Commentary: With withering wit, The Times’ irrepressible Martin Bernheimer transformed criticism

- Share via

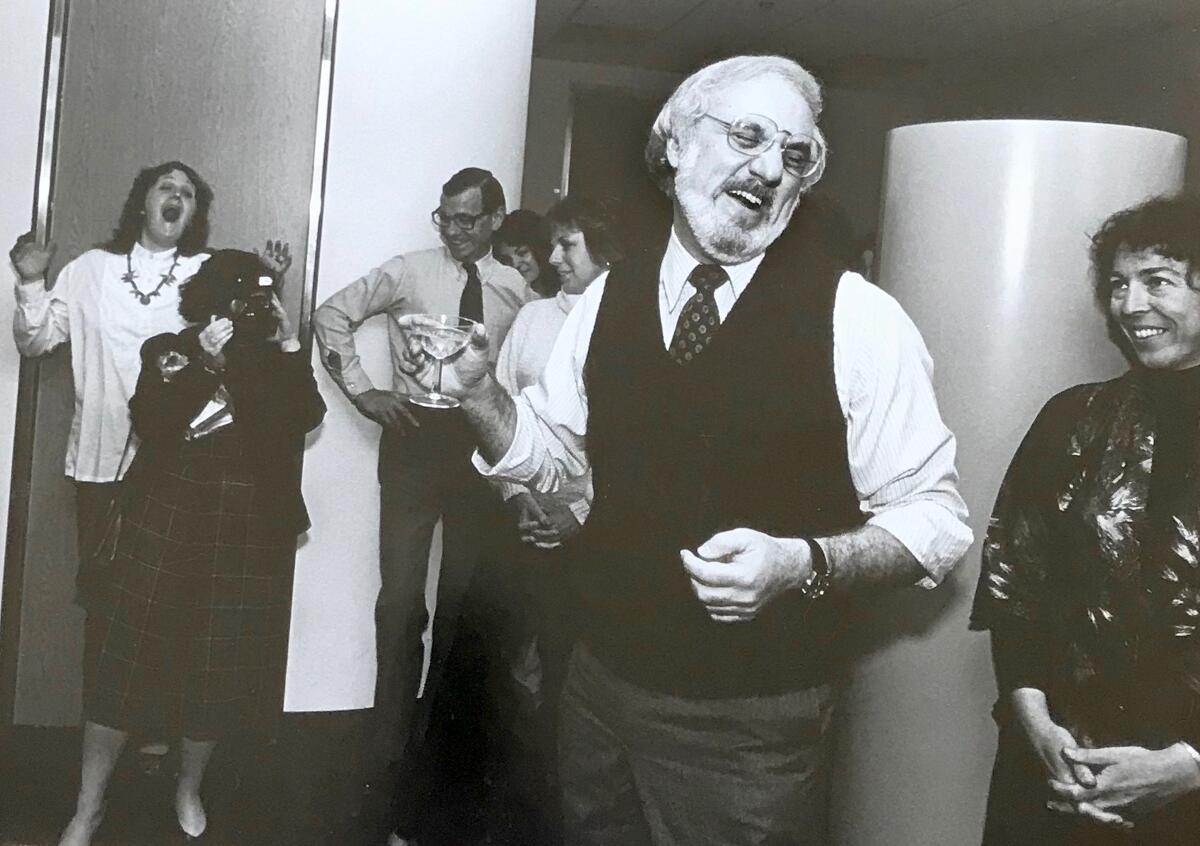

Martin Bernheimer, music critic for the Los Angeles Times from 1965 to 1996, was a Pulitzer Prize winner who attacked philistinism without fear wherever he saw it. He heralded the virtuous. He was outrageous. He was loathed, and he was loved. He was very funny. He had an immediately recognizable style. He covered up, beneath layers of ferocity, what was said to be (and was now and then exhibited as) a heart of gold.

Most of all, he was read. He was talked about and still is by older-timers in, to use a Bernheimerism, the land of the plastic lotus. He was a criticism legend in his time. His death Sunday in New York shortly after his 83rd birthday is the end of an era. Repeat, end of an era. That last sentence is another Bernheimerism.

He made enemies. Mstislav Rostropovich, the legendary Russian cellist, once said he would never return to Los Angeles after being belittled for the last time in a Bernheimer review. Bernheimer led an epic battle with Ernest Fleischmann, the imperious, visionary executive director of the Los Angeles Philharmonic. Bernheimer so infuriated Fleischmann’s predecessor at the L.A. Phil, Dorothy Buffum Chandler, that she had him fired on occasion, only for her son, Times publisher Otis Chandler, to rebelliously rehire Bernheimer the next day.

“Never overestimate the power of a superstar,” Bernheimer began a 1983 review of Leonard Bernstein conducting a student orchestra at the Hollywood Bowl, pointing out that the “media darling” couldn’t draw much of a crowd, only 5,062. He then noted that the “crowd that did show up Sunday proved more notable for enthusiasm than for sophistication.” He went on to say that there wasn’t “much to stomp and whoop about in the Brahms,” a performance of the Fourth Symphony.

“Inspiration seemed in short supply,” Bernheimer added, “still one was grateful that the conductor spared us romantic excess along with most of his usual podium gymnastics.” Bernheimer knew of which he wrote, sparing the reader some of his own literary gymnastics.

The summer before, Bernheimer had described “Lennie Bernstein” as “a great American showman. He dances. He flirts with the piano. He talks. He sells. He ennobles trivia. He even writes high-class, superclever, sentimental, sophisticated Popmusik.”

The morning the Brahms review ran, Bernstein had a rehearsal with the L.A. Phil that I happened to attend. The great American showman was in a foul mood and at one point blew up at an unresponsive orchestra, asking, “What’s the matter? Do you have Bernheimer’s disease?” as he stormed off to his dressing room. Bernstein also penned a letter to the editor that was a brilliantly biting parody of Bernheimer’s writing style.

Those were the days. They don’t make them like Bernheimer anymore.

Spanish conductor Jaime Martín wows in his first concert as music director of the Los Angeles Chamber Orchestra, premiering Andrew Norman’s “Begin.”

I was never, as much of the classical critical profession is today, a Bernheimer-ite. I, of course, knew him. We talked — chatted is more like it — at concerts. Only once, very early in my career, did I have a meal with him, when he invited me to lunch at The Times, wondering whether I might want to freelance for him. He needed someone to write about new music, a subject that didn’t interest him much. He also told me that I had no real future in criticism. I wasn’t tough enough.

I was disappointed that he didn’t show me his office, where he had an infamous collage of nude and semi-nude female performers. It was a different time, but even so he got away with murder.

And yet, Martin Bernheimer has loomed over my career from the start. I would never have become a critic had it not been for Martin. A friend who had taken Bernheimer’s course in criticism at UCLA suggested that since I hated music critics so much, I should try my hand at the work, and he recommended me to one of his friends from Bernheimer’s class, Donna Perlmutter, who had become chief critic of L.A.’s then-second paper, the Herald Examiner. My training had been in musicology and theory. I learned about criticism firsthand, and secondhand, through Martin, and through him caught the newspaper bug.

When I eventually succeeded Perlmutter at the Herald, I was daunted to be competing with Martin, the most brilliant stylist in the business, and one who knew his stuff so well that his seeming glibness had a deadly sting. When I finally succeeded Martin at The Times, I was up against Martin’s legacy. My goal may have been, partly, to undo some of the damage I perceived he had done to the L.A. arts scene. But the tools I had came directly from what I had learned from him.

They say it is difficult to follow a huge presence. The fact is that it also can be great. Martin demanded to be treated with regard, for himself but also for his position and for everyone else at The Times. He had so put the fear of God in everyone that publicists and institutions kowtowed to me, making sure I was happy with my parking, my seat, that I had everything I needed. That changed soon enough, once it became clear that I felt all of this to be excessive. But it was fun to be treated like a big shot while it lasted.

At first I was the Un-Bernheimer, championing what Martin disapproved of. That Bernstein Brahms Fourth, for instance, was to me the most sensuous performance of the symphony I had ever heard, and I’ve not encountered its like since. In his battles with Fleischmann, Martin had not been particularly supportive of the building of Walt Disney Concert Hall or the direction of the L.A. Phil under Esa-Pekka Salonen, both of which I saw as crucial to the future of L.A.

My model as an activist critic was not Martin but John Rockwell at the New York Times. Through his enthusiasm and insight, he played a critical role in creating the SoHo music scene and the budding of Minimalism, as well as the rethinking of modern music, both classical and pop, for the world as it was, not as it was imagined from an elite perch. But Martin had a hand in even that. Rockwell got his first big break when Bernheimer hired him at The Times, which is how the New York Times got wind of him.

Martin demanded the maintenance of standards he felt essential, and he had no mercy for those who didn’t live up to his high ideals. He is remembered for harping on Zubin Mehta’s flashiness, which is what got him in trouble with Mrs. Chandler, who had hired Mehta at the L.A. Phil.

Hearing of Martin’s death Sunday, I spent a couple of hours going through The Times’ archives, reading him with delight and dismay, which I expected, but also with surprise at his fairness. I remembered the zingers but found them less prominent than I’d expected as I randomly picked through his thousands of pieces. He almost never attacked without also giving credit, which, of course, made the attacks all the more pointed.

With Plácido Domingo absent for the season opener, L.A. Opera kicks off a Barrie Kosky take on Puccini that’s pointed toward a new generation.

On the average, I found far more positive evaluations of Mehta than put-downs. It was Bernheimer’s regard for Mehta’s skills as a conductor and for his championing of less traveled parts of the repertory, especially the music of Schoenberg, that made Martin decry what he felt were Mehta’s sometime lapses in taste and good musical manners.

In 1970, describing Mehta having “triumphantly returned to his home podium” after a short absence, Martin compared the L.A. Phil to “the proverbial girl with the curl. When it is good, it is very good indeed, and when it is bad, it is sloppy.

“It was very good indeed Thursday night.”

The problem is that when he wrote well, you remembered his waggishness. Here the start of another review I came across looking for what it was that so upset Rostropovich.

“Pauley want a concert?

“Nobody plays basketball at the Dorothy Chandler Pavilion of the Music Center. Why, one might wonder, must Mstislav Rostropovich and the National Symphony play music at the Pauley Pavilion of UCLA?”

Skipping to the end: “After intermission — what, no popcorn, no hot dogs? — [Rostropovich] embarked on a characteristically soulful traversal of the Tchaikovsky Fifth Symphony, which Los Angeles hadn’t heard since the Philharmonic played it last week. (Doesn’t any left hand around here know, or care, what the right hand is doing?)”

Martin was king of the kicker, the last lines of a review. He larded his coverage of a preview concert performance of John Adams’ “Nixon in China” with such sarcastic descriptions of the score as “amusing movie-music bilge for satirical effect” and “doodledy-doodledy instrumental meanderings,” saying it treaded “a precarious line between caricature and pathos” that ultimately “falters. And falters. And falters.”

The preview featured the cast that would appear in the staged premiere with the exception of one character in the opera. Martin’s contemptuous kicker: “Under the circumstances, one left this complex and lofty endeavor haunted by only one profound question.

“One wondered who’s Kissinger now.”

Only Martin could do that. But to his credit, three years later when “Nixon” was performed by the Music Center Opera (now Los Angeles Opera), he wrote, “Even critical ogres can undergo a change of mind.”

I observed a sigh of relief when I arrived at The Times. Martin had begun detecting Philistines everywhere. He had become bitter and difficult to work with. But for three decades, he had a profound effect on L.A. He challenged us to be big-time. Opera was his greatest passion, and he fought for it. He was also dance critic and fought for dance, too. L.A. was way behind in both, and the attention he gave was meaningful.

It doesn’t matter how you feel about Martin. When you read him, you realize just how stupid you look if you don’t understand the necessity for critical thinking in all aspects of life.

Martin never wanted to write a book. He never collected his criticism. He considered himself a journalist who wrote for the moment, not posterity. He believed fervently in the essential need for informed, yet entertaining, daily dialogue. No wonder he became a little bitter in the end.

This fall’s classical music highlights include Esa-Pekka Salonen, “Porgy and Bess” and the L.A. Phil’s birthday gala.

More to Read

The biggest entertainment stories

Get our big stories about Hollywood, film, television, music, arts, culture and more right in your inbox as soon as they publish.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.