The world often forgets: Elizabeth was the queen of music

- Share via

I heard the news when I clicked to the BBC Radio 3 website to catch the broadcast of the day’s Proms concert in London. I’m The Times’ classical music and dance critic, Mark Swed, filling in for columnist Carolina A. Miranda, and what I expected to hear was the Philadelphia Orchestra at Royal Albert Hall.

Elizabeth, queen of music

Following an announcement of Queen Elizabeth II’s death an hour earlier, Yannick Nézet-Séguin led the Philadelphians in “God Save the Queen” and “Nimrod” from Elgar’s “Enigma Variations.” The Thursday concert was canceled, as was Friday’s (which had been programmed to begin with Rachmaninoff’s spooky “Isle of the Dead”) and Saturday’s patriotic Last Night at the Proms free-for-all — all for the obvious reason.

The silencing of music was anything but characteristic of Elizabeth. Seventy years on the throne, 96 years on the planet, the queen generated far more classical music and engendered the art form more responsibly than any leader of modern times.

Her influence began in 1930 when Edward Elgar, appointed Master of the King’s Music, dedicated a delightful “Nursery Suite” to the 4-year-old Princess Elizabeth and her newborn sister, Princess Margaret. At 5, Elizabeth attended her first world premiere when Elgar conducted the concert premiere of the suite, which he already had recorded, making it the first orchestra score to receive its world premiere on a gramophone record.

The middle movement of seven is titled “The Sad Doll” and is unmistakably music by the composer of “Enigma.” With “Nimrod” as the first concert music played in memory of Elizabeth, a circle was completed. Not just a circle but an orb of exceptional size.

Elizabeth’s Buckingham Palace involved itself with artists and architects, poets and novelists, playwrights and actors, choreographers and dancers. Museums, galleries and theaters of all sorts received royal patronage. Movie stars, as well as celebrated pop and jazz musicians, mattered to the queen, and she to them. But classical music played a role in her historic reign unlike any other art.

Make the most of L.A.

Get our guide to events and happenings in the SoCal arts scene. In your inbox once a week.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.

To a considerable extent this was because music for ceremonial occasions has traditionally been classical. Beginning in 1626 when Charles I appointed a certain Nicholas Lanier as the first Master of the King’s Musick, there has always been a Master of the King’s (or Queen’s) Music. (The spelling changed during Elgar’s 1924-34 turn.) Every coronation needs a new coronation anthem. And much, much other ceremonial music. Vaughan Williams, Arthur Bliss and William Walton were the most famous composers to have written music for Elizabeth’s coronation in Westminster Abbey on June 2, 1953. But 25 composers from the 16th century to the modern era were represented. Handel — whose “Zadok the Priest,” which has been played at every coronation since that of King George II in 1727 — was the only non-Brit.

We would need volumes to chronicle all of the music made in Elizabeth’s name, all the composers and classical musicians she supported, all of those she invited to Buckingham Palace, all whom she made knights and dames, along with all the concerts and operas and ballets she attended around the world. Much of it, admittedly, has been music of the moment and forgotten. Walton’s “Orb and Sceptre” coronation march is an exception. Williams’ heavenly choral coronation miniature “O Taste and See” is well worth your two minutes. Arnold Bax’s “Morning Song (Maytime in Sussex),” written for Princess Elizabeth’s 21st birthday, in 1947, is all sunlight.

The biggest and most notable work for Elizabeth was Benjamin Britten’s opera “Gloriana,” a frank look at the relationship between Queen Elizabeth I and the Earl of Essex. Given its premiere by the Royal Opera six days after the coronation, it has long been held to be Britten’s one operatic failure. But that opinion has slowly been revised with revivals as well as performances of the terrific orchestral suite Britten made from it. Los Angeles Opera had hoped to mount “Gloriana” during the Britten centennial, but that fell through. It’s never too late, especially in this era of “The Crown.”

Elizabeth’s long reign encompassed four Masters of the Queen’s Music. They were Bliss, Malcolm Williamson, Peter Maxwell Davies (whose Ninth Symphony was written for Elizabeth) and Judith Weir. Weir’s “By Wisdom,” an anthem in tribute to Elizabeth, had its premiere at St. Paul’s Cathedral on June 3 as part of the Queen’s Platinum Jubilee.

For the record:

11:38 a.m. Sept. 16, 2022An earlier version of this article identified a dancer as Emily Johnson. The dancer is Sugar Vendil.

‘Being Future Being’

Last week in this newsletter, Carolina wrote about an exhibit by Wendy Red Star, who is of Apsáalooke heritage, restaging the Indian Congress of 1898 in Omaha at the Broad museum in downtown L.A. On Thursday in Santa Monica (with performances running through Saturday), it was the Broad Stage’s turn to acknowledge Indigenous art and the land that we inhabit with a staging of “Being Future Being.”

The work was created by Catalyst, the company of Emily Johnson, a choreographer of the Yup’ik Nation, who created the startling Native American dances for John Adams’ “Doctor Atomic” at Santa Fe Opera four years ago. “Being Future Being” employs an electronic score by Raven Chacon, this year’s Pulitzer Prize winner for music, which began outside the Santa Monica theater. We were asked to orient ourselves to land once home to Tatviam, Chumash and Tongva peoples. We stood apart and stomped. “When I jump on you,” Johnson said of the ground, ”you’re in me.”

Inside, the stage held a large mountain of dirt and some projections. A smaller mound was placed among the seats, as were platforms on which dancers could perform. When the ground is opening, there is no need for a fourth wall, and 20 audience members were invited to watch seated onstage as three ghostly figures, extravagantly dressed, quietly and mysteriously wandered around them.

The observer of “Being Future Being” is inevitably the outsider, which is to say that, at first exposure and without an insider’s grasp of its process and the spirit that spawns it, you should become whatever you make of it. Be they in quiet or frenzy, four dancers and Johnson seem possessed but also possess power. They do the stomp, releasing spirits, becoming spirits, speaking to us in a language we don’t understand and maybe they don’t either. Chacon’s tectonic score groans like the ground rumbling under our feet.

The artists involved are the future being, letting their identities flourish.

One exceptional dancer, Stacy Lynn Smith, describes herself as “a neurodivergent, mixed race/Black dance/performance artist with an extensive background in butoh, improvisational forms and experimental theater.” Others in the production bring vast ranges of other traditions and identities. The result is a mysterious whole. The future will be the future if we can welcome such inexplicable spirits without asking why.

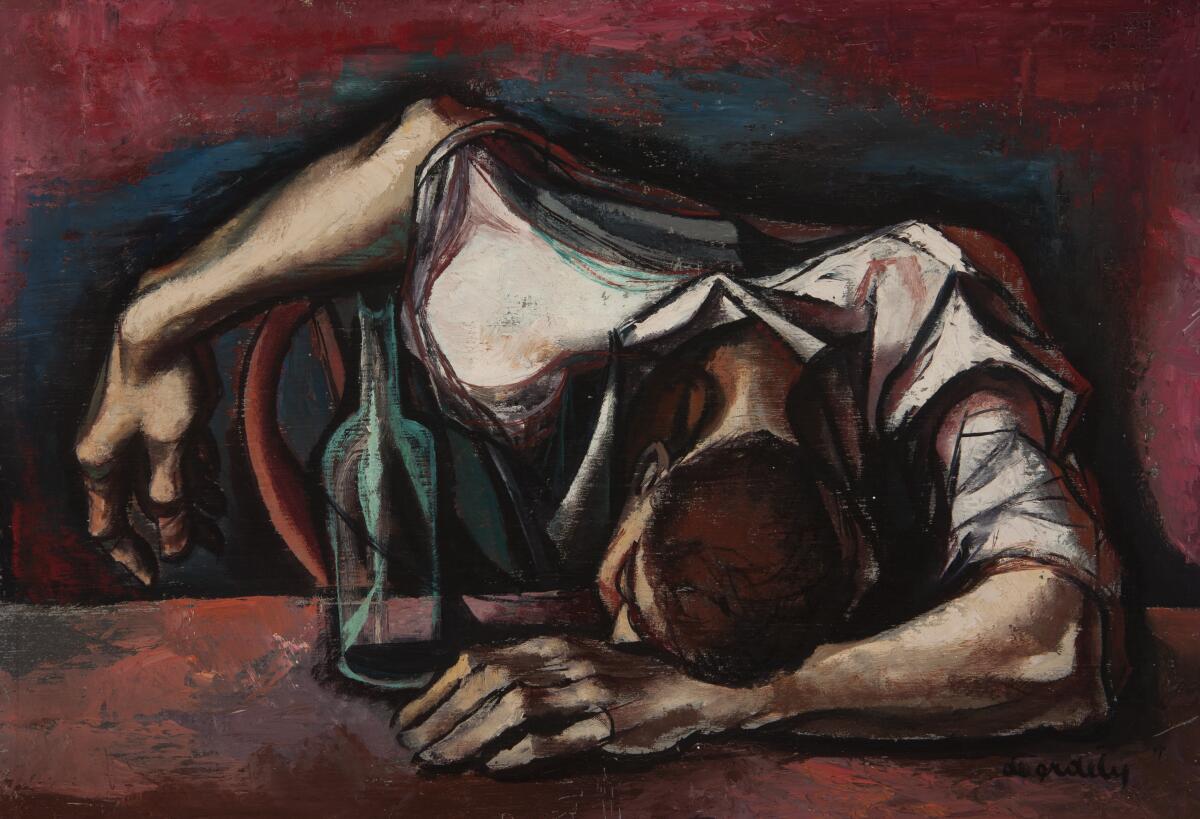

Visual arts

The list of the great European émigré artists who helped give Los Angeles its 20th century identity seldom includes Francis De Erdely. After seeing a small exhibition at the Laguna Art Museum, Times art critic Christopher Knight wonders whether the Hungarian painter — who fled the Gestapo, taught at USC and died in 1959 — has been unjustly forgotten. He was not, Knight reveals, the radical he is sometimes claimed to have been, and he didn’t exactly leave a legacy on the L.A. art scene. He was instead, Knight explains, “a conservative, if socially conscious, painter” who “occupies a modest historical nook.” But he was once prominent and, at his best, Knight concludes, worth knowing.

Enjoying this newsletter? Consider subscribing to the Los Angeles Times

Your support helps us deliver the news that matters most. Become a subscriber.

Classical notes

The first reviews of “Tár,” director Todd Field’s (“Little Children”) new film, starring Cate Blanchett as an ambitious rising-star conductor, have been glowing. “Her synapses fire like mad,” Times film critic Justin Chang writes about Blanchett’s performance after seeing the premiere at the Telluride Film Festival, “and her hands spring to inventive life as she describes her role in not just keeping but creating time.”

Lydia Tár may be a fictional conductor, but this film follows a slew of biopics about real conductors. Netflix is filming “Maestro,” in which Bradley Cooper stars as Leonard Bernstein. Israeli actor Shira Haas, star of “Unorthodox,” has signed on to play Ethel Stark, founder and conductor of the Montreal Women’s Symphony Orchestra in 1940, in “Ethel.” Then there will be Rupert Friend and John Malkovich portraying the mesmerizing Romanian conductor Sergiu Celibidache in various stages of his life in “The Yellow Tie,” to be directed by the conductor’s son, Serge Ioan Celebidachi.

In the it-just-so-happens department, Friend and Malkovich last appeared together in “The Libertine,” which had music written by the British minimalist Michael Nyman. And Nyman, whose career took off as a film and opera composer in the early movies by Peter Greenaway, is a topic in my interview with Greenaway about his use of music.

On and off the stage

The fall theater season is not quite upon us, but Broadway has already lighted up with Lea Michele’s debut as Fanny Brice in the “Funny Girl” revival. Times staff writer Nardine Saad addresses how the former “Glee” and “Spring Awakening” star has come to terms with accusations of bullying. At her first night in “Funny Girl” last week, the audience had its say about the production — with six standing ovations.

Moves

One of Queen Elizabeth’s last duties was to invite a newly elected Tory leader to become prime minister. And one of Liz Truss’ first appointments was Michelle Donelan as secretary of culture, who now has the responsibility to live up to Elizabeth’s arts legacy. Among Donelan’s previous jobs, the British art world is noting, was marketing manager of WWE.

New York Philharmonic music director Jaap van Zweden has announced that, once his tenure at Lincoln Center ends in 2024, he will become music director of the Seoul Philharmonic Orchestra.

Passages

Charlie Finch, the acerbic New York art critic, has died at 69 after falling from the window of his Manhattan apartment.

Lars Vogt, the eloquently understated German pianist and conductor who performed with inspirational grace throughout his cancer treatment, has died at 51.

Dianne Haigh, the architect who renovated London’s Southbank Centre, where Los Angeles Philharmonic conductor laureate Esa-Pekka Salonen held forth while music director of the Philharmonia Orchestra, has died at 73.

In other news

Plácido Domingo has apologized for what was reported to be so slapdash a performance in Italy’s Verona di Arena that the orchestra refused to stand for him.

Antiquities seized from the Metropolitan Art Museum have been returned to Italy.

Groundbreaking for Calder Gardens, by architects Herzog & de Meuron and landscape artist Piet Oudolf, will now be this fall. The planned center in downtown Philadelphia is dedicated to the art and ideas of native Philadelphian sculptor Alexander Calder.

And last but not least ...

King Charles III, who has long championed classical music, may have an impossible task of living up to his mother’s glorious record, but he did get off to a spectacular start. He was welcomed into the world in 1948 by Michael Tippett’s “Suite in D (for the Birthday of Prince Charles).” That, though, adds a further responsibility on the no-longer-future king to bring as much good cheer as Tippett’s irresistible suite does.

The biggest entertainment stories

Get our big stories about Hollywood, film, television, music, arts, culture and more right in your inbox as soon as they publish.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.