Commentary: After six years away, Gustavo Dudamel returns to a changed Venezuela

- Share via

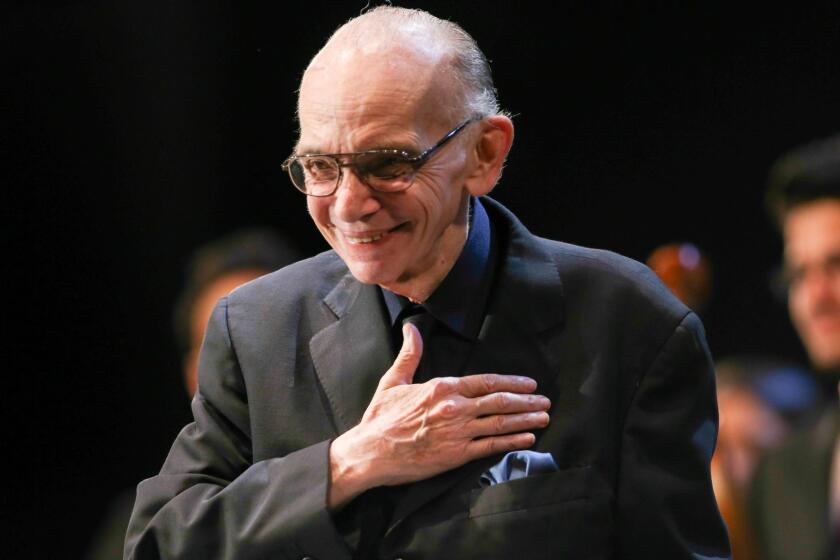

“For me, I had that need to connect with my soul. I was floating.”

Just back in Los Angeles, Gustavo Dudamel is sitting on the sofa in his office at Walt Disney Concert Hall. It is late afternoon. He has been brought a cappuccino after leading a demanding double Los Angeles Philharmonic rehearsal — the third act of “Tristan und Isolde” in the morning; and music from the “The Nutcracker,” with nods to both Tchaikovsky and Duke Ellington, after lunch.

Dudamel could be speaking, then, of his long obsession with Wagner’s opera, which transcends time and space and which he is finally conducting for the first time this weekend with his Los Angeles Philharmonic. He could, as well, be referring to a ballet he has long delighted in bringing to children and that is also on the L.A. Phil holiday plate. “I have part of my soul here,” Dudamel explained, “and other places.”

“But my country, my people are my real soul, and, yes, I made that decision to go.”

Dudamel had just returned from his home town of Barquisimeto, where he hadn’t been in 11 years. This was also his first trip to Venezuela in six years. Inciting the wrath of President Nicolás Maduro, Dudamel had become politically persona non grata after speaking out about the violence and repression he felt was not being addressed by the government during a period of widespread demonstrations in the country.

“I went to see the children,” he continued, those countless music students in the country’s famed El Sistema music education program. “That fact that it has been 11 years since I was Barquisimeto,” where Dudamel had his first music lessons in a local El Sistema center more than three decades ago, “is a really long time. I had to go.”

Gustavo Dudamel may have been in Hollywood on Tuesday receiving his star on the Walk of Fame, but in his comments during the ceremony and in an interview afterward, he showed his heart was in his native Venezuela, which is bracing for massive anti-government demonstrations.

Although Dudamel has officially retained his title of music director of El Sistema and has stayed in touch through almost daily online meetings and coaching, thus remaining the symbol of El Sistema inside Venezuela and internationally, he says that “the children had to see that I’m there for them, that I’m not only an idea.”

Without going into details, Dudamel merely acknowledged that the political situation has improved in Venezuela to the point where he was now welcome in country. He had further impetus from his wife, Spanish actress María Valverde, who has been inspired to make a documentary on Barquisimeto’s White Hands Choir, the chorus of deaf and hard-of-hearing children in El Sistema, after seeing them in the revelatory L.A. Phil/Deaf West Theatre production of Beethoven’s “Fidelio” that Dudamel led at Disney in April.

Dudamel said he intentionally kept his trip low-key. He arrived at El Sistema centers in Barquisimeto and Caracas unannounced. He only led rehearsals, no public concerts. He spent much time consulting with El Sistema faculty and administrators. He caught up with family and friends. He couldn’t hide and didn’t try to. But there was no publicity.

“I went to dinner in my town,” he said of a typical incident. “I was wearing a Cardenales baseball cap, my team, and a mask. The waiter kept coming to the table and turning and looking at me, on one side and then the other side. It was so sweet. I took off my mask and said, ‘Yes, it’s me.’

“But this was not about recognizing me. It was about recognizing the achievements of El Sistema.”

Among the startled students, Dudamel was inevitably treated like a rock star. “But I can be honest with you,” he confessed, “and say that the first days were complex.” Barquisimeto, where he spent most of his trip with just three days in the capital, Caracas, had changed. Many of his friends and family had left, some had died of COVID-19, and a whole new generation had arrived at El Sistema.

The loss of loved ones to the pandemic has given Gustavo Dudamel a fresh outlook on the L.A. Phil, his new post in Paris, and his life with his wife and son.

What else had changed was the level of playing. For Dudamel, this confirmed the success of what he emphasized was the mission of his mentor and Sistema founder, José Antonio Abreu, who died in 2018.

“Maestro Abreu said something that was very important,” Dudamel noted. “We are always achieving at a better level.”

José Abreu, the globally acclaimed founder of Venezuela’s El Sistema youth orchestra, a project that offered thousands of poor children free music education, died Saturday.

At this point, Dudamel pulls out his cellphone and shows a video of him rehearsing the National Youth Orchestra of Venezuela, made up of players between the ages of 8and 14, tackling music from John Williams’ “Jurassic Park.” “It’s unbelievable!” he exclaimed. It is unbelievable. A trombonist so small he has to stand on a chair to see the conductor is riveting. Dudamel said he sent the video to an astonished Williams.

El Sistema has seemingly survived Venezuela’s severe economic crises and continued to rise above politics. Dudamel emphasized that regimes across the political spectrum that want to take credit for a popular program that reaches upward of a million students a year, the vast majority of them underprivileged. An El Sistema mantra is that music education is a human right, and it was, at Abreu’s insistence, written into the Venezuelan constitution.

“Even with the difficulties of access to materials and all of that,” Dudamel said he found, “the children keep playing and they keep building their instruments. It was like, ‘Wow, my God, Maestro Abreu is alive!’”

But Dudamel said the real revelation for him was that “in the end, what I saw in my country is that people are tired of politics. They don’t want to talk about politics anymore. They are tired of fighting.”

That’s not to say there isn’t still bitter opposition to the current regime of a strong-arm leader. That is not to say that the country does not continue to face consequential economic hardship. But Dudamel said that many Venezuelans who had left the country are now returning, and that includes former members of El Sistema and of its famed Simón Bolívar Symphony Orchestra, which Dudamel said he led in two rehearsals, finding old faces and new.

To help celebrate his return to his old orchestra, Dudamel has just announced that he will release complete videos of Beethoven’s nine symphonies performed by the Bolívars in Barcelona in 2017, free of charge. These are among the last of his public performances with his orchestra.

“I was recharged by all of this being in Venezuela,” Dudamel continued, and that included that fact that having a public agenda also allowed him time for quiet. “I was studying a lot. There was the possibility to be with people but also to be alone in my air, my oxygen, in the place where I was born.

“And I was working on ‘Tristan’ in Barquisimeto like crazy. It’s an Everest!”

It’s an Everest that Dudamel had been trying to climb since he was in his mid-20s. Now he has begun the ascent for real from his home base, although the preparation has been going on for as long as we have known him. The same year that Dudamel made his American debut with the L.A. Phil at the Hollywood Bowl, the summer of 2005, Dudamel became Daniel Barenboim’s assistant at the Staatsoper Berlin.

Venezuelan Gustavo Dudamel, 24, commands attention.

“I remember sitting with Barenboim at the podium for a complete performance of ‘Tristan,’” Dudamel recalled. “He said, ‘Do you want to sit with me in the podium?’ And I said, ‘Yes.’

“I was sitting for five hours in the pit next to him, looking at the score, looking at him, looking at the musicians. That was my first experience with ‘Tristan.’

To Barenboim’s astonishment, Dudamel wanted to sit in the pit the second night and the third. “It was the music!”

To describe what it was like in the pit, Dudamel crouches down on his couch. Whenever Barenboim wanted to acknowledge the applause of the audience, he had the orchestra pit rise, which meant his young assistant would hide by lying down on the floor at the players’ feet. “The musicians,” he joked, “were like, ‘who is this guy?’”

It turns out that 2005 was also the first time Dudamel saw the “Tristan Project,” which he has now inherited. In 2004, then L.A. Phil music director Esa-Pekka Salonen, director Peter Sellars and video artist Bill Viola created a quintessential L.A. “Tristan.” It was semi-staged in Disney Hall and then given a full opera-house staging at the Paris Opera the following year. This was also Dudamel’s first time at the Opera Bastille, the company’s newest opera house, not knowing that he would one day not only succeed Salonen in L.A. but go on to be newly appointed music director Paris Opera as well.

Any serious Wagnerian can find grumble material in the new production of “Tristan und Isolde” introduced by the Music Center Opera Sunday afternoon.

In January, Dudamel will follow the L.A. Phil “Tristan Project” with the opera version with his French company at the Bastille. To Dudamel this is not so much coincidence as fate. The opera is simply, by now, he feels, in his blood. “I don’t know about previous life or after life. But I feel like this is something that I did,” he said.

After that last performance in Paris on Feb. 4, the French company will retire its 18-year-old production. But the orchestra version can continue indefinitely. Salonen has the hope to bring it to the San Francisco Symphony, of which he is now music director.

“One day I would like to bring the ‘Tristan Project’ to Venezuela,” Dudamel said. “It would be great to play it with a youth orchestra. I think ‘Tristan’ with a youth orchestra could be a transcendental thing. One day, maybe in the future.”

'The Tristan Project'

What: Gustavo Dudamel conducts “The Tristan Project”

When: 8 p.m. Friday, Saturday, Dec. 15, 16 and 17; 2 p.m. Sunday

Tickets: $64 - $216

Info: (323) 850-2000, laphil.com

More to Read

The biggest entertainment stories

Get our big stories about Hollywood, film, television, music, arts, culture and more right in your inbox as soon as they publish.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.