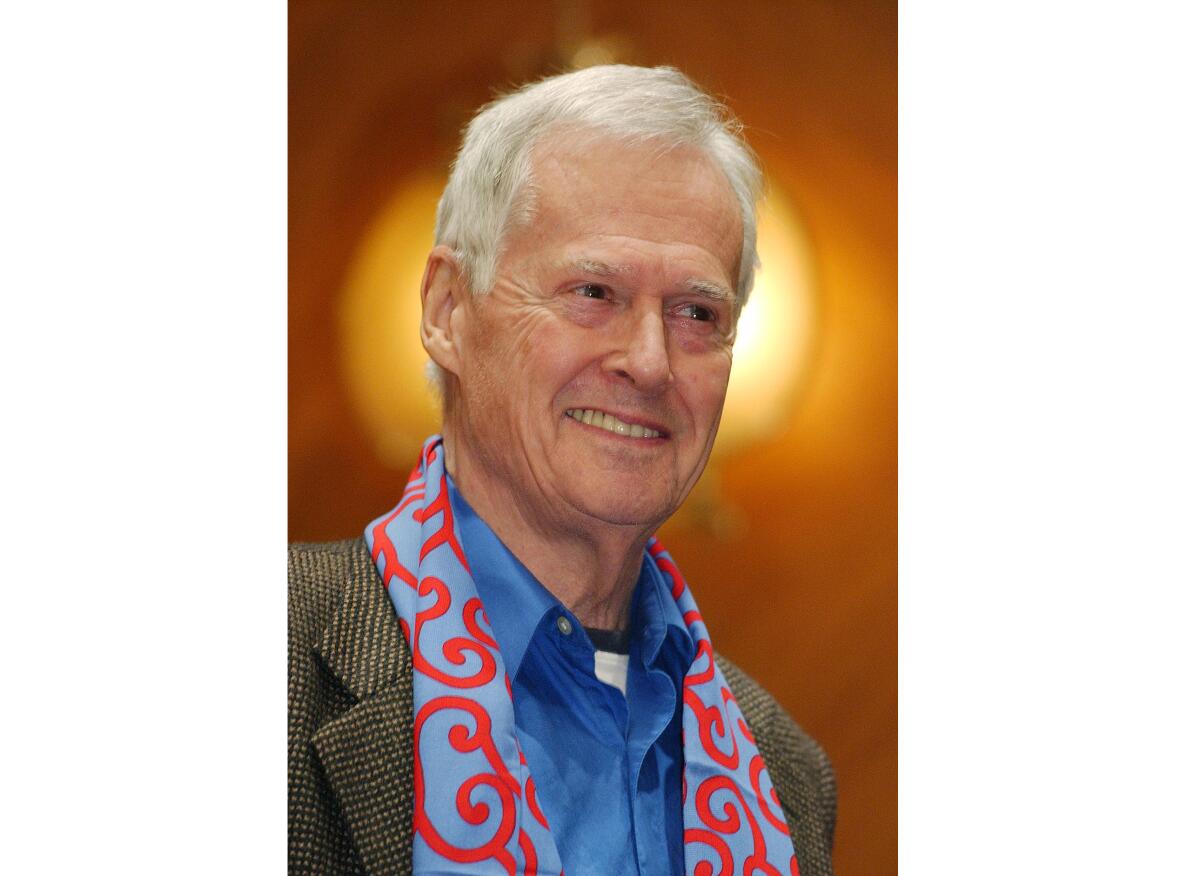

Ned Rorem, prize-winning composer and writer, dies at 99

- Share via

NEW YORK — Ned Rorem, the prolific Pulitzer- and Grammy-winning musician known for his vast output of compositions and for his barbed and sometimes scandalous prose, died Friday at 99.

The news was confirmed by a publicist for his longtime music publisher, Boosey & Hawkes, who said he died of natural causes at his home on Manhattan’s Upper West Side.

The handsome, energetic artist produced a thousand-work catalog ranging from symphonies and operas to solo instrumental, chamber and vocal music, in addition to 16 books. He also contributed to the score for the Al Pacino-starring film “The Panic in Needle Park.”

Time magazine once called Rorem “the world’s best composer of art songs,” and he was notable for his hundreds of compositions for the solo human voice. The poet and librettist J.D. McClatchy, writing in the Paris Review, described him as “an untortured artist and dashing narcissist.”

His music was mostly tonal, though very much modern, and Rorem didn’t hesitate to aim his printed words at other prominent contemporaries who espoused the dissonant avant-garde, like Pierre Boulez.

“If Russia had Stalin and Germany had Hitler, France still has Pierre Boulez,” Rorem once wrote.

He had a basic motto for songwriting: “Write gracefully for the voice — that is, make the voice line as seen on paper have the arched flow which singers like to interpret.”

Rorem won the 1976 Pulitzer for his “Air Music: Ten Etudes for Orchestra.” The 1989 Grammy for outstanding orchestral recording went to the Atlanta Symphony for Rorem’s “String Symphony, Sunday Morning, and Eagles.”

His 1962 “Poems of Love and the Rain” is a 17-song cycle set to texts by American poets; the same text is set twice, in a contrasting way.

Born in Richmond, Ind., Rorem was the son of C. Rufus Rorem, whose ideas in the 1930s were the basis for the Blue Cross and Blue Shield insurance plans and who turned to Quaker philosophy, raising his son as a pacifist.

The younger Rorem went to day school at the elite University of Chicago Laboratory Schools. By the time he was 10, his piano teacher introduced him to Debussy and Ravel, which “changed my life forever,” said the composer whose music was tinged with French lyricism.

He went on to study at the American Conservatory of Music in Hammond, Ind., and Northwestern University in Evanston, Ill., then the Curtis Institute in Philadelphia and the Juilliard School in New York.

As a young composer in the 1950s, he lived abroad for eight years, mostly in Paris but with two years in Morocco.

“The Paris Diary” covers his stay there and is filled with famous names of people he met — Jean Cocteau, Francis Poulenc, Balthus, Salvador Dali, Paul Bowles, John Cage, Man Ray, and James Baldwin. The late writer Janet Flanner called it “worldly, intelligent, licentious, highly indiscreet.” Rorem himself said his text was “filled with drunkenness, sex, and the talk of my betters.”

His literary self-portrait continued, contained in “The New York Diary,” “The Later Diaries” and “The Nantucket Diary.”

“His essays are composed like scores,” McClatchy once wrote of him. “The same hallmarks we listen for in Rorem’s music will be found in his essays as well: indirection, instinctive grace, intellectual aplomb, a lyrical line.”

Some were appalled by Rorem’s notorious accounting of his relationships with four big-name men in music: Leonard Bernstein, Noel Coward, Samuel Barber and Virgil Thomson. He also outed a few others.

But most of his private life was centered around James Holmes, an organist and choir director with whom he lived for three decades in New York City. Holmes died in 1999. A statement from Boosey & Hawkes said Rorem died surrounded by friends and family and is survived by six nieces and nephews and 11 grandnieces and grandnephews.

Drawing on his upbringing, Rorem based his “Quaker Reader” — a collection of pieces for organ — on Quaker texts.

As for his non-musical writings, he said: “My music is a diary no less compromising than my prose. A diary nevertheless differs from a musical composition in that it depicts the moment, the writer’s present mood which, were it inscribed an hour later, could emerge quite otherwise.”

Rorem’s essays on music appear in anthologies titled “Setting the Tone,” “Music from the Inside Out,” and “Music and People.”

“Why do I write music?” he once asked. “Because I want to hear it — it’s as simple as that.”

More to Read

The biggest entertainment stories

Get our big stories about Hollywood, film, television, music, arts, culture and more right in your inbox as soon as they publish.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.