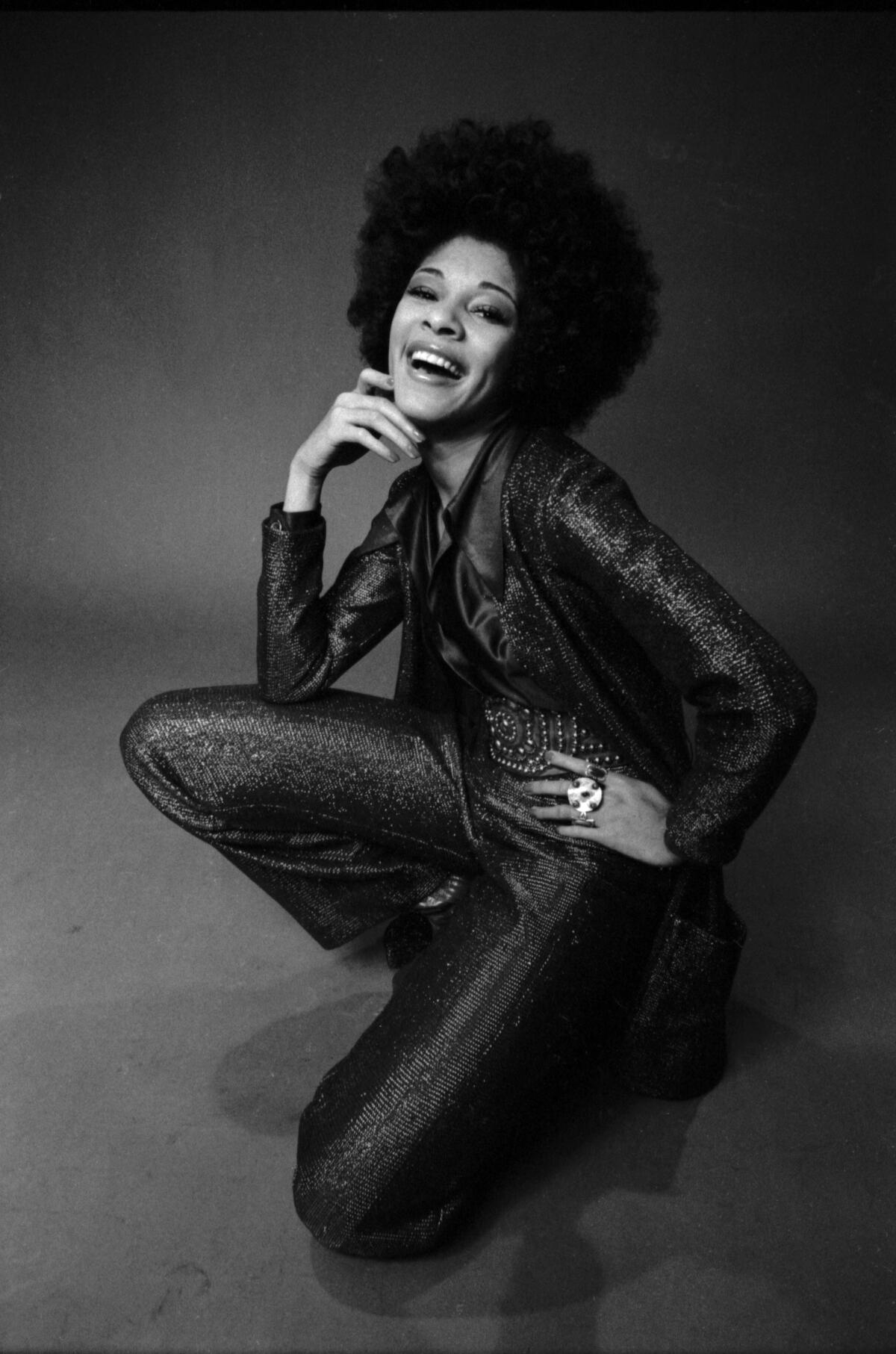

Betty Davis, funk pioneer and former wife of Miles Davis, dies at 77

- Share via

Singer, songwriter, producer and style icon Betty Davis, whose unfiltered, in-your-face 1970s funk songs including “He Was a Big Freak,” “Game Is My Middle Name” and “Nasty Gal” conveyed a brash power that broke gender barriers and defied male-dominated sexual mores, died on Wednesday. She was 77.

Davis’ death, of natural causes, was announced by her longtime reissue label, Light in the Attic Records.

Despite possessing the allure of a fashion model and the unbridled emotion of a rock star, Davis never had a hit record, but her three long-players between 1973 and 1975 are now considered classics of the era.

As a young girl, country singer Mickey Guyton felt ‘proud to be an American’ after hearing Whitney Houston’s Super Bowl rendition of ‘The Star-Spangled Banner.’

“The reach of her influence & sonic lineage is immense,” wrote author and critic Hanif Abdurraqib on Twitter. “You’ve heard her, even if you think you’ve never heard her. I’m glad we got her at all.” Davis’ work earned a second life through samples on records by artists including Method Man, Ice Cube and Redman.

They were no doubt drawn to her skills as a funk songwriter, producer and bandleader, as well as her certainty that she possessed the musical and sexual energy to conquer whatever man might attempt to tame her. “Don’t you answer your phone,” she commanded a lover on 1975’s “Shut Off the Light.” “Just let it ring — just shut off the light.”

Her charisma drew the attention of both Jimi Hendrix and Miles Davis, the latter of whom she married in 1968. Her music, though mostly ignored when it was released, earned renewed praise when her three solo albums and previously unreleased fourth one were reissued in the 2000s.

That she quit the business just as she seemed to be getting started remains one of the great what-if stories of funk and soul music.

Betty stopped recording music altogether after releasing her third album, “Nasty Girl,” in 1975. Retiring from the business Greta Garbo-style, she shuttered herself from the public until a mid-2000s groundswell of writers and fans began touting her work anew.

Born Betty Mabry in Durham, N.C., and raised there and in Pittsburgh, she moved to New York City at 16 and attended the Fashion Institute of Technology. At nights, she worked at a hip club at 90th Street and Broadway called the Cellar, where she curated the music, hired the club’s dancers and served as emcee. She also started making music, and in 1964 released a single called “Get Ready for Betty.”

She was born into gritty music, as she explained in the lyrics to one of her best known songs, “They Say I’m Different”: “My great grandma didn’t like the foxtrot / Nah, instead she’d spit her snuff and boogie to Elmore James.”

Though “Get Ready for Betty” failed to chart, she had another income source: Her striking looks drew the attention of a prominent modeling agency, which allowed her to keep up on fashion while working on songwriting and music in her downtime. She earned her first musical success when the psychedelic soul band the Chambers Brothers recorded her song “Uptown” on their 1967 debut album, “The Time Has Come.”

She met Davis while he was was also involved with Cecily Tyson — and not yet divorced from his first wife, Frances Taylor Davis. Though Miles was twice Betty’s age, the connection was quick. “She was just ahead of her time,” Miles wrote in his autobiography. “She also helped me change the way I was dressing. The marriage only lasted about a year, but that year was full of new things and surprises and helped point the way I was to go, both in my music and, in some ways, my lifestyle.”

Jazz fans might recognize her from the cover of his 1969 album “Filles de Kilimanjaro.” The album also features a Miles-penned ode to Betty, “Mademoiselle Mabry (Miss Mabry).”

Both during and after their marriage ended in 1969, Betty Davis was wooed by labels hoping to capitalize on her brashly sophisticated approach — and pop-culture fame. She resisted signing exploitative deals while focusing on songwriting — and recovering from Miles’ physical abuse. “I started arranging music — that’s how he influenced me,” she told Bustle in a 2018 interview, adding, “I stopped writing while I was married to him.”

That changed, though, after they divorced and she began to process what she had endured.

“I told no one of how Miles was violent,” Betty said in “Betty: They Say I’m Different,” a 2017 documentary about her life. Instead, she said, “I wrote and sung my heart out. Three albums of hard funk. I put everything there.”

“I believe in being taken seriously, not coasting on my husband’s name,” she said in a 1974 press release. Referring to two record moguls, she continued, “I could always have recorded with Clive [Davis] or Ahmet [Ertegun] but I would never truly know if I were being humored because I was Miles’ wife.”

Featuring boastful lyrics about love, lust and heartbreak, a hard rhythm section and a cast of backing musicians that included bassist Merl Saunders, the Pointer Sisters and Sylvester, her self-titled debut record left little doubt who was in control. “You know I could make you crawl,” she sang on 1973’s “Anti Love Song.”

She released that and her follow-up, 1974’s “They Say I’m Different,” through the independent label Just Sunshine, owned by the late Woodstock co-founder Michael Lang. Despite the high-profile co-signs, her music was mostly dismissed by male rock critics. The music-review bible “The Rolling Stone Record Guide” was troubled by Davis’ “unusual sexual posturing,” concluding that “the songs never fail to titillate.”

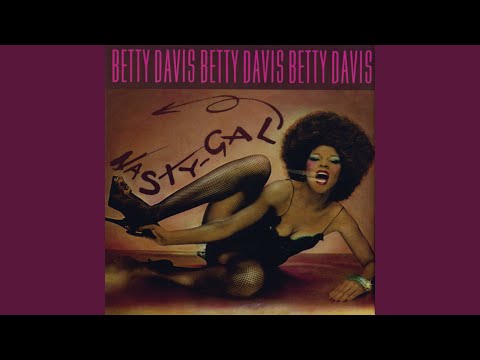

Her response came in “Dedicated to the Press,” from the 1975 Island Records-released “Nasty Gal.” They say I’m vulgar / And some people can do without me / Well, all I can say is it’s such a shame / Why do they blame me for what I am?”

“If you scanned the credits on her albums you realized that Betty wasn’t merely a mouthpiece for a male producer or songwriter but an artist in her own right, an independent visionary in an era where black female solo artists were a rarity,” wrote soul scholar and author Oliver Wang in the liner notes to Light in the Attic’s 2007 reissue of “Betty Davis.” “In a show of independence that has few comparisons, then or now, Betty wrote every song she ever recorded and produced every album after her first.”

She quit shortly after “Nasty Gal” came out, moving back to the Pittsburgh area and leaving her music career behind. In 2007, the Seattle-based reissue label Light in the Attic rereleased her first two albums. The reissues, which helped establish the label as a force in archival recordings, earned Davis praise from new generations of writers and musicians.

In 2009, the label reissued “Nasty Gal” and a previously unreleased 1976 studio album, “Is It Love or Desire?” Though unheard for more than three decades, it further confirmed Davis’ stature — and her signature approach.

Asked to describe that approach in one word during an early interview, she captured its essence with her reply. “I’d just say it was raw.”

More to Read

The biggest entertainment stories

Get our big stories about Hollywood, film, television, music, arts, culture and more right in your inbox as soon as they publish.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.