- Share via

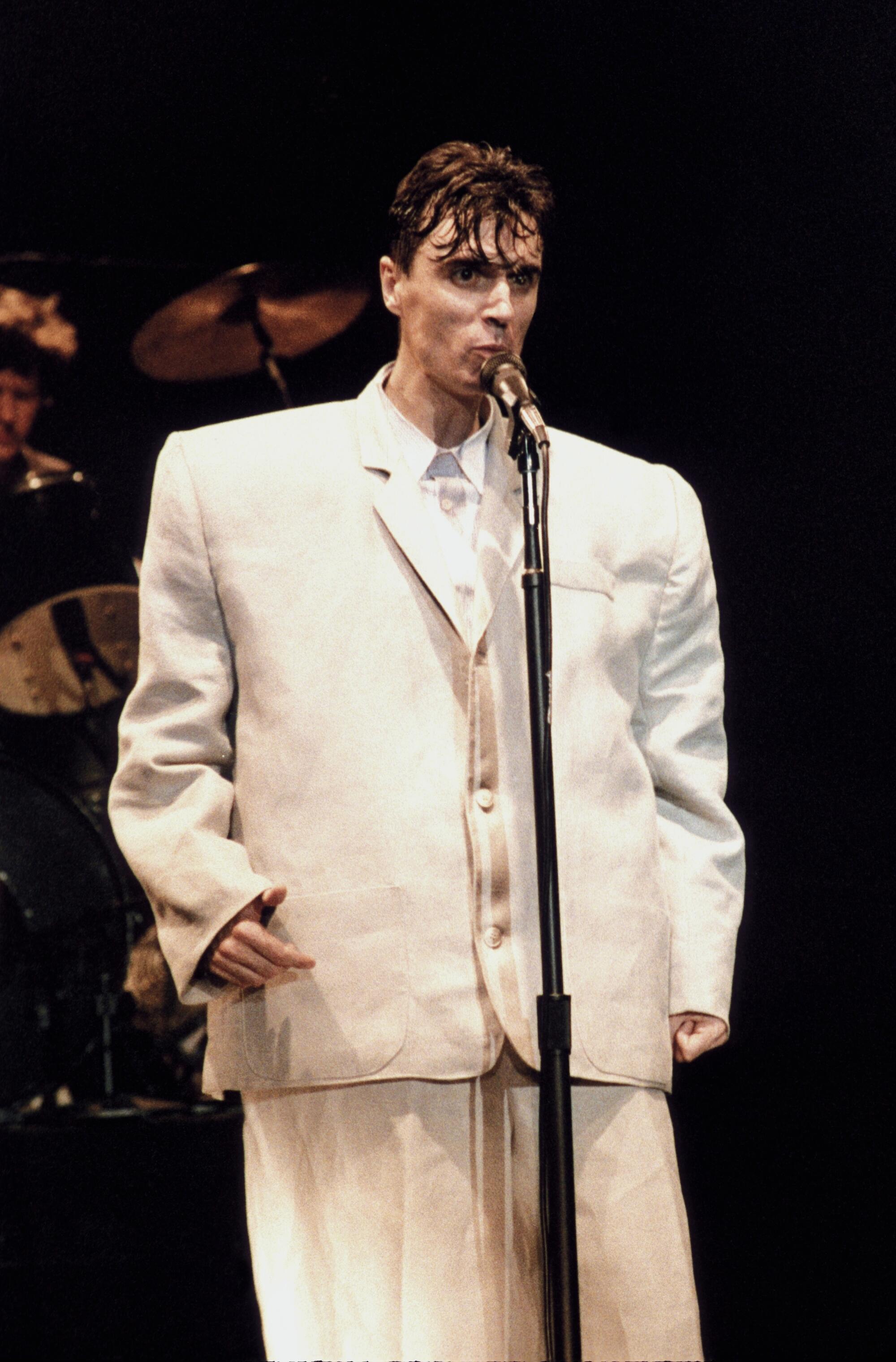

It isn’t often that clothing gets applause from the audience at a music documentary, but “Stop Making Sense” is an unusual and beloved movie that, in the past 40 years, has spawned memes and even skits, mostly about the boxy, comically oversized suit worn by Talking Heads singer David Byrne. So when the movie was shown last week at the Scotiabank Imax Theater during the Toronto International Film Festival, and Byrne came onscreen, partway into the movie, in his iconic Big Suit, the audience erupted.

The title of “best music documentary” is up for endless debate, but it’s hard to dispute that “Stop Making Sense” is the one that’s inspired the most dance parties. (No one dances during “The Last Waltz” screenings.) Even Spike Lee stood up and danced in Toronto when the band played “Once in a Lifetime,” a polyrhythmic, joyful song with the refrain “Same as it ever was.” After the screening, Lee interviewed Talking Heads in a simulcast Q&A and proclaimed, “This is the greatest concert film ever!”

For film lovers, the night marked a new era for “Stop Making Sense,” which is being rereleased by A24, first to Imax theaters on Friday and then widely on Sept. 29, in a restored 4K print made from the original negative. It was filmed at the Hollywood Pantages Theatre in December 1983, and was directed by future Academy Award winner Jonathan Demme, who died in 2017. New Yorker critic Pauline Kael called it “a dose of happiness from beginning to end,” as well as “close to perfection.”

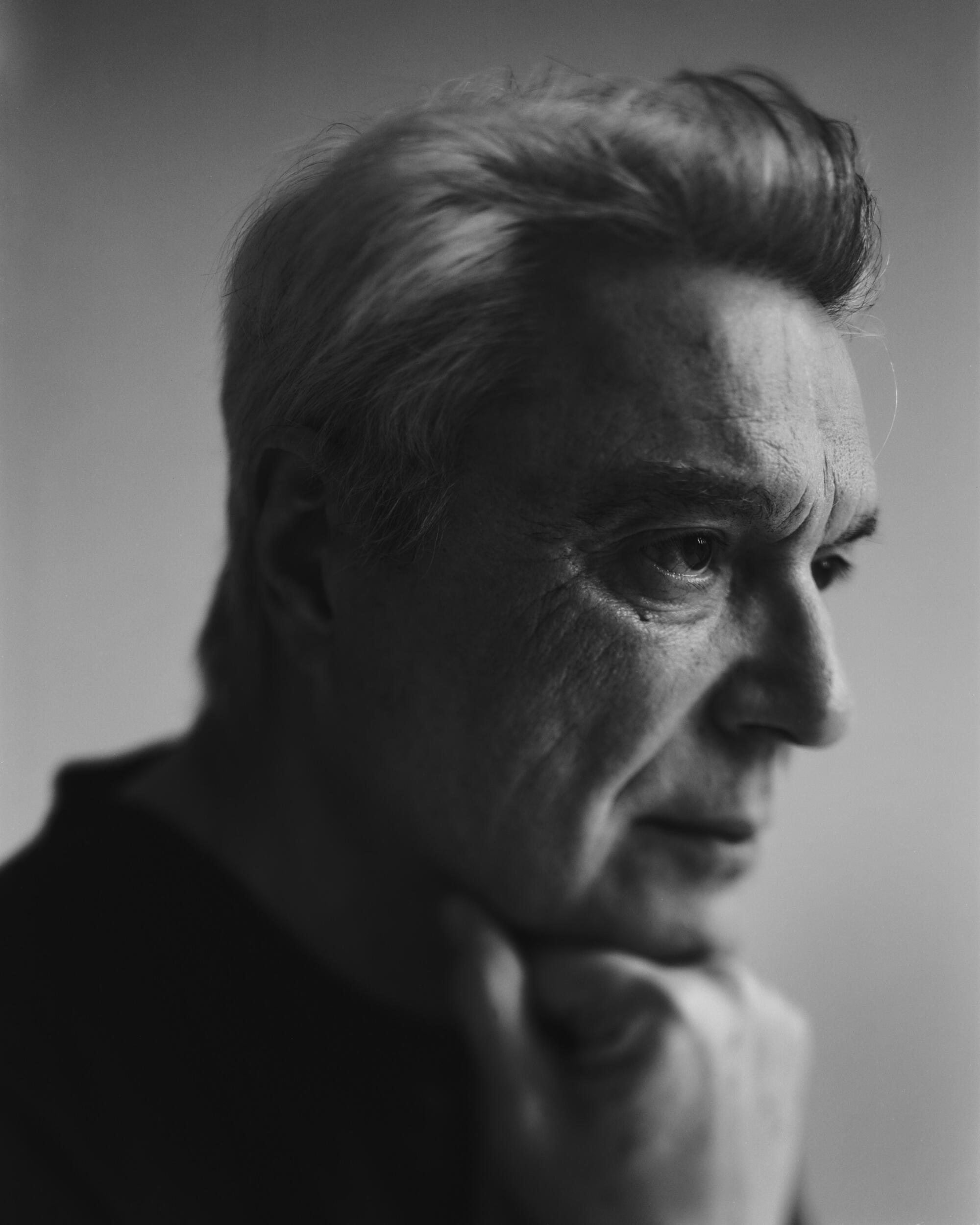

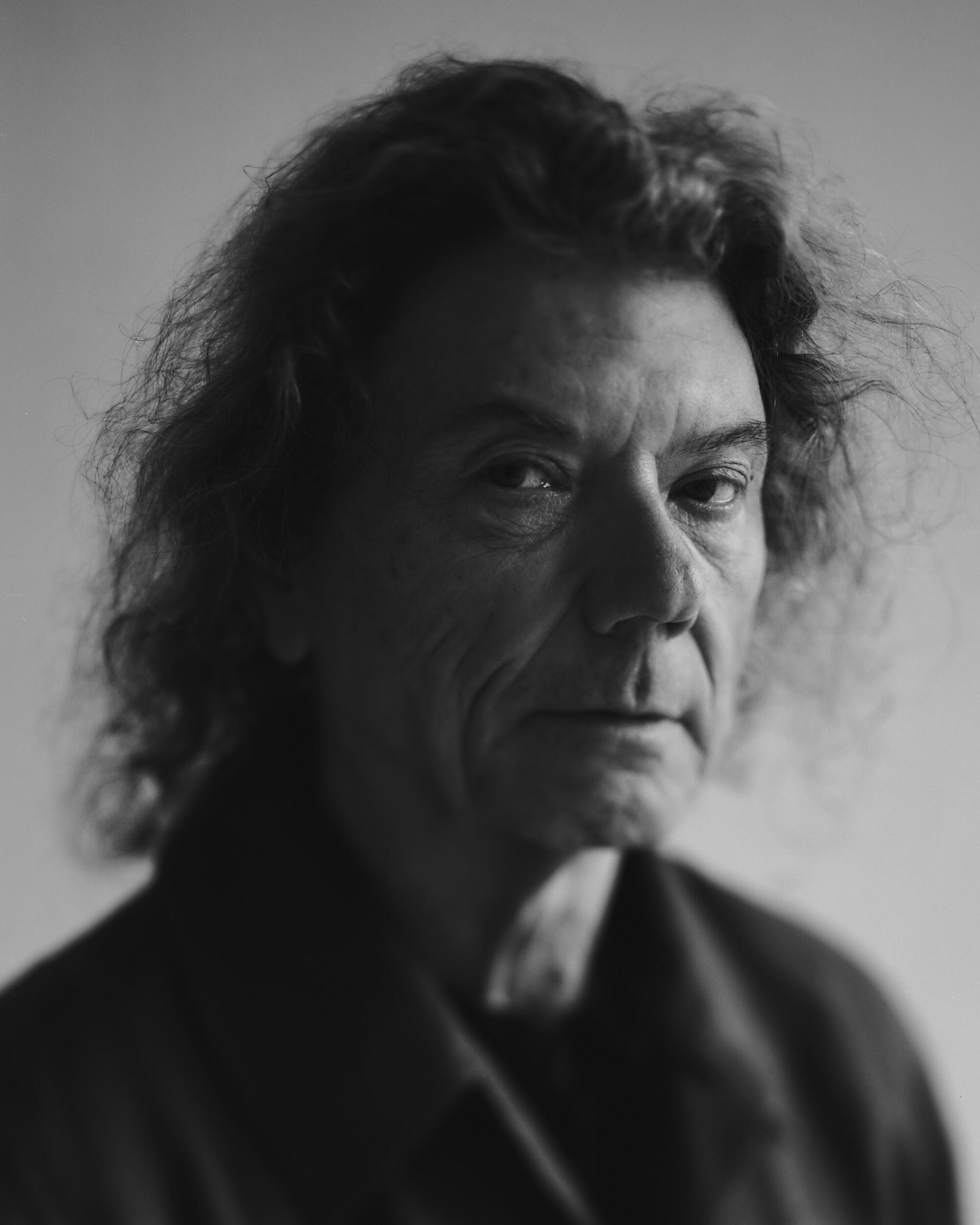

But for music lovers, Toronto was exciting for a parallel reason — it was the first time the four members of Talking Heads (Byrne, 71; drummer Chris Frantz, 72; bassist Tina Weymouth, 72; and guitarist/keyboardist Jerry Harrison, 74) had appeared together since 2002, when they were inducted into the Rock & Roll Hall of Fame.

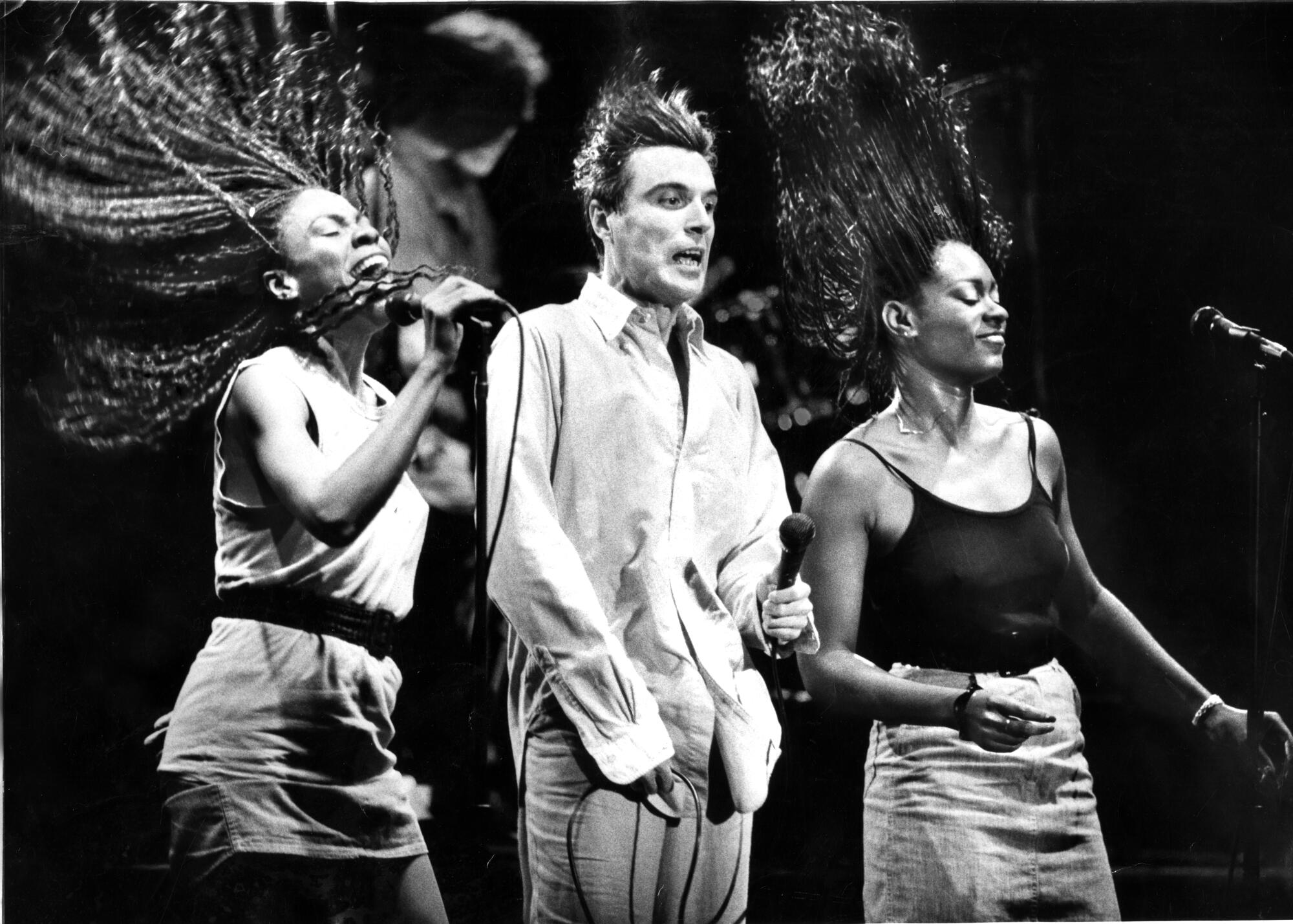

Frantz and Weymouth met Byrne at the Rhode Island School of Design in Providence, and after moving to New York City, they became regulars at CBGB. Talking Heads began with a spare, minimalist sound that deepened into something fraught and funky. By “Stop Making Sense,” the band had added five Black musicians as auxiliary members: guitarist Alex Weir, exuberant percussionist Steve Scales, singers Lynn Mabry and Ednah Holt, and Bernie Worrell, the Thelonious Monk of the synthesizer.

“I was a peculiar young man — borderline Asperger’s, I would guess,” Byrne once wrote on his website. There was a nervous quality to Talking Heads — onstage, Byrne was like Gregory Peck crossed with Edward Scissorhands — but the group’s songs, often about urban anxiety and alienation, creased the pop charts, most notably “Psycho Killer,” “Take Me to the River” and “Burning Down the House.” They were the rare band that translated art-school concepts into genuine pop art.

Talking Heads had stopped touring by the time “Stop Making Sense” was released in 1984, and they made their final album four years later. Byrne’s solo career has included an Oscar, a Grammy and a Tony, multiple albums and the Broadway show “American Utopia,” which was filmed by Lee. Frantz and Weymouth formed the Tom Tom Club, and surpassed Talking Heads’ success with the often-sampled worldwide hit “Genius of Love.” Harrison has made three solo albums and produced numerous records, including Live’s “Throwing Copper,” which has sold 8 million copies.

The breakup was ugly: Among other jibes, Weymouth once said Byrne was “incapable of returning friendship.” Byrne has spent years rebuffing reunion questions, once saying that a reconciliation was “very, very unlikely.” During the Q&A with Lee, the four bandmates were polite, complimentary and deferential. If the band is moving toward some kind of reunion tour, they’re not saying: “Right now, we’re concentrating on ‘Stop Making Sense’ and how much fun we’re having revisiting the film,” Harrison tells The Times. “We’re living in the moment, so that’s all we’re thinking about.”

The four members of Talking Heads appeared onstage for the first time in 21 years for the 4K restoration of their landmark concert film ‘Stop Making Sense’

The bonhomie continued the next day during an hourlong interview with all four in a suite at the Ritz-Carlton Hotel in Toronto, where they discussed the unsung heroes of “Stop Making Sense,” the Big Suit and why it doesn’t appear earlier in the movie, and what lessons they learned from Fred Astaire.

The Toronto screening on Sept. 11 was livestreamed to 165 Imax theaters and broke the previous record for a live Imax event, with a gross of more than $640,000. Once again, Talking Heads are setting off dance parties around the world. It turns out, the best live band of 1983 is also the best live band of 2023. Same as it ever was.

Art-school bands often have an advantage, because they’re comfortable with design and film. Tina, when you, Chris and David were at RISD, was film part of the curriculum?

Tina Weymouth: We didn’t have a film department, but we were friends with a painter named Jamie Dalglish, who insisted the school start one. All I wanted to do was paint, but David was into film early on.

David Byrne: They had film nights at school, where they would show mostly foreign movies, things I’d never come in contact with. It was like the moment when you first hear rock ’n’ roll.

Like seeing the Beatles on Ed Sullivan, for you?

Byrne: Yeah, that kind of moment. Once a week they’d show a Godard movie or a Fellini movie, and you’d go, “Look at this crazy stuff! What the hell is it about?”

In the beginning, what was the band trying to do, in terms of lighting, stage clothes and other parts of your presentation?

Chris Frantz: We moved to New York in ’74, and our look was different from our contemporaries. Take Aerosmith, for example, who I know Jerry was a big fan of [laughs].

Jerry Harrison: They were friends of mine!

Byrne: Or the other bands at CBGB.

Frantz: A lot of bands had lived in New York longer than we had, and had been through the New York Dolls, glam-rock period. We wanted to present ourselves as we are and not dress up like rock gods.

Harrison: For years, our instructions to lighting directors were, “Turn the lights on when we walk onstage, and turn them off when we come off.” I said that when we played Radio City, and they looked at me like I was insane. [laughs] It was so honest — no artifice in our dress, no trying to manipulate the way you see us with lights, just us and our music.

Deconstruction was a big topic at art schools in the 1970s, and early on, you seemed to be deconstructing what it meant to be a band. By “Stop Making Sense,” you’d added costumes and lights but were still deconstructing a live show, by starting with an open, bare stage and then rolling out risers and instruments right in front of the crowd.

Byrne: By the time we got to “Stop Making Sense,” the lighting was still all white, but white light made by different kinds of instruments, whether it was fluorescent or sodium vapor. So it all kind of looks white to the eye, but it has different qualities.

Weymouth: You’re trying to get full spectrum, because we were all different skin colors.

Frantz: Steve Scales said, “Don’t put no green lights on me, man!” [laughs]

Weymouth: When we show the crane shots at the end, it’s great, because as David and Jerry have said, it’s a reveal. You’re showing how the magic gets made.

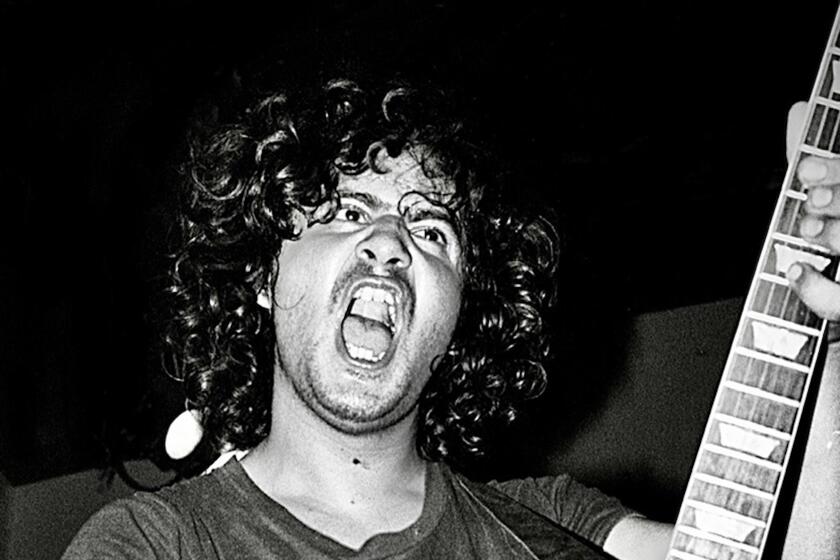

East L.A.’s the Stains, led by wildman guitarist Robert Becerra, were one of the city’s original punk bands. Becerra died from liver cancer on Sept. 1 at age 64.

You played four nights at the Pantages. Did you film all four?

Byrne: We did, but the first night was kind of a wash. There was an idea to put lights over the audience, so you could see them reacting, but it inhibited the crowd. What you got was reverse shots with people sitting there, afraid to move.

In 1983, people weren’t used to being on camera. They are now.

Byrne: Yeah, now it’s like, “Here I am! Look at me!”

Frantz: We did a special performance in 1979 at the Mudd Club for a British TV program, “The South Bank Show.” The Mudd Club was always very dark, but on this night they put super bright lights on us and the audience freaked out.

Weymouth: It’s like turning on the lights for teenagers having sex.

Inevitably, films have hiccups. Jonathan Demme wasn’t available during the daytime, because he was busy reshooting Goldie Hawn for “Swing Shift,” wasn’t he?

Weymouth: Sandy McLeod [credited as visual consultant] made up for the shortfall. She came on tour with us and was like a second director. She took copious notes and mapped out all the shots.

Harrison: There was consternation about Jonathan’s absence, like, What the hell? It created tension. You could feel him being pulled in two directions.

I called up my friend at Warner Bros. to see if they could change the “Swing Shift” shooting schedule, and she said, “What are you talking about? Of course not!”

Another hiccup was that the five auxiliary band members asked for more money, right?

Weymouth: Yes, they were promised that after the movie there’d be another tour, and then we’d bump up their pay. Chris and I didn’t find this out until three or four years ago, but the women musicians weren’t paid the same as the men. And they found out.

Harrison: We had financed this film ourselves, so we were being careful with the money.

Weymouth: And we didn’t charge much for tickets, so there wasn’t a lot of money. Chris and I had a baby, our first child, and needed to bring a nanny. We got another bus, because we didn’t want to disturb the rest of the band. We felt it was on us to make sure the other guys got their sleep.

David, you’ve said the film has a narrative. How would you describe it?

Byrne: There’s a guy who is not that comfortable socially, very anxious and nervous, and he gradually finds community and a way to let go, through music and dancing. He finds a way to be more comfortable, and he finds joy.

He’s liberated by funk?

Byrne: Absolutely, yeah!

Why does the Big Suit not come out earlier in the show?

Weymouth: Yeah! Why not?

Respectfully, it’s the star of the show.

Byrne: It should get special billing.

Weymouth: I thought our music was the star of the show.

Byrne: The Big Suit should ask for more money. [laughs] You can’t bring it out earlier because we’re trying to keep building things. Once it’s out there, what other cards do we have left to play?

Weymouth: It’s part of the narrative. As David said, he starts off as a nerdy, nervous guy, very serious, singing “Psycho Killer,” and later he’s singing all this joyous stuff and he’s got a sense of humor.

The film had some unsung heroes, in addition to Sandy McLeod. What did cinematographer Jordan Cronenweth add?

Byrne: He had done “Blade Runner,” and we all thought, whoa!

Frantz: That was the ultimate, at that time.

Byrne: In those days, you had to rebalance stage lights, so that what the camera saw was what your eyes saw. You had to dim the brighter stuff and bring up some of the darker bits. During the day, Jordan was adjusting the lights for hours, which paid off.

Beverly Emmons, the lighting designer, had worked with avant-garde theater director Robert Wilson. Was she also an unsung hero?

Byrne: We had all seen [Wilson’s direction of Philip Glass’] “Einstein on the Beach” and the lighting was extraordinary. At the beginning of the tour, Beverly helped us decide what lighting instruments we needed.

Harrison: We were lucky enough to live in SoHo when it truly was a coming together of all the arts. If you hung out at Max’s Kansas City, [owner] Mickey Ruskin was much more impressed if Willem de Kooning came in than Mick Jagger. We were somewhat at the tail end of that cross-fertilization. There were fantastically talented people not overly recognized by the rest of the world, because they were ahead of their time. That imbued us with a certain sensibility.

What is the relationship between “Stop Making Sense” and the vocabulary of music videos that started to become formalized after MTV launched in 1981?

Byrne: Jonathan said he didn’t want to make the movie a music video.

Weymouth: Right, he said it was a beautiful concert and he wanted to capture it as it was. Chris and I told Jonathan we wanted to avoid all the clichés, like split-screen shots and things that draw attention to the camera. We wanted the camera to act as a sensitive eye, so that viewers feel like they are in the audience.

Byrne: In Fred Astaire movies, the dance sequences are almost all without any cuts. The camera follows the dancers wherever they go. It’s like, oh, sometimes it’s stronger not to do quick cuts.

Frantz: We were lucky to have Jonathan make the movie with us. But this was before he was a household name, which he became after “Stop Making Sense.” To me, that means Jonathan was very fortunate to hook up with us as well.

Weymouth: Oh, Chris! [laughs]

Frantz: I’m serious! Hold on, he hadn’t made “Philadelphia” or “Something Wild” or “The Silence of the Lambs.” I just thought I’d throw that out there.

I don’t think anyone at the Pantages had more fun than Steve Scales.

Weymouth: [laughs] We used to introduce him by saying, “The star of the movie, Steve Scales!”

Harrison: We gave Steve the freedom to roam. When we expanded the band, we wanted them to not feel like cogs in a machine but important participants.

While we were on tour, as Ernest Hemingway said, we were a movable feast. When we went into a bar, there was a party, even if there wasn’t anybody there.

Weymouth: That was true on the airplane also. One time, we boarded in New York City and [road manager] Matthew Murphy said, “Where’s Bernie?” The stewardesses were pouring champagne for us. Alex Weir said, “I saw him at a bar, drinking a bloody mary.” So he ran to that bar as fast as he could. They were holding the plane for us.

Alex came running back and he’s towing this recalcitrant guy, with the same cropped hair and shades as Bernie. He drags him onto the plane, saying, “Don’t dawdle!” And Steve bursts out laughing: “That’s not Bernie, that’s Ray Charles!”

And poor Ray Charles’ people were frantic looking for him. Then Bernie sauntered in, wearing distressed leather pants and purple hair.

When you watched the movie last night, did any specific memories come back to you?

Frantz: I remember that in “What a Day That Was,” I had a terrible cramp in my forearm, because it’s a high-tempo song and very repetitive. I thought, “Look at me, I’m smiling and I’m in agony.” [laughs]

Byrne: I remembered all the crew people, who I hadn’t seen in years.

Frantz: Our crew went on to high heights after that.

Weymouth: So did the band members. After our tour, there was a whole spate of bands saying, “I’m going to do that too!” And they got bigger bands. Us not being on tour left a big void that people could fill, like Depeche Mode and U2.

Harrison: Even the Rolling Stones.

Frantz: R.E.M., the Police.

Harrison: “Stop Making Sense” did start the possibility of having more people onstage and having more stuff to look at.

Frantz: After the final night of shooting, Peter Gabriel came backstage with Robbie Robertson. Peter had a little notebook and was making notes. Our show was a big influence on his own.

David, why was this the last Talking Heads tour?

Byrne: It was hard to think about how we could top this. That was the looming question. We didn’t have an immediate answer. Maybe in time we might have figured out a way to not get compared to this incredible thing we did, but immediately afterwards, it was like, oh man. Couldn’t think of anything.

Harrison: The next album was “Little Creatures,” which was us going back to a small ensemble. We had a thought of doing residencies in different cities with the four of us and maybe some of the others, but “Stop Making Sense” had an ongoing life of midnight shows, and the idea of competing with it was more difficult than it would have been for a film that had a run and ended.

Other than “Stop Making Sense,” what is the best music documentary?

Weymouth: [The Band’s] “The Last Waltz” or [Neil Young’s] “Rust Never Sleeps” maybe.

Harrison: “The Last Waltz” is a little too much of the Robbie Robertson story, and too little of the rest of the band. I did a film about Memphis music, “Take Me to the River,” which I think holds up really well.

Weymouth: “Spinal Tap!” After that, there was just no going back out there.

Frantz: I saw “Spinal Tap” for the first time during the “Stop Making Sense” tour, on the tour bus. The driver said, “What? You’ve never seen it?!” So we watched “Spinal Tap” and I thought, ohh, I can never take myself seriously again.

More to Read

The biggest entertainment stories

Get our big stories about Hollywood, film, television, music, arts, culture and more right in your inbox as soon as they publish.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.