I see bands at germy, jam-packed clubs for a living. I never realized how lucky I was

- Share via

Going to see a band called the Rapture, I finally decided, felt just a little too much like tempting fate.

A week ago — you remember, back when we had basketball games and elementary school and grocery stores with toilet paper on the shelf — I’d been looking forward to catching a show at the El Rey by the recently reactivated disco-punk group that goes by that rather foreboding name. It would’ve been one of several gigs I took in last week as part of my work as The Times’ pop critic — a job that requires experiencing as much music as possible in as many different circumstances as possible: listening to records, watching TikTok videos, standing shoulder-to-shoulder with other humans inside a crowded club.

For the record:

1:58 p.m. March 18, 2020An earlier version of this post misstated Columbia University infectious disease specialist Dr. Daniel Griffin’s first name as David.

But that was before the coronavirus pandemic took on something of an end-times vibe.

Not 24 hours after I watched another band, Tame Impala, entertain an arena full of people at the Forum, the news about this global medical emergency seemed to turn a corner when Tom Hanks revealed he’d tested positive for the disease and the NBA announced it was suspending its season.

Suddenly, I found myself less than eager to share the same air with several hundred Rapture fans — a moot point, as it turned out, since the El Rey called off the concert a couple of hours before the group was due to go on. It was just one of countless shows, tours and festivals that have been scrapped or postponed — including South by Southwest, Coachella and Stagecoach — at the direction of public health officials who’ve warned against large gatherings.

Coachella, SXSW, “Hamilton,” the next “Fast and Furious” movie and even Disneyland have been affected by the coronavirus. But wait — there’s more.

“Unfortunately, [concerts] will be big spreading events” for the virus, Dr. Daniel Griffin, an infectious disease specialist at Columbia University, told Rolling Stone shortly before music’s two biggest promoters, Live Nation and AEG, pulled their tours off the road through the end of March at the earliest. On Sunday, Mayor Eric Garcetti ordered the closing of bars and nightclubs in Los Angeles, and the CDC advised people not to congregate in groups of 50 or more for the next eight weeks; soon after that came the virtual lockdown of mega-cities including L.A., San Francisco and New York.

Necessary though they may be, the mass cancellations are certain to do serious economic damage to the music industry, not to mention the bartenders and Uber drivers and street-corner hot dog chefs who rely on concertgoers for their livelihood.

But the costs are not just economic. I know I’m not the only one lamenting the emotional and intellectual downsides of a month (or more) without live music.

For me, a performance can often be more valuable than a recording in trying to figure out an artist — to understand how their music works and what type of connection they seek with their listeners. Think of all the information to be had: the songs, sure, but also the clothes, the facial expressions, the choreography, the banter. A great show represents the meeting of art and science, routine and theater; it’s where plans are tested or undone, impressions shaken or solidified.

I remember a night in March 2009 when I saw Prince play three gigs at three separate venues at L.A. Live. The evening was meant to promote a new triple album, but it also revealed the taxonomical streak of a famously genre-blurring legend, with one show for polished R&B, one for down-and-dirty rock and one for slinky hotel jazz.

Artists transform their songs in concert, demonstrating what they think they got wrong in the studio; they claim other artists’ songs for themselves, demonstrating what they think somebody else got wrong in the studio. Headlining the Hollywood Bowl in 2014, Barry Gibb sang a haunting rendition of Bruce Springsteen’s “I’m on Fire” that as a memory I still prefer over the Boss’ original.

A performance can showcase the breadth of a musician’s creative vision, as when Beyoncé blew minds at Coachella a few years ago. And a performance can illuminate a musician’s sense of the demands of tradition: Never was I clearer about how lightly One Direction wore its identity as a boy band than in the numerous times I witnessed the group’s members goofing around onstage in some gigantic stadium or another.

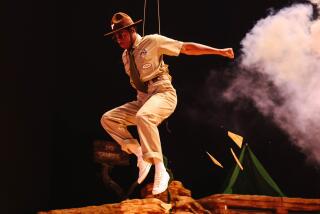

Streaming services, as they’ll no doubt remind us in the weeks of self-isolation to come, are well stocked with content that captures some of what I’m describing here. You can watch classic concert movies like Talking Heads’ “Stop Making Sense” and the Band’s “The Last Waltz,” each essential to understanding its subject; you can trawl YouTube for shaky fan-cam clips from shows you may have gone to in the past five or six years. (Behold my favorite moment from one of those 1D gigs, in which Harry Styles takes an epic onstage tumble.)

There are even companies that allow performers to put on intimate live-streamed gigs for fans who’ve paid actual money to virtually attend.

But nothing safely available on your TV or laptop can compare to being in the rooms we’re now regarding as places of risk. Music just feels different — and I do mean feels — when it’s happening right in front of you, as is well known by anyone who’s put Public Enemy’s bass in their face or had their ears scoured by the guitars of My Bloody Valentine. And there’s no way for those sensations to survive the grim reality of social distancing.

The latest updates from our reporters in California and around the world

I’ve relived Beychella on YouTube and in the Netflix documentary about the concert; I’m grateful we have a detailed record of a brilliant and heartfelt production the singer so obviously designed with preservation in mind. What I recall most vividly about that night in the desert, though, is the palpable awe that swept through the audience as we came to grasp, song by song, the fullness of what Beyoncé was doing in her tribute to America’s historically black colleges and universities. That togetherness, especially in an era when too many of us spend too much of our time behind the walls of the internet, was its own reward.

Are we likely to miss out on an experience as heavy as that one while COVID-19 keeps us all at home? Maybe not — although I had high hopes for Frank Ocean’s (now delayed) Coachella set, his first scheduled performance around these parts since a 2017 appearance at FYF Fest that similarly established a community in a parking lot packed with strangers.

Then again, part of what makes this temporary shutdown such a blow is that it’s depriving us not only of event moments but of the everyday glories that give live music its life. A few nights before the Rapture was preempted by the apocalypse, I caught a thoroughly charming gig by Beach Bunny at the Roxy, where the smart Chicago fuzz-pop band set off what might’ve been the most good-natured mosh pit I’ve ever seen.

As dozens of teenagers happily crashed into one anothers’ bodies, a woman in front of me lifted her phone above her head to snap some photos of the melee; later, I saw her showing them to a girl I took to be her daughter and two of the girl’s friends, all of them gleaming with sweaty post-mosh excitement.

They couldn’t have known it then, but those pictures grabbed a bit of what feels, at least for now, like history.

More to Read

The biggest entertainment stories

Get our big stories about Hollywood, film, television, music, arts, culture and more right in your inbox as soon as they publish.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.