Best classical music of 2020: 10 heroes who came to our rescue in a horrendous year

- Share via

Twenty-twenty was the year that was, however much for classical music it may have seemed the year that wasn’t. Live performance, as we knew it, came to a sudden halt early March.

In startling advance of the Black Lives Matter protests, the Los Angeles Philharmonic happened to be in the middle of its revolutionary Power to the People! festival, examining the artistic legacy of Black protest movements and the issues of racial and economic inequality. Well before the presidential election, Yuval Sharon’s innovative opera company, the Industry, had to cut short its run of “Sweet Land,” an acute questioning of America’s foundation myths, exposing our democracy’s fragility. With summer wildfires still in the future but the pandemic at our doorstep, UCLA‘s Center for the Art of Performance barely squeaked in its operatic treatment of Octavia Butler’s prophetic novel “Parable of the Sower,” forecasting the dire social and political consequences of environmental irresponsibility.

Movie theaters closed. Broadway went dark. Concert venues fell silent.

Admirable local institutions of all sizes — Los Angles Opera, Los Angeles Master Chorale, Los Angeles Chamber Orchestra, Piano Spheres, Boston Court, New West Symphony, the Wallis and REDCAT among them — rose to find innovative ways to keep the music coming online and to continue the discussion of potent issues.

But let this year’s top 10 go to classical music first responders who magnificently kept music mattering.

Gustavo Dudamel. The L.A. Phil’s music and artistic director began the year with an extraordinary cycle of Charles Ives’ four symphonies, performances arresting in their multifaceted approach to Americana. Now released as downloads, they have been nominated for (and damned well better win) two Grammys. With the first months of pandemic spring spent brainstorming with L.A. Phil management about how to contend with a projected $100 million loss of income from Hollywood Bowl and Walt Disney Concert Hall performances, Dudamel emerged in a radio series from his home, a themed television series of Hollywood Bowl highlights and an online series of new concerts with the conductor and orchestra filmed over the summer in a cavernously empty Bowl. Off in Europe, where concerts have proved more feasible and where many are livestreamed, Dudamel led a ravishing “Firebird” with the Vienna Philharmonic at the Salzburg Festival. A Schumann cycle in Munich with the Bavarian Radio Orchestra was so exciting, that great orchestra, shopping for a music director, may well be dangling an offer. Dudamel couldn’t be missed this fall in Spain, where he starred in an immersive virtual reality film, “Symphony,” that toured the country and conducted his first “Il Trovatore” in Barcelona.

Esa-Pekka Salonen. Besides conducting orchestras (with and without audiences) in London, Helsinki, Paris, Hamburg and San Francisco, the L.A. Phil’s visionary laureate conductor found that the break in his schedule allowed him to pursue his love of technology. At Finnish National Opera, he helped to create an artificial intelligence singer, Laila. He began his tenure at the San Francisco Symphony with an AI-friendly digital concert, and he led his old London orchestra, the Philharmonia, in an extraordinary digital realization of Beethoven’s little-heard ballet, “Prometheus.” But what he will be most remembered for during the pandemic is the riotous “Covid fan Tutte” he conducted at Finnish National Opera and the broadcast with the Philharmonia of a haunting performance of Britten’s “Les Illuminations” with Julia Bullock that perfectly captured the surreal emotions so common to our present state.

Mirga Grazinyte-Tyla. The L.A. Phil’s phenomenal former associate conductor, now a bona fide star music director of the City of Birmingham Symphony Orchestra, had an especially eventful year. She came down with COVID-19 in March. By the beginning of June, visibly pregnant, she jumped in to conduct the Berlin Concert Hall Orchestra in a livestreamed concert in Dortmund, Germany, that ended with a skin-tinglingly expressive Beethoven Fourth that felt all about future promise. After taking the summer off for the birth of her second boy, Mirga was back in Birmingham, England, celebrating the orchestra’s 100th birthday. Like Salonen, she made a major Britten statement, recording the composer’s wartime “Sinfonia da Requiem,” a riveting statement of loss and wonder ripe for a pandemic year. Get it!

Yuval Sharon. “Sweet Land,” more than any other Industry project, redefined opera with its imaginative use of a downtown park and the vast yet refined scope of music by Chinese émigré composer Du Yun and Native American Raven Chacon, as well as pairs of librettists and directors. In Detroit, where Sharon was named artistic director of Michigan Opera Theater, he staged a pandemic-centric version of Wagner’s “Götterdämmerung” in a parking garage. One good thing to come out of America’s disastrous coronavirus year is that this minor U.S. company is poised to become one of its most important. Meanwhile, as interim artistic advisor of Long Beach Opera, Sharon has come up with a seemingly feasible and unmissable season next year of operatic revitalization.

Patricia Kopatchinskaja. The irrepressible violinist, one of the world’s great instrumental virtuosos, also proved a virtuoso of moods, from exhilaration to doom. As she does every year, she lived onstage as if were her, and the Earth’s, last. She gave recitals in what was left of Europe’s summer festivals, many of them broadcast, treating Beethoven, Ravel and Schubert with life-and-death urgency. In a German orchestra concert steamed live from Stuttgart, she sat on the floor facing the conductor, Teodor Currentzis, also on the floor, playing the bizarre Baroque music. Her new recording “What Next Vivaldi?” is not only the most astonishing Vivaldi playing on record but also the craziest, as musically mixed up as our emotional lives have become. Get it!

Deborah Borda. Even without the pandemic the L.A. Phil’s transformative former president and CEO would have had her hands full turning around the formerly dysfunctional New York Philharmonic. Yet, despite the horror of New York City’s deadly COVID surge and Dutch music director Jaap van Zweden getting stuck in Amsterdam, she stayed in constant, honest touch with her audience, oversaw what may have been the best pandemic orchestra website, put her players on the backs of flatbed trucks throughout the boroughs when that was safe, and somehow managed to salvage, in the midst of a budgetary catastrophe, a feasible renovation of David Geffen Hall, something no one else has been able to do for decades.

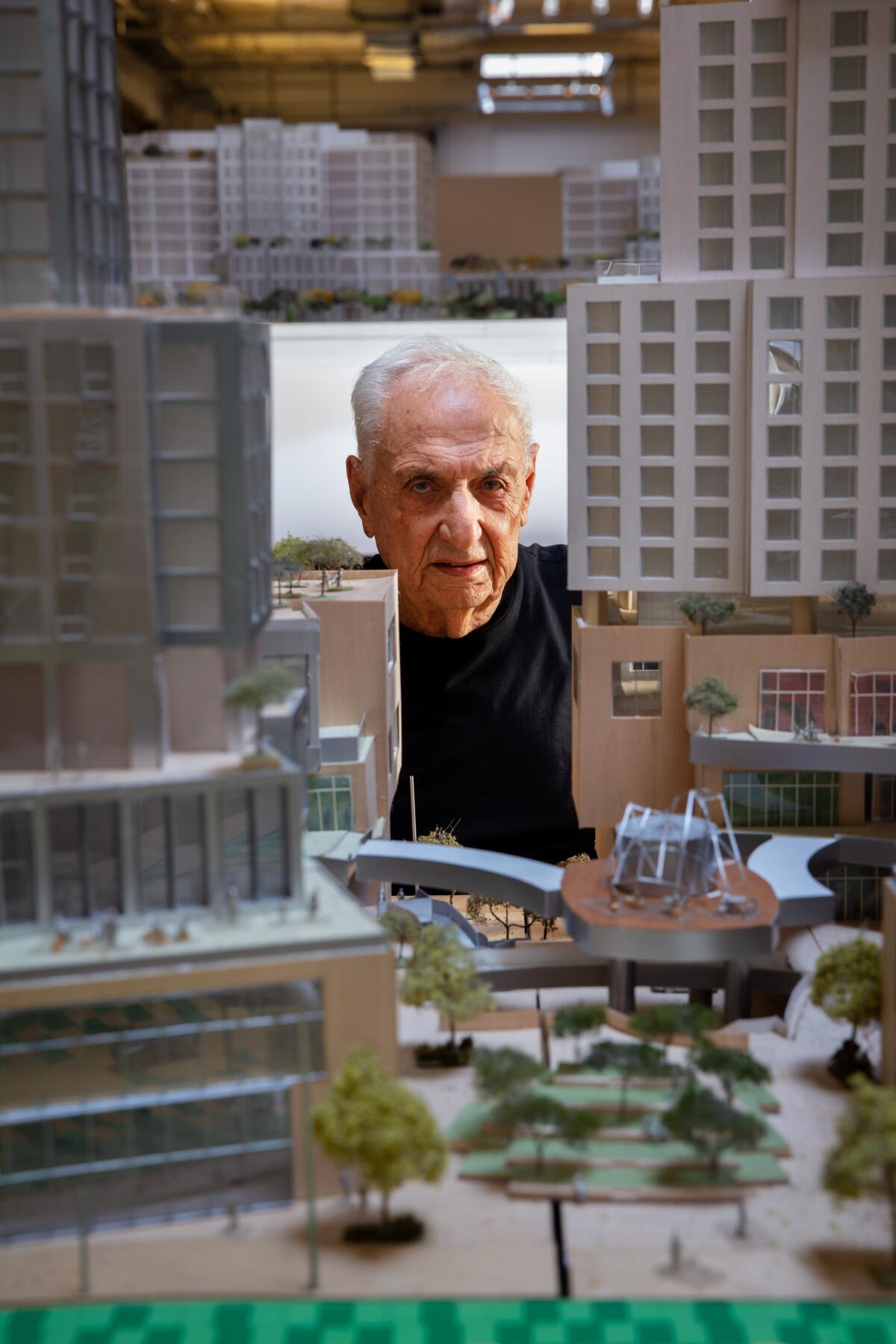

Frank Gehry. Having turned 91 in February, the great L.A. architect who continues to say his best work is ahead of him, is not about to rest on his Disney Hall laurels. This fall he released plans for a fabulous pair of Colburn School concert halls with the potential to make Grand Avenue the arts corridor it is poised to become — if only the clueless Colburn board will, like Borda, move forward, which thus far it has scandalously not. Gehry also has overseen the construction of the Judith and Thomas Beckmen YOLA Center@Inglewood, a stunning home in Inglewood for the L.A. Phil’s essential education program, and he has progressed on an educational arts center that’s part of his L.A. River project.

Tyshawn Sorey. Four summers ago at the Ojai Music Festival, the multi-instrumentalist and composer best known as a jazz percussionist proved that his musical realm extended well into the broad world of modern music. Now there is no stopping him. In November alone, Jennifer Koh was soloist with the Detroit Symphony in the premiere of his violin concerto “For Marcos Balter,” and Seth Parker Woods gave the premiere of Sorey’s moody cello concerto “For Roscoe Mitchell” with the Seattle Symphony. The pandemic forced the cancellation of a major reworking in Paris of Sorey’s “Perle Noire,” a portrait of Josephine Baker conceived by Peter Sellars and featuring Julia Bullock that had its premiere in Ojai, but Da Camera of Houston will put a recent version online Friday.

Vijay Gupta. In any other year the violinist, an electrifying advocate for the homeless and founder of the Street Symphony on Skid Row, would be presiding over his inspirational “Messiah Project” at the Midnight Mission around this time, unleashing the vibrant creative potential in a community we too readily underestimate. But the pandemic hasn’t stopped him from spreading the word. Delivering the 33rd annual Nancy Hanks Lecture on Arts Public Policy, Gupta offered exceptionally powerful examples of how supporting the arts and supporting the homeless, particularly now when the homeless must add the coronavirus to their devastations, improve society when it most needs improving.

Kristy Edmunds. For the head of UCLA’s Center for the Art of Performance, the curtain falling on “Parable of the Sower” was but the prelude to her indomitable dealing with a year-plus intermission from the art of live performance. But the art of performance continues. She has scrupulously filmed a host of artists for inspiring online performances and festivals. She — like Borda, like the L.A. Phil with its YOLA Center and unlike Colburn — also has found in the pandemic opportunity, not obstacle, to continue her Nimoy Theater project, renovating the old Crest Theater in Westwood as CAP UCLA’s new home.

A final note. It seems mean-spirited to follow the occasional Times tradition of ending with a stinker of the year. So in the spirit of a great many others in the arts — and in government (Angela Merkel, take a bow) — who have heroically fought to treat the arts as essential, I’ll just note that it’s not too late for the Colburn board to show crucial foresight as well.

“West Side Story,” “Hamilton,” Laura Linney, Andrew Scott and “What the Constitution Means to Me,” the last of which gave us two reasons to applaud.

More to Read

The biggest entertainment stories

Get our big stories about Hollywood, film, television, music, arts, culture and more right in your inbox as soon as they publish.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.