Live music is back, but for roadies and crews, the pandemic’s toll may be irreversible

- Share via

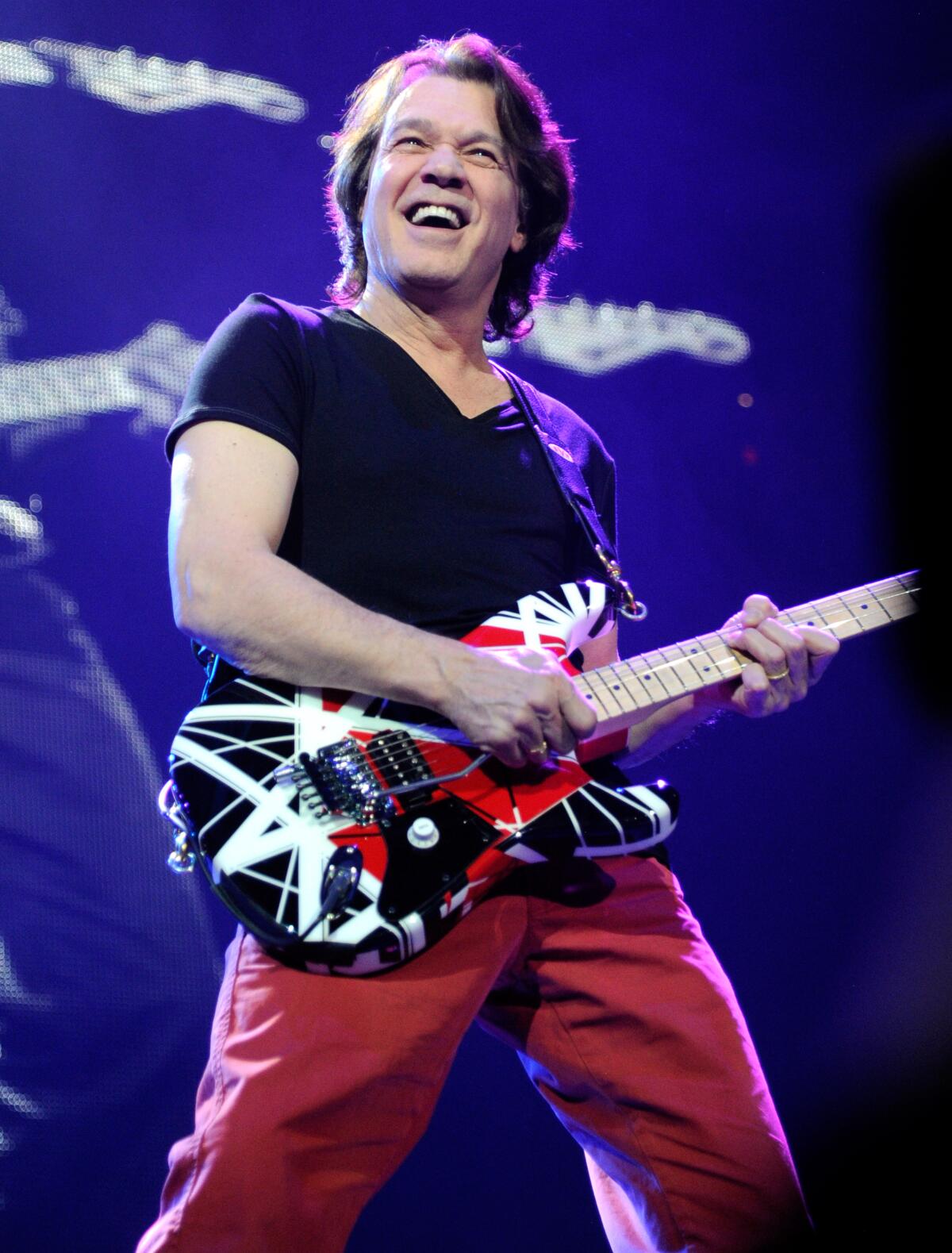

Tom Weber’s job was to take care of the most famous electric guitar in rock ‘n’ roll.

Since 2006, Weber, 63, was Eddie Van Halen’s personal guitar tech, tending to the hard-rock titan’s red, white and black “Frankenstrat,” which sired the riffs to “Eruption,” “Runnin’ With the Devil” and “Panama,” among countless classic headbangers. The Kentucky-based Weber kept it humming through the band’s final tour in 2015, and worked with Eddie until his death last October. Weber had big gigs lined up for Reba McEntire and Journey that year, and a planned run of stadium shows with Poison, Mötley Crüe and Def Leppard.

Fifteen months into the pandemic, though, Weber hasn’t found any significant work — in guitars or otherwise — to tide him over. He admits that he’s soon likely to lose his home, his guitar repair shop and everything he’s built over decades in rock without consistent tours to return to.

“I put my house into forbearance because there’s no way we’re going back to work soon,” Weber said. “No one is hiring a 63-year-old guitar tech after this. I know people who have killed themselves, who are losing homes, families, everything. I’ve heard colleagues say that with life insurance, they’re more valuable to their families dead than alive.”

On his mesmerizing new album, ‘Changephobia,’ former Vampire Weekend member Rostam channels everything from bebop to Bruce Springsteen.

As festivals and concerts return in fits and starts, fans might be forgiven for thinking that things are getting back to normal. Iconic venues like the Hollywood Bowl and Greek Theatre have announced summer schedules; California festivals like Coachella, Hard Summer and Rolling Loud have set dates for this year or early 2022. Even L.A. nightclubs, one of the first sectors to go dark as COVID-19 hit, will more fully open back up along with the rest of the state’s businesses on Tuesday.

But for the people who make their living on or from the road in the touring industry — from tour managers to lighting and sound engineers to truck drivers, stage riggers and merch sellers — “normal” is still a distant fantasy.

“I don’t know even what a ‘new normal’ is,” said Sandy Espinoza, the L.A.-based founder of the tour crew mutual-aid group Roadiecare. “People would go back to work tomorrow if they could, but there’s no more than dribbles of work. We’re all going to have to keep scrambling.”

The pandemic continues to rip across the globe. Between the U.S.’ patchwork of local reopening policies, cross-country travel seized by fears of new variants and complex logistics that make tours difficult to plan months in advance today, many pros are uncertain about when they’ll get back to sustainable work. That, in turn, makes a return to live concerts more difficult for artists — if you can’t hire crew, there’s no show.

Some pros like Weber fear that a stable career on a tour bus might not be viable for a long time. Some of them have left the business, but others are desperate to work despite the uncertainties.

“You’d think, ‘Who wouldn’t want to hire Eddie Van Halen’s guitar tech?’” Weber said. “Well, I even filled out an application to drive the Oscar Mayer Wienermobile but they said I needed a bachelor’s degree. We’re the Marine Corps of the entertainment industry; no one knows better than us that the show must go on, but now we’re the ones in trouble and no one seems to know we exist.”

As summer concerts resume, those worries are widely shared in the touring industry, all the way up to arena-sized tours.

Todd Bunch is the tour manager for country superstar Eric Church, who has a run of North American arena dates planned for the summer and fall.

“The business was hit tremendously,” he said. “The industry lost so many good employees and techs and musicians who had to flee or fight to survive, or took their own lives. I lost four friends or acquaintances this year.”

As part of our Column One story on Kevin Howard’s struggle to build a life beyond the battlefield, here is a list of organizations that provide support, information and resources to veterans and others.

Even a fitful return to the road feels like “light at the end of a tunnel, happiness where it was dark,” Bunch said. “Eric took great care of us, but we all had to check on our friends after we saw so many lives lost or taken. Industrywide, a lot of people just weren’t thinking about gig workers, and a lot of people feel slighted. Some just won’t come back.”

“People are going back to work, but in the scheme of things, it’s really just outdoor fests right now,” said Jerome Crooks, the tour manager for Tool and Nine Inch Nails. “A handful of shows does give crew something to look forward to, but it’s not the business it used to be. A lot of people went out and got day jobs. I hear lot of people saying, ‘Hey, I got a job with Amazon with benefits and I can look after my kids.’”

Crooks cited the charity work of organizations like MusiCares, Just a Bunch of Roadies and the Touring Professionals Alliance, with whom he’s worked to steer meals, mental health services and health insurance to out-of-work crews. Mega-promoter Live Nation founded a charity network, Crew Nation, to distribute small grants to furloughed roadies (it’s hosting a job fair at the Hollywood Palladium on Sunday).

Timeline of a comeback: historic cancellation of an entire season, painful layoffs, transformation into a recording studio, a whirlwind race to reopen.

Typically, such work is seasonal but well paid, from $10,000 a month into six figures for a summer-long tour for a major act. Some portions of tour staffs (which can run up to 150 people for arena acts like the Rolling Stones) remained salaried while off the road. But most crew are non-unionized, without health benefits and typically bounce between tours.

For those laid-off roadies, techs and tour managers, surviving the last year has meant stitching together a living from unemployment, charity and whisper-networks of jobs from peers.

“It’s been way too easy to sit at home and stress,” said Geoff Bruce, 52, the longtime drum tech for the metal band Testament and a sound engineer at the Whisky a Go Go in West Hollywood. “It’s lean, man. All the side jobs were just inundated, everybody applied to be a delivery driver. I called so many places that said, ‘We’ll put you on the list.’”

Bruce said he’d barely made ends meet in 2020. “I applied for my real estate license, I did a course for COVID contract tracing, moved some stuff for friends. It’s been daunting.”

“I’m always a preparer, but I ended up with so much anxiety I was panicking,” said Hossein Attar, 50, a tour manager who has worked with acts including Michael Franti and Jacob Banks. Attar turned to rental property management to survive the pandemic, and admits to growing disillusioned with the music industry over the last year.

“At first, a lot of guys were panicking about where they’re going to live,” said Attar. “Now, they may get a call from an artist asking if they want to do three shows at Red Rocks, but do they want to give up their unemployment or their day job to get that little check?”

“Festival dates are fine, but it’s awkward for crew because that isn’t enough work to downshift from whatever they’ve been doing for months,” said Jason Bell, 50, the San Francisco-based tour manager for folk legend Billy Bragg. Bell has been living off savings and stray handyman work around the Bay Area. “Things need to come back to a level where people can afford to stop doing what they’ve been doing for a year.”

While the worst of the pandemic may have subsided in California, it’s still very much on the minds of tour pros for whom going back to work means, night after night, interacting with tens of thousands of people across state lines, often in regions that have been more cavalier about the virus.

“I’ve got a daughter with a heart condition and an autoimmune disease. We’re vaccinated but I don’t know how she’d be affected by COVID. My grandmother died from it,” said Daniel O’Neil, 51, a Nashville-based backline crew chief who has worked with Matchbox 20, Slayer and Cyndi Lauper. “I need to see cases down and protocols in place out of for respect for my daughter and myself.”

He’s drained his 401(k) to survive, but going back to partial, risky work might be worse than staying the course and getting his real-estate license, he said.

“Everyone sees ‘tours’ going out, but they’re not. It’s a couple weeks or weekend-warrior stuff,” he said. “A band can’t break even on a sporadic tour when they have a show in Florida and the next night’s in Texas. I can’t tell you that I’ll be back.”

While the primary worry is with struggling crew, the industry is beginning to discover how much of the infrastructure of touring has been reallocated, gone out of business or snatched up by acts trying to hit the road at once. Decades-old backline rental companies like Studio Instrument Rentals are whiplashed between zero demand and a flood of it; several tour managers cited a recent run on drivers, sleeper buses and trucks that companies scrambled to offload at the beginning of the pandemic.

“It’s a big question of who is able to come back, and how many of these changes in the industry are permanent,” said Joel Eriksson, the production manager for Shania Twain’s Las Vegas residency. “A lot of vendors haven’t confirmed who they’re able to send. Truckers were obviously needed elsewhere than rock ‘n’ roll.”

“The lighting vendors, the sound engineers, the video and trucking companies, they have real challenges right now,” Crooks agreed.

Espinoza, a 30-year tour veteran, founded Roadiecare just days into the pandemic to distribute food aid and generally serve as a last line of defense for crew spiraling into despair. The work has only escalated over the last year.

“I answered one middle-of-the-night call where a lighting director was sobbing that he had to put his kids to bed hungry,” she said. “He had no unemployment, no food bank nearby, and he felt so guilty. We got him some aid to buy some basics. He’d lost his tour, his job and his marriage.”

She’s pessimistic that touring as a career will be viable for crew until well into next year. Many colleagues are facing the end of extended unemployment benefits (if they were able to get them at all). She said many gig workers in touring feel left out of legislation like Save Our Stages, meant to rescue independent venues.

“It’s been absolutely disgraceful that the government has completely forgotten us,” Espinoza said.

Some hope to come back to a better industry. Noelle Scaggs, co-lead vocalist in the L.A. pop group Fitz and the Tantrums, founded the group Diversify the Stage to bring more minorities into typically white and male tour crews. The pandemic has been a violent reset, she said, but potentially a chance to change the business.

“We have to think beyond right now,” Scaggs said. “There are opportunities to bring in new folks. We can make asks about how we operate, we can figure out what were obstacles and work towards changing them. We want all artists to stand together on this, because I want to widen the net of opportunity, and I don’t want to spend another year off the road.”

Nashville’s O’Neil, for one, plans on being back in music venues one way or another this year.

“The minute I’m homeless, I’ll find a venue that got funding and I’m moving in,” he laughed, grimly. “I know plenty of places to sleep in the Ryman Auditorium.”

More to Read

The biggest entertainment stories

Get our big stories about Hollywood, film, television, music, arts, culture and more right in your inbox as soon as they publish.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.