At Sundance, two female filmmakers share the struggle of jumping from documentary to narrative

- Share via

PARK CITY, Utah — When this year’s Oscar nominations were announced and four female filmmakers were recognized in the documentary feature category — but none in directing — Liz Garbus tweeted this:

“Celebrate the achievement of women in docs but remember that the financial bar for entry in docs is so much lower. When the opportunities are there, women shine. Makes the lack of representation in the larger budget categories more shameful.”

Garbus would know. She’s been making documentaries for over two decades — a career that launched when her first nonfiction movie, “The Farm: Angola, USA,” was awarded the Grand Jury Prize at the Sundance Film Festival. (It went on to receive an Oscar nomination for documentary feature, as did her 2015 film “What Happened, Miss Simone?”)

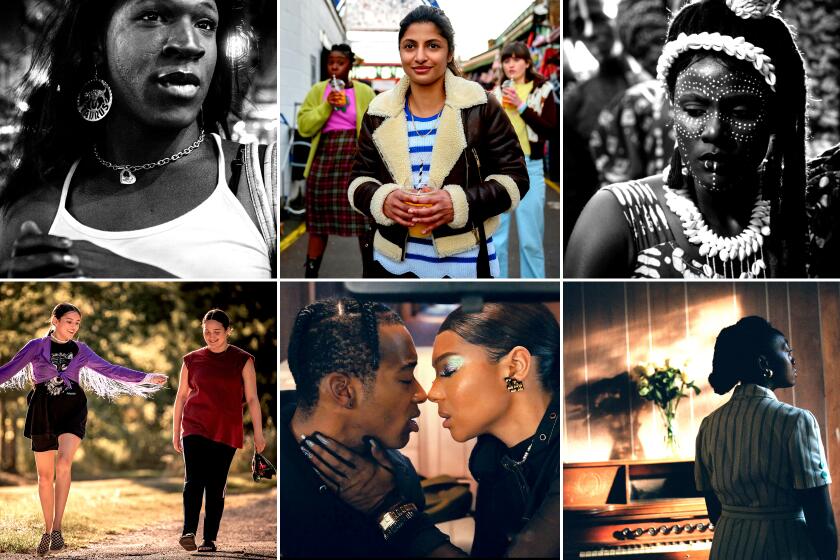

Back in 1998, the Sundance prize went to two documentaries, Garbus’ “The Farm” and Todd Phillips’ “Frat House.” Twenty-two years later, Garbus is back at the film festival with her first narrative movie, “Lost Girls,” a Netflix drama about a mother searching for her daughter who goes missing in Long Island, N.Y., after falling into the world of online sex work. A few weeks after her movie’s premiere, Phillips has a chance at taking home three Oscars at the Academy Awards for his work as director, cowriter and producer of the blockbuster hit “Joker.”

“I don’t know Todd’s trajectory, and if he tried to make more docs,” said Garbus. “But I had a script I was carrying around in my pocket for a long time after ‘The Farm’ that I couldn’t get made. So why are there more female documentary filmmakers? Because the pay is less. The threshold for entry is less. The budgets are less. I don’t think women are inherently better documentary filmmakers.”

Garbus is one of two critically acclaimed female documentary filmmakers transitioning into the fiction genre at Sundance this year. The other is Heidi Ewing, whose narrative debut, “I Carry You With Me,” was acquired by Sony Pictures Classics five days into the festival. Based on the story of her two longtime friends, the Spanish-language film follows two young Mexican men who struggle to keep their romance alive as they illegally cross the U.S. border. Ewing and her creative partner, Rachel Grady — best known for their Oscar-nominated 2006 documentary “Jesus Camp” — also have another project at Sundance: the Showtime docuseries “Love Fraud,” which will air in May, about a group of women who are conned by the same man on an online dating site.

In separate conversations, Garbus and Ewing — who are well-acquainted through the film world — spoke about the challenge of segueing into the narrative moviemaking.

When you started your career, did you aspire to make fiction or nonfiction films?

Ewing: Some documentary filmmakers look at it as a stepping stone to narrative work. I wasn’t ever looking to do a narrative, and that does limit the kind of stories I can tell.

Garbus: As an undergrad, I actually made documentaries and narrative films. But out of college, I ended up being an intern at Miramax, and that wasn’t very exciting. So I got hired by Jonathan Stack, and working with him on documentary allowed me to direct a film when I was 25 because there was much less money needed.

But you can’t separate out all the factors that go into one’s evolution. After “The Farm” did well, I ended up getting my next doc financed, which was amazing. [HBO documentary films president] Sheila Nevins wanted to talk to me, and she was giving me development deals. So I wasn’t sitting around discouraged that I couldn’t get my scripted film made. And I was doggedly pursuing many docs all the time, somewhat voraciously, so maybe I didn’t leave myself enough time to hustle on scripted projects.

Why make your directorial debuts in the narrative space now?

Ewing: I was at Sundance eight years ago, and my friends Ivan and Gerardo told me the story of how they met. It impacted me so greatly, but there were three to four eras in the film, and I thought it needed a more epic trajectory — a narrative treatment to be its own self. It was never really my intention to make a narrative film, but now that I’ve done it, I’d like to do another one.

Garbus: There had been other scripted films I was trying to get made, some of which were harder to get off the ground. But when I read the script for “Lost Girls,” it was the one that felt like the immense boulder I was going to push over the hill. There was a strong female protagonist that really spoke to me that I felt I could sink my teeth into. Some of the women I’d made documentaries about, like Nina Simone, were strong, complicated world-changers. So I felt like I knew who this character was.

I had never completely set aside the idea of making a scripted film, but when my children were little, I was probably just more focused on docs. I thought: “Maybe this isn’t the best time for me to mount something new and different.” And now that they’re older, I have the bandwidth.

How difficult was it to get these movies made?

Ewing: I had to really talk people through what I was doing. It’s a very unconventional narrative, so there was some skepticism. But I can’t say I encountered more resistance than in the documentary space. I think that curiosity helped me get the funding. But I took many, many meetings for the film and there was maybe, like, one woman I ever met. I was always the only woman. And that had not happened to me in documentary. It took me off guard. A lot of the financing for documentary comes through Netflix or Showtime or other television entities, and there’s a lot of women in that space. But I don’t feel like I was penalized in any way [for being a woman], and a lot of men helped get this movie made.

Garbus: I made the first original documentary for Netflix, “What Happened, Miss Simone?” It was only a few years ago, but the company was really so much smaller. So Ted Sarandos and everyone was very involved in every aspect, and Netflix embraced and supported me and gave me an opportunity that had been harder to come by in the business. I had many, many films for HBO, but I think that kind of crossover potential was appreciated at Netflix.

How do you think your background in nonfiction helped you on set?

Ewing: I know when something feels fake. I can tell when dialogue sounds fake, even if I wrote it. I would say to the actor: “I can tell it’s not coming out. Why doesn’t it feel right? How would you rather say it?” And we would talk about it until it felt natural. That ear — that’s been honed over time for that realism.

I also think my background led me to always be stealing a moment. I had an agile cinematographer and I’d say, “The sun looks amazing, let’s grab the actor and shoot this.” A lot of DPs in fiction would not be down for that, because they don’t want to use stuff that’s too loose.

Garbus: There is a similar skill set in working with doc subjects and actors. You’re trying to make someone feel as comfortable as they can to do their best. In a doc setting, you’re working to make someone comfortable to help them find their truth, and that’s kind of what you’re doing with actors too, once you both understand the truth of what the character is in that moment.

You both relied on your nonfiction backgrounds with these films — Heidi, your project is based on your friends’ real-life story and Liz, yours on a 2013 true-crime book.

Ewing: I adhered very closely to the true story. I would get stuck on the script and go back to the transcript of interviews and recordings to look for help to get out of a scene. I would call my friends and say, “Tell me about that bar again. Was it dark? Were there candles? How clandestine was it?” The writing experience is lonely, awful and horrible — so it was probably a less scary experience because I had them to talk to.

Were there challenges you didn’t anticipate in making a narrative film?

Ewing: It’s such a different method. I think people underplay how different the process is. So much work is done before you start recording: the location scouting, the writing, the rehearsals. That was strange for me. There’s something about knowing if you don’t get the shot, you’re in trouble, that I wasn’t used to. There’s something intense about it, and you have to be more precise, in some ways. It makes you crystallize your vision on location [more] than in documentary, where a lot of times your vision is more crystallized in the edit.

Garbus: It definitely takes some getting used to the glacial pace of a larger production crew. With a doc, you’re only working with a few people, and you’re ready to jump and roll and seize any moment.

Were there parts of the process that you found more enjoyable?

Ewing: The truth is, there is no excuse to have one ugly shot if you’re making a scripted film. In documentary, sometimes you’re running, you’re gunning, and someone tells you to turn off the camera. But having the ability to create a color palette and think through the focal length — to be able to shot list and see my options — that was so pleasurable. I didn’t want to squander any shots.

Garbus: It’s a beautiful thing when you come together and have the production meeting and each department head is a visionary in their own right, and you’re the conductor of this orchestra. I love seeing that talent come together. You don’t have that on a doc, because it’s so small and intimate.

Heidi, you’re a white woman telling a story of two Mexican men. Is that why you brought on screenwriter Alan Page Arriaga to cowrite the project with you?

Ewing: Yes. That was something I was very cognizant of, and there was a constant self-policing — or maybe that’s too strong of a word — just checking in. On one hand, this wasn’t going to get told unless I told it. On the other, I’m from Detroit. Alan is Mexican-American and has lived in both countries. I asked my actors and my crew to help me get this right. I said: “I am not from here, and I am leaning on you.” I was in their hands in so many ways. And everybody took that message from me very seriously and took the movie as their own. I’m really proud of that, because they tell me it feels like a Mexican film to them.

Do you want to keep toggling between both genres?

Garbus: I would definitely like to do this again. I learned so much, and I really loved the experience I had on set. But I’m making a doc now. You have to fall in love with a scripted project. It has to be something you’re absolutely devoted to, because it’s such a long, hard process.

I am not complaining about my career. I don’t want to make “The Hangover” — or I don’t think I do. It would have been a very different film if I made it. But there is something there for all of us to think about — what filmmakers are ready for next. I think that people look at male directors and say, “Oh, he did that — let’s throw him into a bigger ring and see what happens.” With a woman, it’s like, “Oh, she did this — maybe she can do this kind of thing again.” I think there’s the belief of possibility in a male director that is still circumscribed when that person is a woman.

Ewing: Why not try to pursue both? It’s so hard not to be pigeonholed in one camp or the other. Liz and I came up together, and we have always exchanged tips. We were texting each other from production on these films, and it was really fun. The sisterhood thing is super strong in the doc space. We are always exchanging budget numbers and tips on different network executives. With low budgets, women have always been allowed in. It’s like: “Low budget? Nothing at stake? Let the ladies in!” But a funny thing happened on the way to 2020: Making docs is lucrative now. And we were already here. They can’t kick us out. Take a number, y’all, we’ve been here for a while.

More to Read

Only good movies

Get the Indie Focus newsletter, Mark Olsen's weekly guide to the world of cinema.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.