Black Hollywood is rising up to support Black Lives Matter. Here’s how

- Share via

Tessa Thompson shouted for Los Angeles Mayor Eric Garcetti to defund the police in front of the Getty House, the official mayoral residence. “605 South Irving,” an organizer yelled. “Tell people to pull up.”

“Care, not cops!” the crowd clamored. “Where you at, Eric?” they asked.

Thompson turned out to a Pan Pacific Park protest with her family. The demonstration escalated into violence, she said — but only after police appeared.

She met with her community in a church on her family’s doorstep in West Adams to discuss defunding the police. When she attended a demonstration of more than 50,000 people near where she grew up, she said, it felt “full circle.”

Black Hollywood artists like Thompson (“Westworld”) have been increasingly active in supporting Black Lives Matter across Los Angeles. Michael B. Jordan — whose 2019 film “Just Mercy” highlights deep systemic inequalities in criminal justice — marched in solidarity with BLM and called on Hollywood to invest in Black storytelling. Keke Palmer (“Hustlers”) went viral after challenging the National Guard to march with protesters in Hollywood. “Watchmen” star Regina King — like Thompson an L.A. native — opened up to Jimmy Kimmel on his talk show about the necessity of ongoing protests.

“At all of those protests that I’ve been to, all of those demonstrations, I’ve seen entertainers in the industry there as well,” Thompson told The Times. “It seems that there’s sometimes this perception when people that have a public platform are talking about these issues as people, they’re somehow separate. And I think it’s really important to remember that all of these folks are people that come from neighborhoods.”

Los Angeles and its neighborhoods formed the cradle of Black Lives Matter. It was here on July 13, 2013 — the day George Zimmerman was acquitted in the murder of Trayvon Martin — that the movement’s first chapter was born.

The city is also the home of the entertainment industry, which holds a unique power to shape the understanding of Black lives in America and around the world. Only here could Black Hollywood artists protest, organize and engage alongside Black Lives Matter cofounder Patrisse Cullors and Black Lives Matter L.A. leader Melina Abdullah.

“I think the more creatives that speak out about the role of Hollywood in both perpetuating but also ending systems of overpolicing, the better,” Abdullah said. “Not just do it now, because we’re kind of hot right now. But we want them to be in the work for the long haul.”

The Times interviewed nearly two dozen Black entertainment industry voices, spanning directors, producers, writers, designers, agents and executives. They discussed racism in Hollywood, what needs to change and their frustration with years of talk and little action by powerful companies.

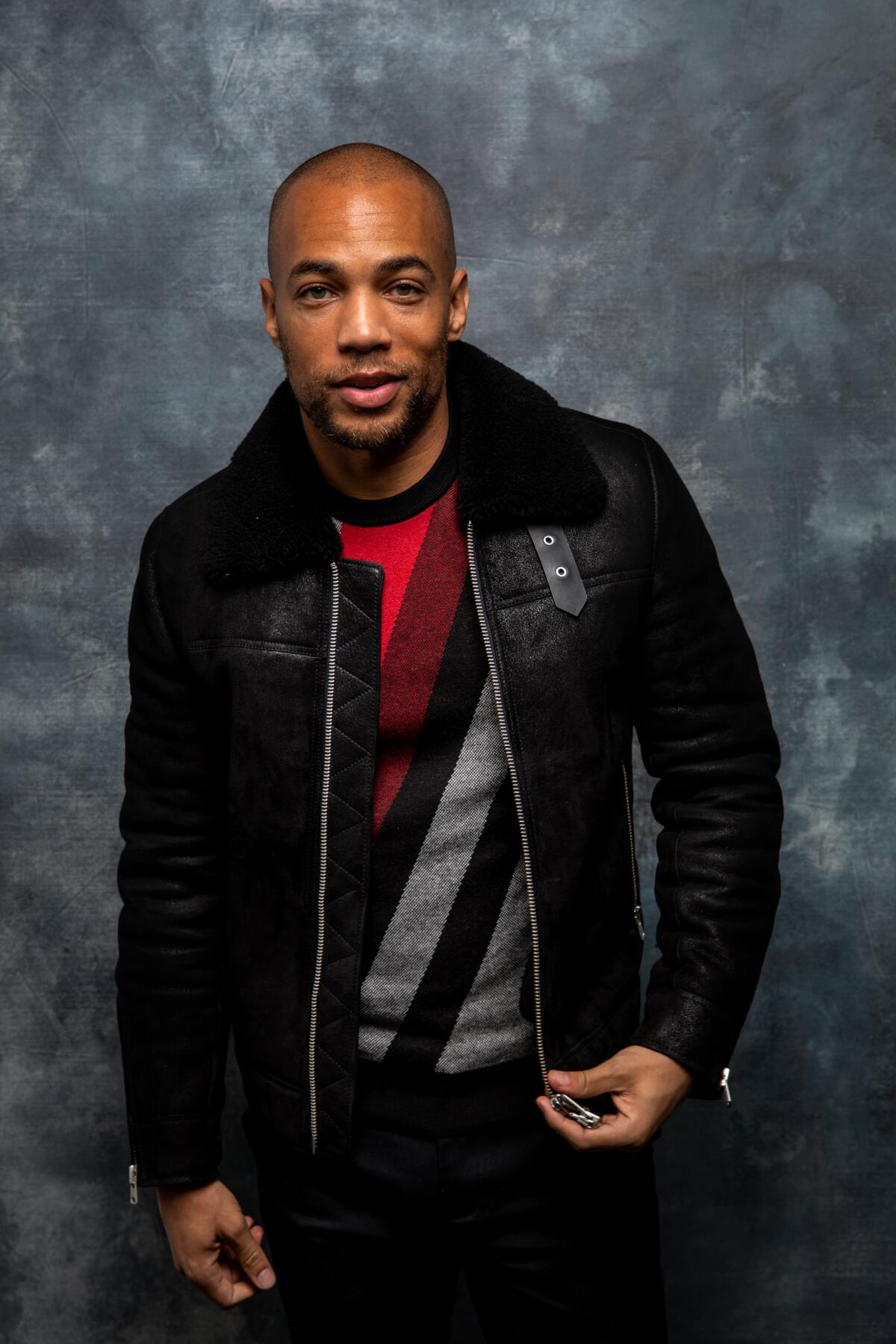

Abdullah and Cullors recently worked alongside Thompson and actor Kendrick Sampson (“Insecure,” “Miss Juneteenth”) on the “Hollywood 4 Black Lives” open letter published by BLD PWR, Sampson’s activist organization, which has been organizing alongside BLM for at least five years.

“We’ve had a very deep and longstanding relationship with Kendrick, and what we’ve seen with him in his work is the power that Hollywood has when they get behind a movement,” Abdullah said. “The way in which Kendrick has been involved in Black Lives Matter has been really principled — so not trying to change or water down our messaging, just trying to figure out how he could be useful.”

“We are in a moment where, as Dr. Melina Abdullah would say, the world has cracked wide open,” said Sampson, who has shown up for countless protests. “People are ready for a paradigm shift. They’re ready for real change.”

BLD PWR’s letter to Hollywood leans full force into that shift, calling on the industry to divest from police and anti-Black content and invest in anti-racist content, Black careers and the Black community. Sampson believes in uprooting systems of injustice.

“I say it all the time, it’s my favorite church saying: The bad seeds produce the bad tree produces bad fruit,” he said. “You have to uproot those systems and plant new seeds.”

While the entertainment community seems to have gotten on board with an emphasis on diversity and inclusion in front of the camera, activists like Sampson are also championing inclusivity behind the scenes.

“We have to imagine — and we have more than enough imagination in Hollywood — imagine new ways to operate, where it is more equitable, where it does achieve liberation, and allow Black creatives and Black execs and Black below-the-line folks to thrive,” Sampson said. “Because there’s enough resources for everyone.”

Zuri Adele, who has demonstrated side by side with Sampson, Cullors and Abdullah, stars in “Good Trouble,” a spinoff of the Freeform TV show “The Fosters,” as activist Malika Williams. She also highlights extending inclusivity off-camera.

“Those decisions need to be made about even, like, how are those people’s hair being done?” she said. “Are they having a micro-aggressive experience in the hair and makeup trailer? Are we having a Black person who knows how to? Or how are they being lit? … Does the crew reflect the world? Or the world we want to see?”

Joanna Johnson, co-creator and showrunner of “Good Trouble,” began work on Adele’s character in wake of Stephon Clark’s killing by Sacramento police. When Johnson brought Cullors on as a consultant to the BLM storyline in 2018, the movement was just beginning to gain popular support.

Cullors and Abdullah play themselves on the show; they are role models for Malika as she leads protests in response to a police shooting of a young Black man.

This plotline marks a stark shift from the narratives that dominate such popular shows as “Law & Order: SVU” and “Brooklyn Nine-Nine,” which largely center cops as heroes. The nonprofit advocacy group Color of Change found in a January report that the scripted crime genre popularizes distorted representations of justice, race and gender.

From ‘Law & Order’ to ‘Cops,’ we’re at a moment of reckoning for the depiction of police on TV. But change will require us to stop lionizing rogues and scamps.

“What we have generally when we think about Hollywood is the telling of stories from a white supremacist perspective — so from the perspective of white people,” Abdullah said. “You also have the telling of stories in ways that amplify or… try to present it from the perspective of the current police state, which we see as hugely problematic.”

“Good Trouble,” on the other hand, centers Black radical organizing and the fight for Black freedom. After joining the show as a consultant, Cullors has since entered the writers room for Season 2.

“Across the way, that’s how Hollywood can support Black Lives Matter: by representation and hiring and sharing power and making room at the table — and sometimes giving up your seat at the table so that people are represented,” said Johnson, who is white.

“I think allyship is to make space and then to allow Black leadership to guide you and not trying to be the leader.”

Adele has shadowed Cullors, her on-screen inspiration, at BLM L.A. and Reform L.A. Jails meetings, which bled into attending protests with her as well. The actress’ first time protesting with the movement came after “Good Trouble.”

“When we film the protests and when we do it in real life… we’re chanting, we’re doing all the same things, we’re calling the names of people who are now our ancestors,” Adele said. “It’s a beautiful ritual that I’m glad to do at work and in life. I feel like my purpose is so much bigger than I knew.”

Like Adele, Black stars from across Hollywood have demonstrated alongside Cullors and Abdullah, most prominently at BLM L.A.’s regular Wednesday “Jackie Lacey Must Go” protests in opposition to the district attorney’s record of failing to prosecute killings by police. Thompson and Sampson have attended, as have Anthony Anderson (“Black-ish”), Meagan Good (“Think Like a Man,” “Minority Report”) and Cedric the Entertainer (“Be Cool,” “Barbershop”).

For Good, whose father was a member of the LAPD for more than 20 years, the Lacey protests offer a specific, intentional way to get involved after the death of George Floyd.

“The week that George Floyd passed away, I was really struggling,” Good said. “I got really, really depressed, and I got really overwhelmed. And I was praying about it. I was like, ‘How do I get through this?’ Because I really was feeling hopeless.”

That sense of hopelessness — as well as her experiences with racism growing up and a desire to learn about Black history — motivated her to seek out ways to make change. The June 10 Lacey demonstration wasn’t her first protest, but it was her first experience with #JackieLaceyMustGo, and she’s attended a few of the rallies since.

At that protest, Good was asked to speak. Her first impulse was to say no, but when she felt a “tugging in her spirit,” she decided to step up. She spoke about how the COVID-19 crisis has allowed for a greater focus on the movement, and her belief that this was “100% a God thing.”

Good’s activism is informed by her faith; her husband, DeVon Franklin, is a preacher and film producer who in May 2019 joined the board of the Academy of Motion Picture Arts and Sciences as a governor-at-large. The move was part of the academy’s A2020 initiative, which aims to increase representation and support inclusion within the film community.

“That ain’t enough for me,” actress Keke Palmer said when National Guardsmen took a knee after she urged them to march alongside protesters in Hollywood.

Good underscores Hollywood’s responsibility for the portrayal of Black experience. “That direct reflection does perpetuate racism or not,” she said. “It does tell you that we are not gangsters and we’re not just here to shuck and jive and make you laugh. We are real human beings with real human stories that can be anybody’s color and anybody’s nationality.”

The actress was one of the more than 100 Black celebrities — from Jesse Williams to T.I. — who attended Cedric the Entertainer’s “Hollywood 100” event at his home in 2016. It was there that Cedric and Good “really got locked into” BLM and BLD PWR, Cedric said.

Cedric echoes a sentiment that most of the entertainment activists who spoke to The Times share: When they first got involved, BLM was perceived as radical or even dangerous. Today, public sentiment has begun to swing in favor of the movement.

“George Floyd’s murder… was one that provoked so many of us, which led to the mass group of multicultural protests that you see right now,” Cedric added. “And that, of course, includes Hollywood. So you’re definitely starting to see more people become involved, become more concerned, wanting to lend their voices more.”

The comedian joined the movement shortly after the 2014 police shooting of Michael Brown in Ferguson, Mo. Cedric is a firm believer in lending his personality and platform to elevate both BLM and BLD PWR. He hails organizers like Abdullah and artists like Sampson for continuing to push for change, “whether there’s cameras or not.”

“Regardless if people are looking, regardless if it’s a big flashpoint or anything, they’re there,” Cedric said. “So I just wanted to show support for that and really encourage other people to understand who these people were that they were listening to and what their fight was about.”

More to Read

The biggest entertainment stories

Get our big stories about Hollywood, film, television, music, arts, culture and more right in your inbox as soon as they publish.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.