Could Tchaikovsky’s music spur a ‘full body orgasm’? A brief history of surprising orchestra reactions

- Share via

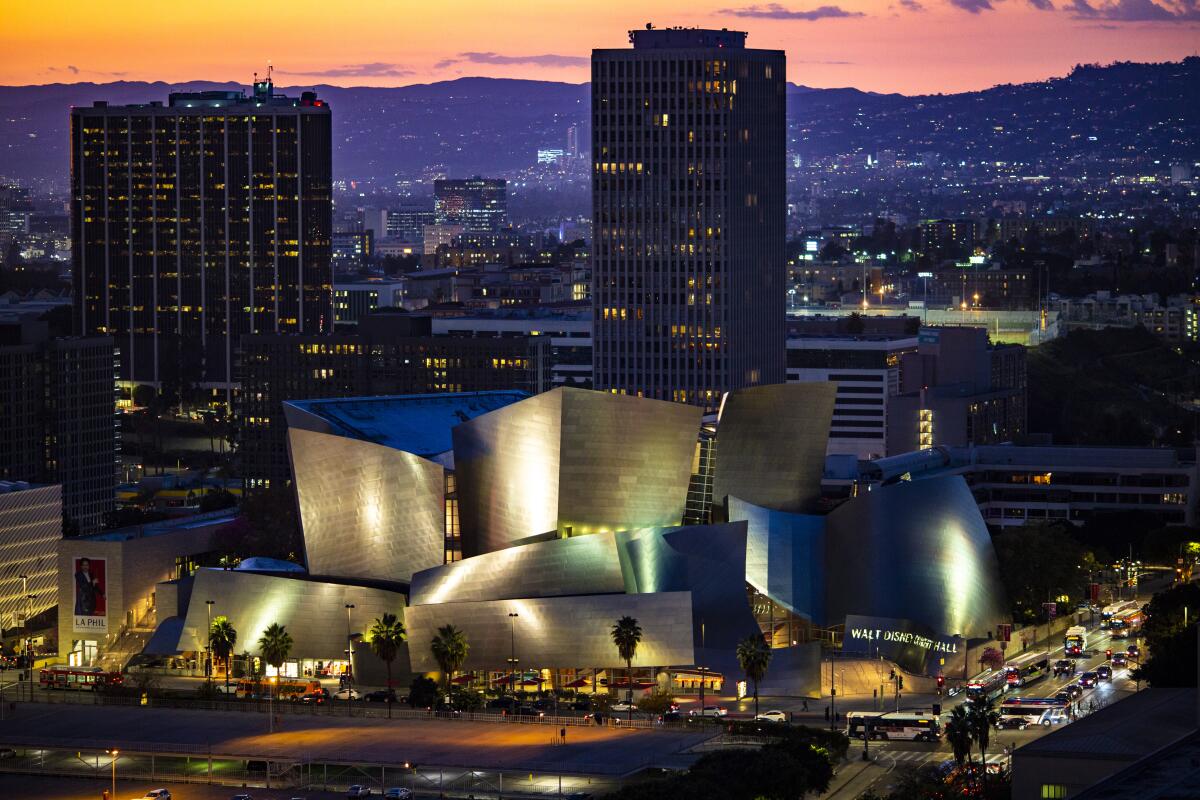

Audience members at the Los Angeles Philharmonic’s performance of Tchaikovsky’s Fifth Symphony late last month were surprised by an abrupt noise in the middle of the second movement. After one audience member tweeted that the sound was of a person having a “loud and full body orgasm,” the alleged moan got audiences talking outside Walt Disney Concert Hall.

So much so that Overheard L.A. even created its own merchandise about the incident — which was removed within hours. “Come for the music stay for the standing O,” the shirts read.

The source of the sound remains the subject of debate. Some in the audience thought the noise resembled a person waking up suddenly, or a small jump scare. Others suspect that it might have stemmed from a medical condition or issue. Either way, this isn’t the first time in history that a musical performance has inspired a rousing reaction in audience members.

Multiple people reported hearing someone ‘orgasm’ during the L.A. Philharmonic’s performance of Tchaikovsky’s Fifth Symphony on Friday. It’s not clear what happened.

“He [Tchaikovsky] would’ve been thrilled at that audience reaction at the L.A. Philharmonic,” jokes Adrian Spence, the artistic director of the chamber music organization Camerata Pacifica.

Spence describes Tchaikovsky’s symphonies as “extremely emotional” as the late composer wrote with his “heart on his sleeve.” The evidence, he notes, is in Symphonies number four, five and six.

According to Spence, the Fourth Symphony is “bombast,” while the fifth is filled with romance and the sixth plumbs sorrow. He says Tchaikovsky’s emotionally charged works were the standard for the 1800s-era Romantic period — a time that followed the Classical and Baroque periods that gave rise to more “objective” composers like Johann Sebastian Bach and Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart.

“That music was not written to elicit emotional reaction,” Spence says. “That was written very objectively and, especially with Bach, the beauty is in the form, structure or the writing.”

That changed with Ludwig van Beethoven.

“Beethoven was intentionally trying to elicit an emotional response, or he was intentionally writing — in his music — the layers of feelings that we have, all the confusion and the contradictions of feelings that we have,” Spence says.

But could Tchaikovsky’s Fifth brim with such stirring elements that it could elicit an orgasm? Probably not, says UCLA professor of musicology and comparative literature Tamara Levitz. “I suspect the person was doing something,” Levitz says.

Still, Levitz explains that recent studies, which investigate the ways music can promote physical and psychological health, suggest that “it could be the harmony, it could be the tambor, it could be the actual performers and how they were playing” that inspires more animated reactions from listeners. Spence notes that past studies have found that people’s physiologicial responses, including heart rate, shift when listening to classical music.

But audiences’ responses to classical music also led to a sexist debate concerning “women’s hysteria” in the 1800s, Levitz says. “They didn’t want women hearing this music,” particularly by Richard Wagner, she notes. According to “The Piano Plague: The Nineteenth-Century Medical Critique of Female Musical Education” by James Kennaway, 19th-century psychologists and gynecologists shared concerns about women listening to too much music in fear of supposedly overstimulating the nervous system. This way of thinking kept women from concerts and music education. The research happening today, which focuses on the neurochemistry of music and the body, veers away from this sexist ideology.

Yet spirited audience reactions, particularly in theater and dance spaces, have been common and even expected for centuries. Performances at Shakespeare’s Globe were riddled with shouts and people in the yard (or pit), for instance, throwing food on stage. There’s a long history of audience members booing at operatic performances, particularly in Europe. “By the end of the 19th century, audiences were pretty quiet,” Levitz says.

Which means sitting in complete silence while taking in a theatrical performance is a fairly new phenomenon.

“Audiences that came to us out of the 20th century have been highly conditioned to listen to the music of the 18th and 19th century, to the point that their minds are somewhat closed,” Spence says.

Regardless of what transpired at the L.A. Phil, the incident raises larger conversations about our connection to music and its evolving culture. In “What Makes an Audience? Investigating the Roles and Experiences of Listeners at a Chamber Music Festival,” Stephanie E. Pitts, Professor of Music Education at the University of Sheffield, suggests that our evolving listening practices have changed how we behave at concerts.

These days, the life of a composition lives beyond the chamber or concert hall. It is also on our phones. The accessibility of music rings in younger and more diverse audiences that are challenging the traditional, reserved behaviors of listening to music, Spence says. “How they’re willing to experience music is opening up,” he adds.

More to Read

The biggest entertainment stories

Get our big stories about Hollywood, film, television, music, arts, culture and more right in your inbox as soon as they publish.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.