De Wain Valentine, a sculptor of the Light & Space movement, dies at 85

- Share via

De Wain Valentine, a sculptor whose use of unusual industrial materials was instrumental in art’s innovative Light & Space movement in the 1960s and 1970s, died Sunday in Los Angeles. He was 85.

Rather than traditional bronze, Valentine cast abstract sculptures from resin, fiberglass-reinforced polyester and other synthetic materials. Most were pedestal-bound and took simple geometric forms such as disks, rings, pyramids and tapered columns.

Architectural scale occasionally came into play, as in a curved wall of clear resin more than seven feet high and wide. Several wedge-shaped columns in gray, deep blue, lavender, fluorescent yellow and other lollipop hues stand as much as 12 feet tall.

Light permeating the clear plastic wall made the surface perceptually porous, creating a tactile optical effect in the space around the sculpture almost like a frozen waterfall. The columns taper as the shape rises toward the top, where the increasingly transparent color becomes ethereal; dense, more opaque color below makes the airy form appear tethered to the floor by a great visual weight.

“From Start to Finish: De Wain Valentine’s ‘Gray Column,’” an exhibition organized by the Getty Conservation Institute and the J. Paul Getty Museum for the citywide Pacific Standard Time festival in 2011, chronicled the arduous process of fabricating a freestanding, 8-foot-wide slab. The massive sculpture, which required invention of a new polyester resin that would not crack or buckle when poured in large volumes, took nearly two years to produce (1975-76). The ingenious material, developed with Hastings Plastics Co. in Santa Monica, is now called Valentine MasKast Resin.

“L.A. is the city of the modern world so far,” Valentine told UCLA art historian Kurt von Meier in a 1966 interview in Artforum, “and that world is going to be plastic.”

Most of Valentine’s resin sculptures required a four- or five-step process. First, a mock-up of the sculpture was shaped, usually from light polyurethane foam. The mock-up became a pattern, coated in fiberglass or plastic. When the coating set and was removed from the pattern, the mold that resulted was used to cast the sculpture with pigmented liquid resin. Removed from the mold, the final piece was sanded and polished to a high sheen.

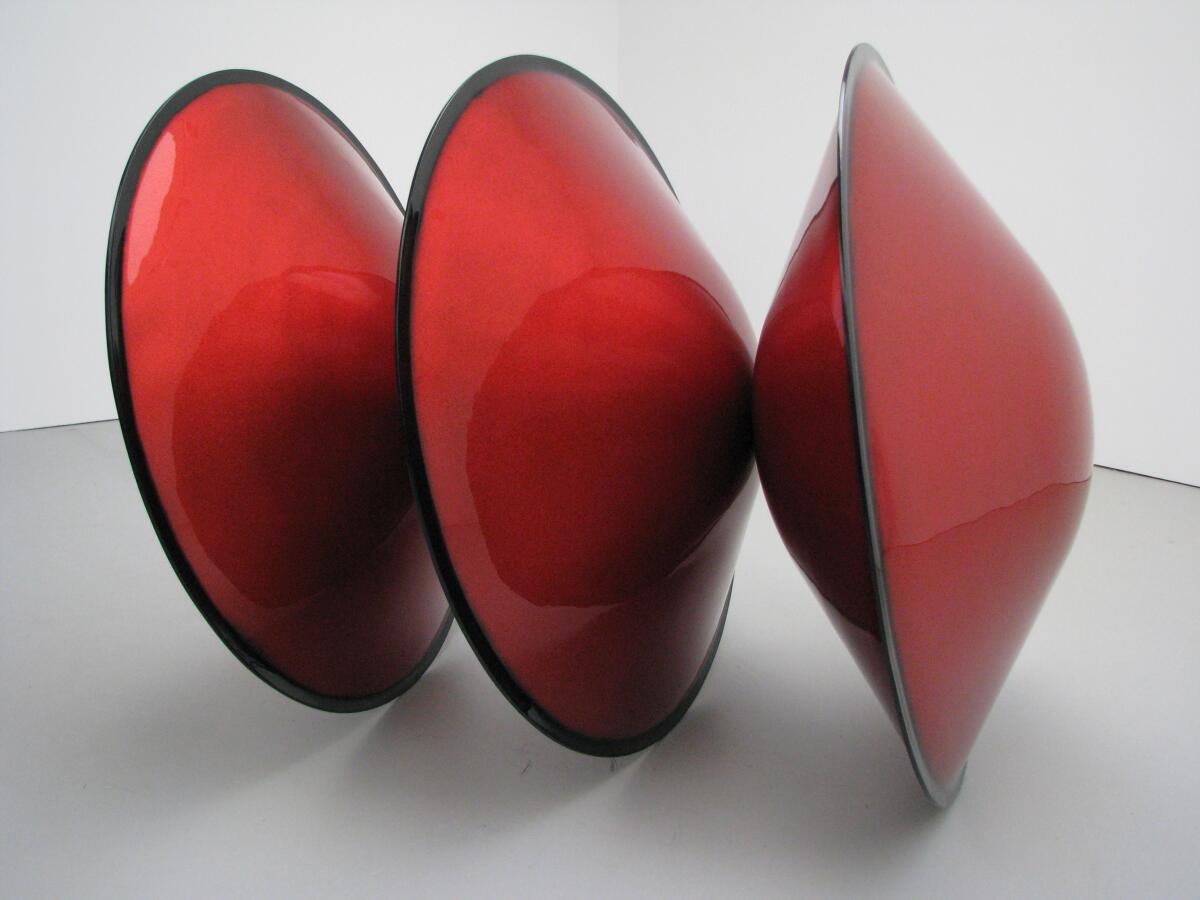

Some Valentine sculptures are less labor-intensive and more playful. “Triple Disk Red Metal Flake — Black Edge” (1966), now in the collection of New York’s Museum of Modern Art, consists of a tilted trio of crimson flying-saucer shapes balanced on their edges. “Double Top” (1967), in the collection of the Los Angeles County Museum of Art, is a back-to-back pair of the bulbous children’s toys in vibrant red and blue. The voluptuous and tumescent forms convey a subtly erotic dimension.

Related works are in the collections of the Whitney Museum of American Art and the Museum of Contemporary Art, Los Angeles. These waist-high sculptures are made from fiberglass-reinforced polyester. Their highly polished surfaces are reminiscent of the flashy custom cars the artist saw — and sometimes helped paint — in his father’s automotive shop during his youth.

Valentine was born Aug. 27, 1936, in Fort Collins, Colo. (His Danish great-grandfather emigrated to the state to prospect for gold.) After receiving a B.A. in art from the University of Colorado in 1958, and before completing an MFA two years later from the same school, where he would later teach, he enrolled in the intensive summer program at Yale Norfolk School of Art in Connecticut. In Denver he worked with Abstract Expressionist painter Clyfford Still, and at Yale he worked with painters Richard Diebenkorn and Philip Guston. All were adept with color abstraction.

A part-time teaching position at UCLA brought Valentine to California in 1965 with his wife and three small children. Landing in Venice Beach, then a down-and-out seaside neighborhood with cheap studio space and a nascent community of ambitious young artists, he had the luck to rent a place next door to sculptor Larry Bell. Before the month was over, he had met Bell’s close friend, Frank O. Gehry. Bell’s artistic interests and Gehry’s developing architecture practice meshed with Valentine’s own blossoming pursuits.

Over the years, he acquired several ramshackle Venice buildings, including his original 5,000-square-foot studio. Following a divorce, Valentine lived for several years in Hawaii. There he met his wife, Kiana Sasaki, who survives him.

Valentine acknowledged an affinity with the Southern California sculptures and paintings of Bell, Billy Al Bengston, Robert Irwin and John McCracken, contemporaries for whom a precision surface was key to a successful work of art. Former Los Angeles Times art critic William Wilson first used the term “finish fetish” in 1966 to describe the look. New York sculptors Dan Flavin, Donald Judd and Robert Morris were also influential, as were such historical figures as Albert Pinkham Ryder and J.M.W. Turner.

Valentine’s first solo exhibition in Los Angeles was at Ace Gallery in 1968. He later showed in L.A. with Virginia Dwan Gallery. In New York he showed at David Zwirner Gallery in 2010 and 2015 and at Almine Rech Gallery in 2017.

In the late 1970s, concerned about the toxic effects of working with resin, Valentine stopped using the chemically volatile material. Still interested in the effects of light, color and surface, he made an extensive series of skeletal wall reliefs and free-standing sculptures from bonded strips of pale blue-green glass. They were shown in a 1979 solo exhibition at LACMA.

More to Read

The biggest entertainment stories

Get our big stories about Hollywood, film, television, music, arts, culture and more right in your inbox as soon as they publish.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.