‘Carnival Row’ is not the next ‘Game of Thrones.’ Its showrunner wouldn’t have it any other way

- Share via

Writer-producer Marc Guggenheim is launching Amazon’s epic fantasy drama, “Carnival Row,” starring Orlando Bloom. He’s also on the verge of wrapping up one of the CW’s popular superhero shows, “Arrow.” But he’s quick to point out he should be a lawyer right now.

He had been, for some years, working as a commercial litigator. But what began as an unexpected favor — while in law school at Boston University, his brother, Eric, then in film school at New York University, asked him to help write a couple of scripts — turned into a sustained interest as he became disillusioned with the legal system and his competence.

“I was 29 years old. I was in my fifth year of practice, which is when you have to start thinking about fishing or cutting bait on the whole partnership track,” Guggenheim says. “And two things were happening: I was developing more and more of a following for the writing I was doing, and I was appreciating the law less and less. The bloom was really falling off that rose. So, I thought, ‘You know what? If I’m ever going to do this, now is the time.’”

Fittingly, his first official TV writing gig came on a series from another ex-lawyer: David E. Kelley’s legal drama “The Practice.” Other credits eventually included “Law & Order,” “Eli Stone” and “DC’s Legends of Tomorrow,” the latter of which he co-created. Then there’s his current slate: He’s the executive producer and showrunner of “Carnival Row,” a Victorian fantasy drama, which rolls out on Amazon on Aug. 30; and he co-created “Arrow,” which heads into its final season beginning Oct. 15 after an eight-year run that spawned a televisual universe for the CW. He’s also running for one of the WGA West Board of Directors seats in the union’s upcoming election as part of the slate opposing the current strategy in the standoff with Hollywood’s talent agencies.

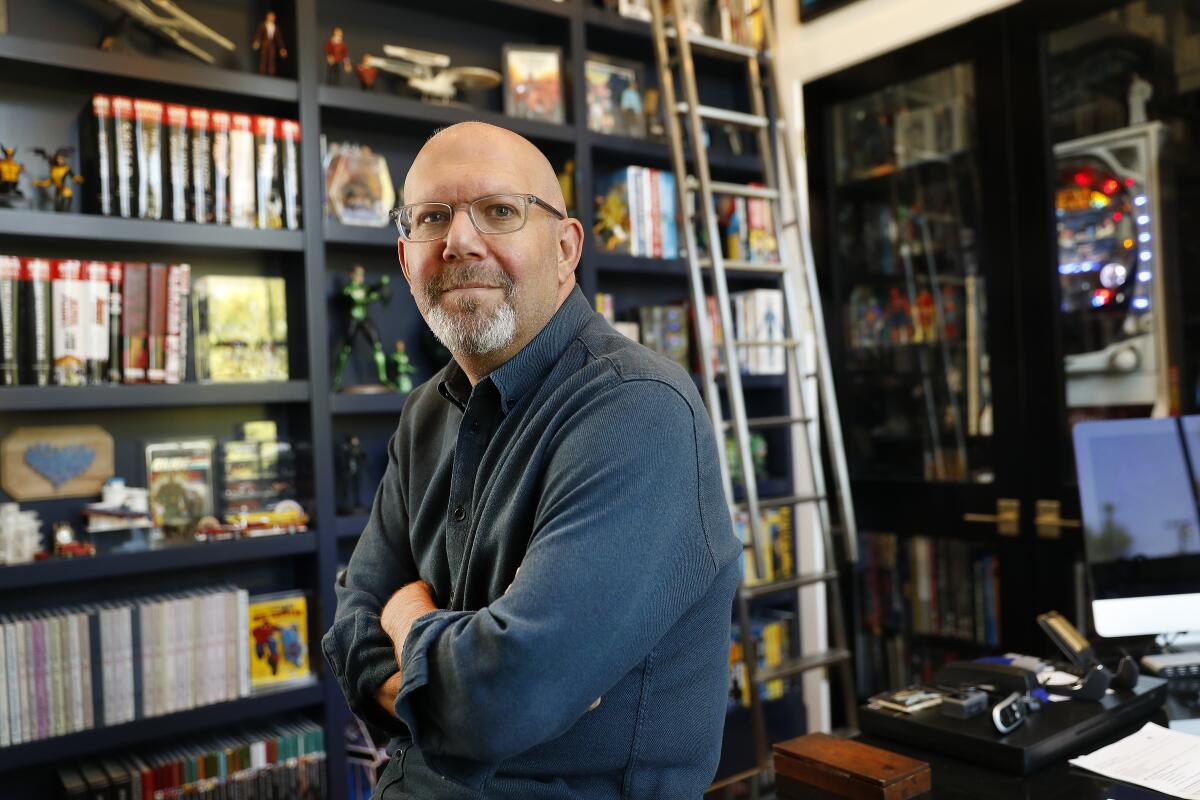

Amid framed Billy Joel album covers and superhero memorabilia at his home office in Encino, Guggenheim talked about how his background in law has informed his work, the challenge of breaking in as a young writer today, and the “Game of Thrones” shadow that now hangs over every new fantasy drama on TV.

WGA election fight: Shonda Rhimes, Ava DuVernay, Ryan Murphy and 300 others back dissident candidates in escalation of guild conflict over negotiations with agencies.

Why “the next ‘Game of Thrones’ ” label is “low-hanging fruit”

[T]he frustrating thing is, everyone’s comparing it to “Game of Thrones.” [But] anyone who sees the show I think instantly knows, for good or ill, that “Carnival Row” has as much in common with “Game of Thrones” as “Star Wars” does to “Star Trek.” It particularly vexes Travis Beacham because Travis wrote [the feature film spec script] “A Killing on Carnival Row” 17 years ago, long before there was even “Game of Thrones” the novel. So, it’s a bummer to be compared. I always said comparisons don’t serve us well. We’re our own thing. But people have to write reviews, people have to write articles, and it’s the low-hanging fruit. It’s funny. I think with every project I do, there’s some barrier to entry. With “Eli Stone,” the barrier to entry was this is a really weird show. Oh, and by the way, we’re premiere during the writers’ strike. No one was watching television. With “Arrow,” the barrier to entry was it’s a not well-known comic book character, who in the comics wears a Robin Hood hat and has a goatee and has a boxing glove arrow. With “Carnival Row,” clearly the barrier to entry there is this pall that “Game of Thrones” casts.

On saving “Arrow” from “jumping the shark”

I knew at the end of Season 6 [it was time to end “Arrow”], because I started to realize that I had done everything on the show that I wanted to do. I played all my cards. I realized that if the show was to have any sort of longevity beyond Season 6, some new voices and new blood had to come in. Beth [Schwartz, the show’s executive producer and showrunner,] and everyone injected the show with this new life, but the question was, “OK, how much longer do we want to do this?” I think it was something we all sort of collectively came to, but it was both collective and separate. It was kind of like this secret. Once we all started talking to each other, it’s like, “Oh yeah, you’ve been thinking that too? Oh yeah. You’ve been wondering that also?” It just came about very organically.

A couple years ago, I think it was the end of Season 4, I realized, “Oh, I know how to keep the show on the air for 20 years,” at least as far as some of the fans. Each episode would be self-contained. It would just be Oliver, Diggle and Felicity in the bunker, or solving a case of the week, with a billed supervillain of the week. ... The problem was, that was never the show any of us were interested in doing. I don’t think the actors were interested in doing a show where their characters didn’t evolve and change. I know I certainly wasn’t interested in writing a show with characters [who] didn’t evolve and change. Once you make the decision that the show is going to be constantly changing and not be the same thing, week in week out, year in year out, you are immediately building in an expiration date, because then you always have to do something new. At some point, you do run out of things that are new, and that’s when the show starts to lag and become ... that’s when you risk jumping the shark.

What “Carnival Row” has in common with “Star Trek”

One of my oldest memories was sitting on the floor in my bedroom and flipping through a Superman comic. And my mother came in and she’s like, “Oh, my God, you can read!” She thought she had a savant on her hands, and I’m like, “No, I’m just looking at the pictures.” I didn’t even know where I got the comic from. So yeah, genre’s always been a big part of life, but for the longest time it wasn’t a part of my writing. It wasn’t until I was in my fifth year in the business that I started writing comic books professionally. And it wasn’t until like the end of my seventh year in the business where I started merging the comic-book side of my career with television. “Eli Stone” was what I would call soft genre, but the first true genre show I worked on was “FlashForward,” and that was my seventh or eighth year in the business.

I like the ethos of genre stories. On the one hand, genre stories tend to be very black and white. There’s a protagonist, an antagonist, a good guy and a bad guy. On the other hand, one of the great things about genre is that you can really delve into issues in a way that’s more freeing than a non-genre show can do, and “Carnival Row’s” a perfect example of this. “Star Trek,” of which I’m a huge fan, is another great example. So I love the fact that this medium allows for both a lot of clarity and a lot of gray, but it’s hard to articulate why something speaks to you at such an early age.

How being a showrunner is like being a lawyer

I would say it informs me on a thematic level, and it also informs me on a practical level. Thematically, one of the things I think that’s great about law school is I can’t really think of any other academic endeavor where you’re not just learning facts, you’re learning how to think, and you’re learning how to think differently. And you’re mainly learning empathy. You’re learning how to view an issue from more than just your own perspective. And that is an absolute boon when it comes to writing, where you need to write from various different perspectives. From a practical standpoint, as a showrunner, it’s invaluable. Negotiating, problem-solving, thinking logistically, learning how to write fast. My secret weapon is I write very fast, and that’s because having to write a 50-page brief in a night is not unheard of when you’re a litigator. So you learn very quickly not to be precious about your writing. You also learn how to make decisions fast.

Two tricks for keeping one’s writing well-tuned

Before I go to bed at night, when my head hits the pillow, I will write a scene in my head. That’s usually going to be the first scene I write in the morning, so it’s kind of pre-written, which makes the day go by easier. The other thing I do is I will either read a script or watch a movie — pieces of it. I’ll watch a couple of minutes or read a couple pages of something that I call a “tuning fork,” something that is similar to what I’m working in that’s sort of just like a singer trying to hit the right note. “This is a good one.” Like, this is the note. This is the thing that is compatible with what I am writing” at that moment in time, and I find that to be very helpful.

Why it’s so much harder to break into the TV business today

For one thing, there’s far more writers. The competition is huge. For another thing, I was able to break in by virtue of my law career. My first two jobs were on law shows. That’s another genre headed to the West — that has gone away, for the most part. So it would be incredibly, incredibly challenging. Someone once said to me, “Breaking into television is a lot like breaking out of prison.” The methodology that one person uses doesn’t work for everybody else.

I’m a big believer in reading and writing. People ask, “Should I go to film school? Should I take a writing class?” and as someone who didn’t go to film school and didn’t take a writing class, I always impose my own experience on them. I always say, “I really feel like you learn by doing and you learn by seeing it done, and even a bad script will be educational.” The next thing I say is, “Develop and hone your craft.”

Unfortunately, I feel like nowadays in America we’ve replaced ambition with entitlement, and the thing that I see in a lot of young writers who ask me advice are, “I wrote the script. Why can’t I get an agent?” Well, write more than one script. Keep writing scripts. Very, very, very few people nail it the first time out. It really does take time to master the form, and it’s only when you master the form that you can start injecting some artistic expression into it. And that artistic expression needs to be unique. ... The town is filled with competent writers. Some competent writers will get work, but the vast majority won’t because writers are not hired for competency. They’re hired for their voice. It’s the one unique thing that you have to offer that no one else that you’re competing with can. So what I always tell young writers is, “Hone your craft. Work to find that script that says who you are as a writer. What makes your voice so unique that it has to be heard?” And that’s hard to do. It’s really, really hard to do. But when you can do it, you will never lack for work.

More to Read

The complete guide to home viewing

Get Screen Gab for everything about the TV shows and streaming movies everyone’s talking about.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.