Commentary: Julia Bullock and Davóne Tines are the must-hear singers of opera today

- Share via

Soprano Julia Bullock included composer Margaret Bonds’ 1942 song “The Negro Speaks of Rivers” in her appearance last week with the Los Angeles Philharmonic at the Hollywood Bowl. She delivered a Langston Hughes line, “My soul has grown deep like the rivers,” and it’s not enough to say she sang the soulful song with soul. In her delivery, she went deeper than mere rivers. She dove down into the darkest, most mysterious depths of an ocean-deep soul.

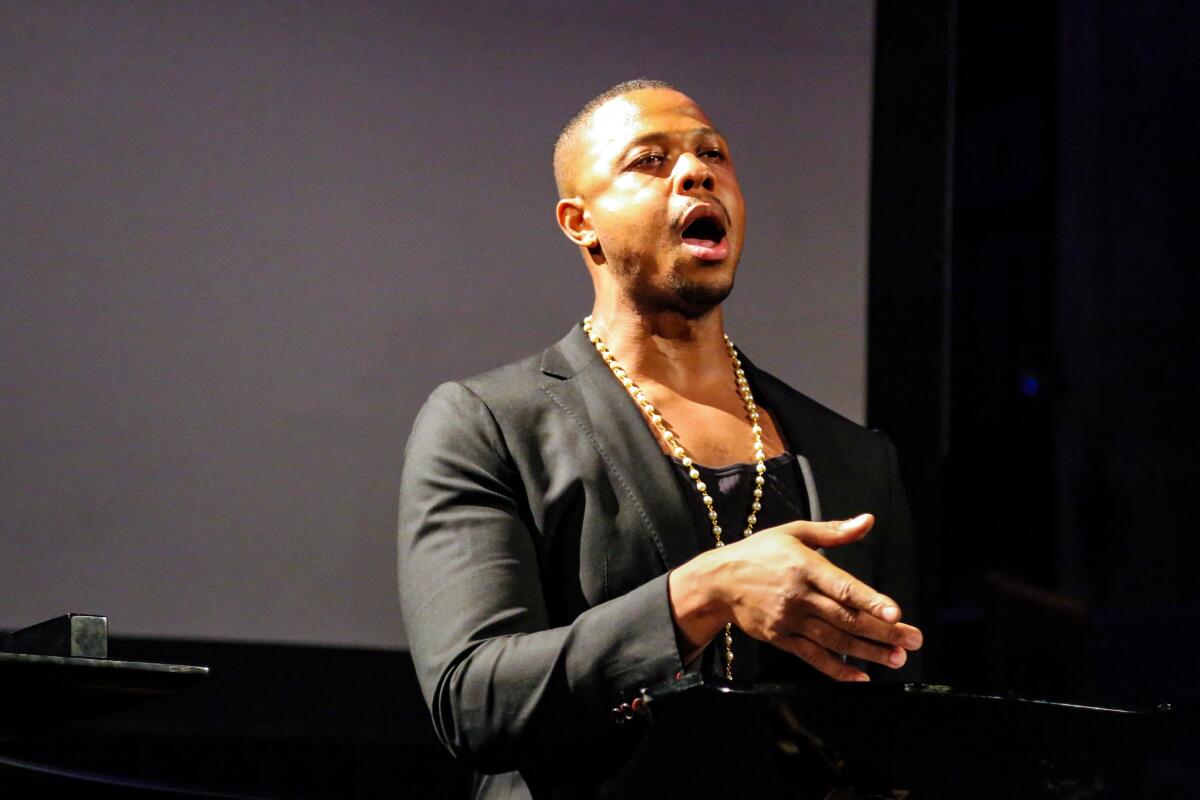

Then this Wednesday, the bass-baritone Davóne Tines included Bonds’ 1925 song “A Brown Girl Dead” in his “Recital No. 1: MASS” at First Congregational Church of Los Angeles. The first of the song’s two stanzas ends, “Death has found her sweet.” Tines wavered on “sweet,” taking all the sugar out of it, ounce by profoundly moving ounce.

In one sense little might seem comparable between Bullock at the Bowl and Tines at First Congregational. Bullock was but part of a program of music by Gershwin and three neglected Black American composers — Bonds, Ulysses Kay and William Grant Still — conducted by Thomas Wilkins. Bullock’s contribution was but five Gershwin and Bonds songs. Elsewhere the program included such popular Gershwin favorites as Robert Russell Bennett’s arrangement of excerpts from “Porgy and Bess” in a “Symphonic Picture” and Variations on “I Got Rhythm” for piano and orchestra that got canceled when the soloist Aaron Diehl had to leave the stage shortly after beginning because he didn’t feel well.

Tines, on the other hand, crafted his “MASS” recital, with pianist Adam Nielsen, as what the singer called a “queering” of the conventional mass. Queering meant the broadest sense of expansion, be it reflection of sexual orientation, of African American tradition or of our relevant present-day spiritual concerns.

With new meditative solo settings of the traditional Latin Mass written for the project by Caroline Shaw, Tines wove Bach, Bonds, Julius Eastman, the percussionist-composer Tyshawn Sorey and spirituals into a newly ordered Kyrie, Agnus Dei, Credo, Gloria, Sanctus and Benedictus. The progress over 50 minutes was from death to life, from dark to light, from heavy to light. This was a solemn, spiritual new music event presented by the Monday Evening Concerts, which has just announced Tines as the long-standing series’ first artist-in-residence.

At the Bowl, the audience picnicked and Bullock was blown up on the big screens aside the famed shell. Tines had the sacred space of a famed old L.A. church. But the differences as experiences weren’t big. It has been increasingly evident that Bullock and Tines are the two singers who can most promisingly bring something powerful, meaningful and even existential to opera.

During the pandemic, both have had a presence online, using the closure of concert halls to search into their roots and their very beings. They are singers who have worked together many times. Both have been mentored by Peter Sellars, who has created exceptional projects for them. They are members of the radical, “discipline-colliding” opera collective AMOC (American Modern Opera Company). They are the two most must-hear singers before the public today. Although just coming into their own, they follow in the footsteps of singers who have mattered most — in particular, Paul Robeson, Marian Anderson, Maria Callas, Lorraine Hunt Lieberson and Jessye Norman.

Like them, they are great singers in the ordinary sense of having a thrilling and distinctive voice, demonstrating impressive technique, projecting text with gripping clarity. They rivet attention. You can’t not listen when they sing. Your mind is not allowed to wander anywhere other than where they intend to take you. But where they take you — that is what makes them not just extraordinary but necessary.

Coronavirus may have silenced our symphony halls, taking away the essential communal experience of the concert as we know it, but The Times invites you to join us on a different kind of shared journey: a new series on listening.

They sing of themselves but not about themselves. I can’t tell you who Bullock is from the way she sang “Summertime,” just that she has done something unique with it. We’ve all heard “Summertime” sung countless times, covered countless ways. There is no right or wrong. It can be a lullaby or lusty. It can flow like thick cream or splash like a jump in the pool. The living can be easy, or not, or every which way.

But when Bullock sang it at the Bowl, she replaced ors with ands. She sang each note like it was its own experience. She caught the big Bowl unawares, and listening was as easy as it was intent. It seemed people couldn’t believe their ears.

Listening to Bonds was not so easy. Bullock caught the fury and also the excitement of the Harlem Renaissance. Context was not explained: Gershwin and Bonds, contemporaries with a shared musical language but not a shared life experience, were heard for dissimilarities of race, gender and privilege — yet also united by something unspoken, something that can only be sung to be taken in.

Tines is as mesmerizing as a singer can be. In his “MASS,” comfort and discomfort are intense. His voice can fill a space and then some, ringing gloriously but also, under pressure, distorting (you might even say queering) the very space he commanded.

His bits of Bach could be like that. Spirituals got distorted, be it through anguish or angelic grace. Unlike Bullock, Tines conveyed the unreconcilable, which is the essence of the spiritual.

Three years ago, for a Monday Evening Concerts program, Tines beautified Eastman’s “Prelude to the Holy Presence of Joan D’Arc” with unearthly poise. The score is nothing more than the intoning of saintly names and the injunction to “Speak boldly when they question you.” There is substantial freedom for the soloist in precisely how to speak or question.

This time, as part of the Sanctus, the Mass’ injunction toward holiness, Eastman channeled what felt like both the rage and the promise of our times, a call to justice and a call for grace, a tear-inducing railing at sanctity and a tearful embrace of it. If Tines had been breathtaking nearly five years ago, then there is nothing in the dictionary to describe the effect he now has on the breath.

His “MASS” can be messy. Our times are messy. Bullock and Tines get that. They’re not the only ones. They are leading a new generation. The future in so many ways does not look bright. In this way, it does.

The Academy Museum of Motion Pictures has opened as the ultimate celebration of Hollywood history, Oscar lore and today’s movie makers.

More to Read

The biggest entertainment stories

Get our big stories about Hollywood, film, television, music, arts, culture and more right in your inbox as soon as they publish.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.