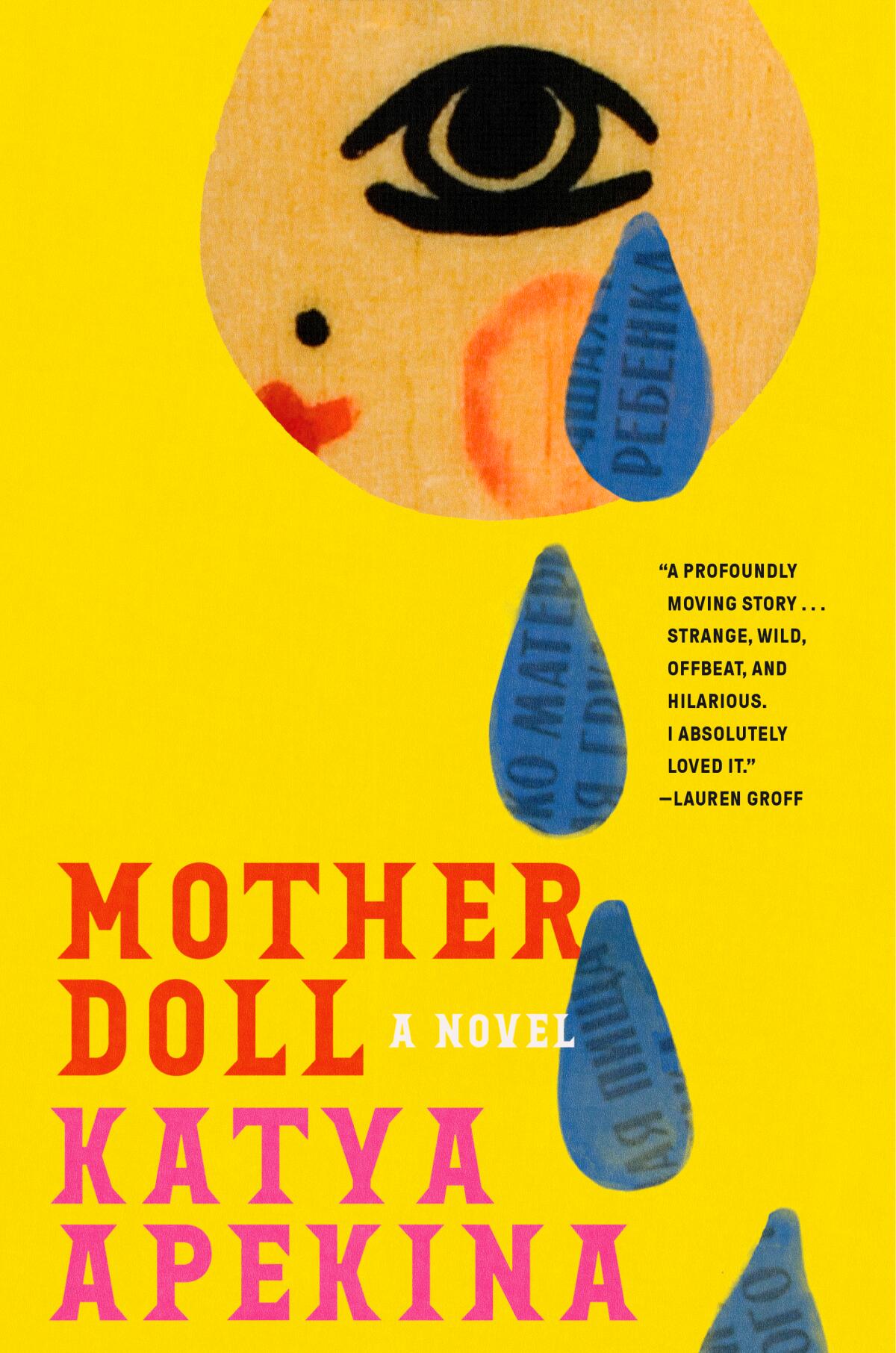

Mother Doll

By Katya Apekina

Overlook: 320 pages, $28

If you buy books linked on our site, The Times may earn a commission from Bookshop.org, whose fees support independent bookstores.

Katya Apekina has always been a little bit psychic.

When she was young, she knew her bond with her mother went beyond the usual connection that mothers and daughters share.

“We were so enmeshed,” Apekina told me at Tierra Mia, a coffee shop in walking distance from her Highland Park home where she’s lived for more than 10 years. “I would know right before she called.”

It wasn’t just her mother. She was also unusually in tune with her husband. “I could guess the number he was thinking of between one and 100. It was a different number every time. He wasn’t guessing 13 or 69 over and over again.”

Apekina’s interest in other ways of knowing informs her new novel, “Mother Doll,” a wild multigenerational story set both in modern-day Los Angeles and in Petrograd (now St. Petersburg) during the Russian Revolution.

In Emily Raboteau’s book of essays, ‘Lessons for Survival: Mothering Against “the Apocalypse,”’ her care for her neighborhood and her maternal care for her children are connected as she faces an uncertain climate future.

The novel opens with Zhenia, a young woman in her 20s, being blindsided by an unplanned pregnancy. The timing couldn’t be worse: Her beloved grandmother on the East Coast is dying and her husband’s acting career is finally taking off. Zhenia tries to turn to her grandmother for counsel, but her mother refuses to put her on the phone, insisting that she’s no longer lucid. So when Zhenia gets a call from a medium named Paul who claims to be in contact with her great-grandmother in the spirit world, she’s desperate enough to believe him.

Although Apekina shares some characteristics with Zhenia — she emigrated from Russia, grew up in Boston and moved to L.A. — her protagonist lacks her uncanny intuition. For Apekina, it’s not a matter of whether she believes in ghosts.

“If you’ve seen a ghost,” Apekina explained, “you don’t have to believe or not believe. You experienced it. It’s no longer in the realm of belief; it’s like an experience you had.”

Eager to learn more about the nature of her own experiences, Apekina signed up for psychic meditation classes at Zen Meditation in North Hollywood and described her sessions as a form of guided meditation.

“It was fascinating to just be in a kind of open state,” she said. “In a lot of ways, it felt like writing, that kind of channeling feeling. Not all the time — I wish it was like that all the time — but when it’s going well it feels like you’re channeling, just typing whatever’s coming through.”

When the pandemic hit, Apekina took a mediumship class over Zoom during which the teacher channeled people as a medium. That seemed like an unusual way to access the spirit world, but Apekina kept an open mind.

“It was great until my grandfather died,” she said. “We were very close and I really wanted to talk to him, but I just felt so gross about it because it felt fake. It felt like my desire for it to be real was so strong that I was trying to convince myself.”

While wrestling with the limits of her own credulity, her grandfather came to her in a dream that night.

“It was just his voice in my ear,” Apekina explained. “He said my name and I immediately woke up, terrified. ‘I’m not ready for this,’ I thought. ‘I don’t want this at all.’”

Apekina had already started working on “Mother Doll” and her personal interest in psychics and mediums became research for the work in progress. Her discomfort with being contacted by her grandfather is played out in Zhenia’s reluctance to accept that she’s in touch with her great-grandmother Irina, who played a murky role in the Russian Revolution and whose past Zhenia’s mother kept shrouded in secrecy.

Apekina already knew she wanted to write about the revolution and the novel started to coalesce several years ago after a trip to Mexico City where she visited Trotsky’s house.

“I didn’t know what the story was going to be or who the characters were,” she said. “I was kind of feeling it out and doing a lot of reading and research.”

Without even the slightest sentimentality about it, Laird Hunt’s new book, ‘Float Up, Sing Down,’ provides an elegy for a lost generation.

She always knew that her approach — as in her first novel, “The Deeper the Water the Uglier the Fish” — would be unconventional. “When I talk about ‘Mother Doll,’ I say, ‘it’s about ancestral trauma, but funny!’”

“‘Mother Doll’ is riotously funny,” said Ruth Madievsky, an L.A. novelist and poet who emigrated from Moldova when she was 2 years old. “Apekina’s horny great-grandmother, ghosts and heads rolling down the street ‘like cabbages’ will stick with me for a long time.”

The novel’s unusual plot mechanics are sustained by her wry observations and wicked sense of humor. “Katya has a way of writing and managing the most devastating experiences of her characters with a lightness that never detracts from the profound weight of her bigger project,” said novelist Ottessa Moshfegh, who often blends the traumatic with the absurd in her own work.

Not all of the inspiration for “Mother Doll” came from beyond. Apekina drew from the unpublished memoir her grandmother left her after she died. She said, “It was like having a conversation with her through her writing even though she was dead. I was thinking about talking to the dead.”

While none of the characters in “Mother Doll” are based on Apekina’s relatives, their stories and experiences helped her bring them to life.

In many ways, her novel embraces the dream logic of Russian magical realism, such as Mikhail Bulgakov’s “The Master and Margarita.” Although Apekina read plenty of Russian literature when she was a child, she was also drawn to page-turners for children and young adults by Christopher Pike and R.L. Stine.

“I really loved these pulpy novels, but I’d have to read them in secret while I was also reading ‘War and Peace’ or whatever in sixth grade.”

Patti Davis has spent a lifetime chronicling her life with parents Ronald and Nancy Reagan. In a new book, ‘Dear Mom and Dad,’ she reckons with them as people, not parents.

Apekina brilliantly balances the bizarre with the mundane. “On one level,” Moshfegh said, “her descriptions are so frank, so astute and so smart, I’m put at ease, thinking, ‘Here I am in a world that has been observed and transmitted to me so keenly, it feels absolutely real.’ But then she makes these audacious, dangerous moves in the story that are just boggling and fantastic, and I think, ‘This is new, this is magical, and yet this feels absolutely real too.’”

The novel is at its most real when it comes to the particulars of Zhenia’s pregnancy. Apekina’s story swings from the matter-of-fact physicality of one body inside of another to the mind-bending possibilities of disassociated consciousness. Zhenia’s ancestors speak to her in all manner of ways — from genetics to direct communication. She becomes a Matryoshka doll in every way imaginable.

“Mother Doll” isn’t a ghost story but a meticulously layered tale of fabulist historical fiction where the details of the Russian Revolution are related with the same depth of detail as a trip to L.A.’s Magic Castle. That said, Apekina hopes her novel isn’t branded as “supernatural.”

“I think it would be a little misleading. I don’t think it feels like a ghost story. It just happens to have a ghost in it.”

Apekina will discuss her new novel with Moshfegh at 7 p.m. Wednesday at Skylight Books.

Ruland is the author of “Corporate Rock Sucks: The Rise and Fall of SST Records” and “Make It Stop.”

More to Read

Sign up for our Book Club newsletter

Get the latest news, events and more from the Los Angeles Times Book Club, and help us get L.A. reading and talking.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.