Review: Shirin Neshat show at the Broad wrings power, pain and poetry from black-and-white

- Share via

Given an image-world long awash in color photographs, films and videos, black-and-white pictures play a surprising role in the work of artist Shirin Neshat.

Among the more than 230 photographs in her retrospective exhibition at the Broad, color rarely shows up. When it does make an appearance, including in some of her eight projected-video installations, color more often than not plays in a minor key. Neshat’s choice of a neutral, mostly black-and-white palette is unusual but it operates in a subtly powerful way.

Black-and-white used to be a given for mass-culture imagery. That began to change after World War II, first slowly and then with increasing speed.

By the end of the 1950s, color became common for movies. In 1965, television underwent a color revolution. By the end of the 1970s, newspapers were using color photographs with regularity — a shift that was not without controversy, since black-and-white was thought to have an intrinsic gravity that matched the black ink of the printed journalistic word.

By the time Neshat picked up a camera in 1990 and began to work as an artist, the changeover to color was long since complete. Mass-culture imagery was now presented almost exclusively in colorful hues, as it has been ever since.

That matters for one important reason: Neshat is Iranian, her work exclusively focused on the conditions of a culture from which she has lived in exile for decades. The image of Iran that an American carries in his mind is almost exclusively crafted by mass-culture pictures. Neshat’s say: Reconsider.

Born in Iran in 1957, the artist went to school in California at 17 and has lived in New York since 1983. In the long aftermath of the popular uprising of the Islamic Revolution against the monarchy in 1978-79, black-and-white pictures stand in stark contrast to the flood of images on TV and in papers witnessed in the West. Aesthetically they possess an old-fashioned, even archaic aura — history framed with the respect afforded to photographs as capital-A art.

“Black and white are the colors of photography,” the celebrated Swiss American documentary photography Robert Frank once insisted.

Yet the imagery that Neshat constructs in those “colors of photography” can be destabilizing. Her photographs, mostly portraits, are formal, sober and considered, contrary to the topical flow of most photojournalism.

Her videos construct narratives with an almost ceremonial edge. Neshat’s art makes a point of distinguishing itself from the clichés and assumptions of popular culture. The absence of color is an inconspicuous but effective way to italicize the difference.

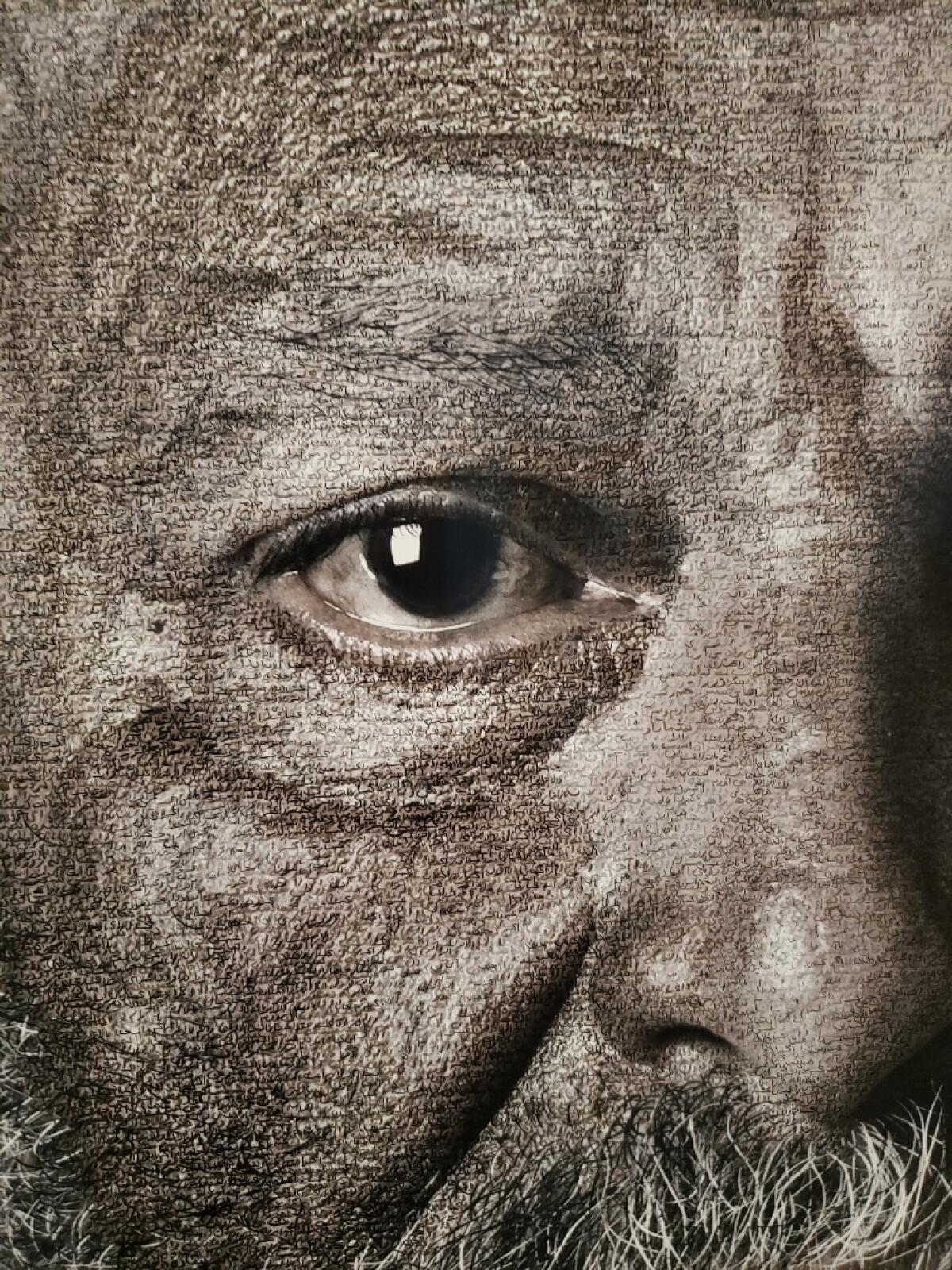

“Women of Allah,” a series begun in 1993 and her first significant body of work, opens the exhibition. Most of the dozen or so pictures are self-portraits. In several, Neshat shows herself in traditional dress, her exposed skin covered in delicate Farsi and Arabic writing. She is posed with a rifle or handgun.

The rifle is held upright before her, stands by her side, aims straight at the viewer or pokes out from the Muslim veil by her face. The barrel is clasped between her feet, their soles covered in dramatic calligraphy. A handgun is held up, conspicuously layered over her mouth.

The camera shoots, but the artist is prepared to shoot back.

Neshat has credited the manifold self-portrait paintings of Mexican artist Frida Kahlo as one inspiration for “Women of Allah.” Kahlo’s obsessive interest in inserting herself into established visual culture was itself inspired by the Mexican Revolution, her paintings’ iconic personal format derived from the male hero-worship so prevalent in the era’s Communist propaganda. (Think of the imposing, ubiquitous portrait heads of Lenin, Stalin and Mao.) Like those paintings, Neshat’s photographs also suggest pain transformed into art, but without Kahlo’s self-mythologizing cult of personality.

The series, made in three sets over four years, includes a nearly life-size photograph of a Muslim woman fully veiled in black, head to toe. One arm is exposed, emerging from the shroud-like garment to hold the hand of a naked little boy. Neshat has drawn on the photograph with black ink, decorating the boy’s skin with heraldic, floral, paisley and other traditional patterns.

Mother and child both wear veils — hers literal, his metaphorical. In his nakedness he is publicly displayed, clothed only in his culture’s artistic signs of communal ritual and social custom. She is likewise formally swathed, but her civilizing robe conceals her. His veil exposes him, hers keeps her hidden.

Neshat often writes on her photographs, usually in tiny script. (She was born in Qazvin, once the Persian capital of the Safavid Dynasty and a celebrated center for the important art of calligraphy.) Almost all her photographs are portraits, and the writing technique establishes a subtle tension: The looming faces push a viewer back, the minuscule lettering pulls you in close.

Unless Farsi and Arabic are languages known to an audience, the writing functions as a tool for psychological distance: Physical intimacy with a stranger’s face is no guarantee of understanding, save for the power of human identification. For those who do read those languages, however, I imagine the quoted poetry — most of it by women, some of it feminist — adds a distinctive connection.

Broad curator Ed Schad, who ably organized the exhibition, has alternated rooms of photographs with eight projected-video installations. (Some of the videos have been transferred from films.) The only misstep is “Illusions and Mirrors,” a relatively recent single-channel narrative made in 2013.

It follows a lovely, mysterious young woman through the shabby, empty rooms of a ruined mansion and across the barely populated sands of a windswept beach, to no particular effect. The romanticized journey through time and space, past and present, culture and nature isn’t helped by the immediate recognition of the actress as Natalie Portman, a celebrity identification that snaps a viewer out of any poetic reflection. The interruption is jarring.

Like the still photographs, the best installations create compositions that make the relationship between picture and viewer dynamic rather than static. “Turbulent,” the earliest (1998), is emblematic. Screens are mounted on opposite walls, requiring a viewer to ping-pong back and forth, interrupting passive consumption.

On one side, a man on a theater stage sings soulfully before an all-male audience; they are spellbound by his exceptional performance. On the other, a woman seen from behind sings before an empty theater, the lyrical sound of her voice compelling awe.

The camera on him is mostly static, while on her it begins to circle the singer — until suddenly we realize that an audience is indeed present. We are the audience seated before her, hearing her song. That simple recognition ignites an unexpected feeling of privilege to be watching, listening — especially as restrictions have been placed on women singing in public since the 1979 Iranian Revolution.

The gender differences are received differently. He gains our earnest admiration for his exceptional gift, while she sparks a deeply emotional connection with hers.

The videos represent Neshat’s primary achievement, especially in earlier examples “Rapture,” “Passage” and “Tooba,” in addition to “Turbulent.” Time-based, the installations alone require more than 1½ hours to see in their entirety. Plan accordingly when you go to see the show.

Shirin Neshat 'I Will Greet the Sun Again'

Where: Broad Museum, 221 S. Grand Ave., L.A.

When: Tuesdays-Sundays, through Feb. 16

Admission: $12-$20 (special exhibition)

Info: (213) 232-6200, www.thebroad.org

More to Read

The biggest entertainment stories

Get our big stories about Hollywood, film, television, music, arts, culture and more right in your inbox as soon as they publish.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.