Review: As drought deepens, nine L.A. artists think about water

- Share via

The small, unassuming wall relief at the entrance to “Confluence,” a modest but timely exhibition at Track 16 on the theme of water issues related to the Los Angeles River, turns out to be emblematic of what follows.

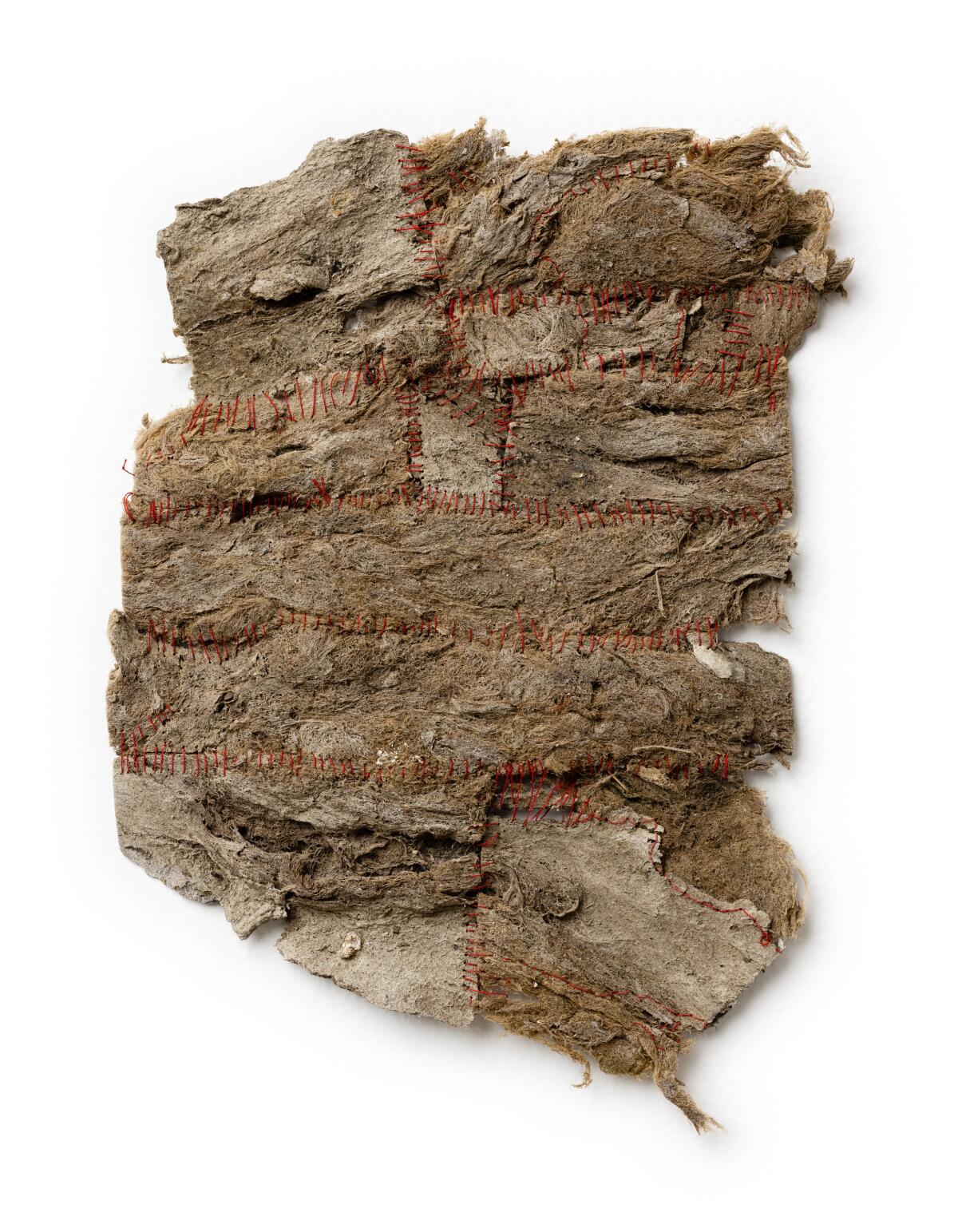

For “L.A. River Paper,” artist Emma Robbins gathered slight fragments of matted algae, leaves and bird material from the water, then stitched the fuzzy pieces together with reddish thread into an irregularly shaped sheet. This is handmade paper that merges natural formation and artistic intervention — a confluence, in other words. The word describes both the general process of separate things coming together and — notably — the specific junction of two rivers.

What is the other river coursing through Robbins’ “L.A. River Paper”? A compelling video by AnMarie Mendoza suggests a provocative answer: a river of humanity.

“The Aqueduct Between Us,” a 39-minute oral history, features water images around the city, including natural streams; the concrete flood-control channel that runs from the San Fernando Valley to the sea; the elegant fountains in front of the sleek Department of Water and Power building, the 1965 downtown landmark designed in a corporate international style by A.C. Martin and Associates that is high on any list of great modern architecture; and sections of the century-old engineering marvel that is the Los Angeles Aqueduct. Stitched together, they picture the essential liquid foundation for human existence in the city.

And, not so incidentally, for slow-moving ruin.

Almost the entire state of California is now ranked as experiencing severe, extreme or exceptional aridity, the three worst levels charted by the National Drought Mitigation Center at the University of Nebraska. We aren’t just in a drought, we’re in a megadrought.

An exhibit at Track 16, ‘Confluence,’ by nine mixed media artists, explores a range of water issues from communities fighting for survival, water scarcity resulting from infrastructure and climate change.

Water imagery in the video is interspersed with short, pithy interviews with numerous Indigenous residents, mostly Tongva and Paiute. “Water is life,” they repeat — a simple, imperishable chorus that resounds against the more than two decades of Southern California drought that is steadily building toward epic disaster. In Mendoza’s marvelously incisive video (also available on YouTube) the near invisibility of Indigenous people today in a place where genocide was launched more than 175 years ago merges with the typical inconspicuousness of critical water issues from city dwellers’ daily consciousness.

“Confluence” was ably organized by artist Debra Scacco, whose contribution is a drawing made from ink and water. Its abstract, marbled linearity is composed from an interaction with wind, which moved the liquid materials around on the sheet until they dried. Like Robbins’ paper, it’s one of several works that turn on related actions between artist and natural forces.

Lauren Bon assumes a not dissimilar approach in a composition formed from an evaporated puddle of rainwater on a sheet of black foil. The whitish residue leaves a mottled imprint. Circular and spotted markings evoke a sky map — loosely, the place where the rain came from.

Bridget DeLee’s “InBetween” likewise crosses territories. Suspended horizontally from the ceiling, the base of a palm leaf (called a crownshaft) is punctured by long braids of black synthetic hair, which are held in place by wooden pony beads. The fashionable strands hold up a second leaf suspended below the first, then cascade through it to the floor. The leaves and the braids create an intersection of crowns, one naturally occurring and the other culturally produced.

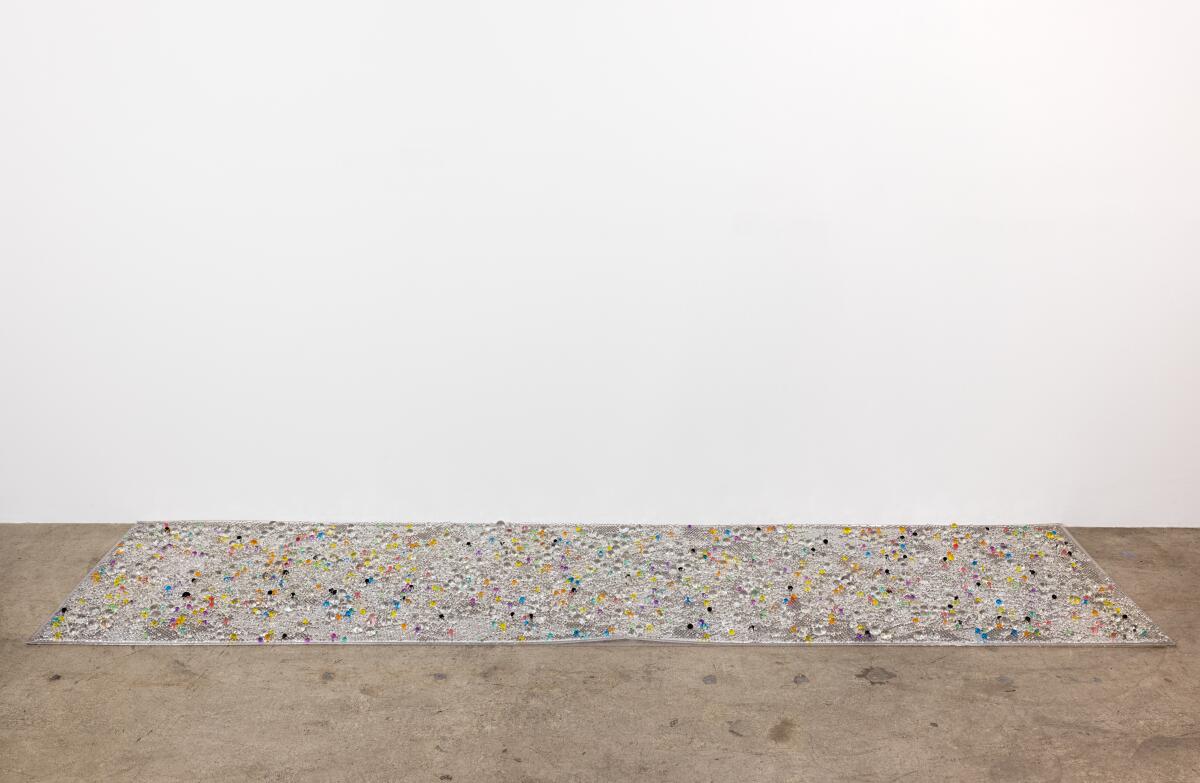

Kori Newkirk, one of two men among the show’s nine artists, soaked super-absorbent polymer beads, the kind used in vases to keep floral arrangements from wilting, in river water, then spread them in a thin layer atop a clear vinyl sheet spread out on the floor. The moisture is slowly evaporating from the beads as the show continues, leaving intertwined bits of shifting sediment behind — a river-made Pollock drip painting, as it were.

In Newkirk’s floor piece, color seems to have been leeching out of the polymer beads as they dry up. Elsewhere, a general absence of color marks these works, which rely on neutral tones. The absence is itself a residue, the remains of an established tradition that has set aside color’s irrational pleasures to signify seriousness in art ever since Conceptualism emerged into prominence in the 1970s.

Fragments of color do turn up entangled in the materials of Blue McRight’s “Night Dive,” a suspended assemblage of ropes, pulleys, a chunky metal hook and incongruous plastic netting and hair-scrunchies woven into decorative tiers. It’s like a sculptural salvage-job after trawling through a sludge of ocean detritus — festive streamers recovered from waste.

And color is of course integral to Lane Barden’s fascinating grids of documentary aerial photographs, which appear to have been shot from a drone. His pair of grids starts at the upper left with a bright green athletic field in the San Fernando Valley and, picture by picture, follows the contested river’s circuitous urban path through four dozen aerial images, which finally empty into the cerulean Pacific Ocean at the lower right.

The primary exception, though, is Alicia Piller’s entrancing “Extinctions,” a sculpture whose palette of red, white and blue is clearly not accidental. The central element is a toy-like wooden rifle jammed upright through a shark’s gaping skeletal jaw. Layered strips of vinyl and leather drape from the top, which is roughly the height of a standing person, bunching into turbulent swirls around the bottom. The textiles, dotted with human teeth and flaccid balloons, are embalmed in clear, glistening resin that holds it all in place.

Piller works from material accumulations of cast-off stuff, and her composition swings between microscopic and macroscopic in a manner loosely reminiscent of Elliott Hundley’s work. The rifle, pointedly described in the object’s list of materials as colonial in style, glances off Native American genocide; the shark’s jaw ricochets off ongoing ocean annihilation, with more than a quarter of those fish currently facing eradication, according to the World Wildlife Fund. While Los Angeles staggers through its driest 23-year period in 1,200 years, the sculpture is a disconcertingly festive maypole that is simultaneously brutal and sad.

All is not lost. Putting the sculpture’s title, “Extinctions,” in the plural adds a queasy sliver of future continuity. As they say, the Earth doesn’t much care about climate change, as it will merely slough off humankind and continue on its way. Megadrought be damned.

'Confluence'

Where: Track 16, 1206 Maple Ave., No. 1005, Los Angeles, CA 90015

When: Wednesday to Saturday, 12 p.m. to 6 p.m. and by appointment. Closed Sunday - Tuesday.

Info: (310) 815-8080, track16.com

More to Read

The biggest entertainment stories

Get our big stories about Hollywood, film, television, music, arts, culture and more right in your inbox as soon as they publish.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.