How one family weathered the ‘terrifying’ spotlight of an HBO documentary

- Share via

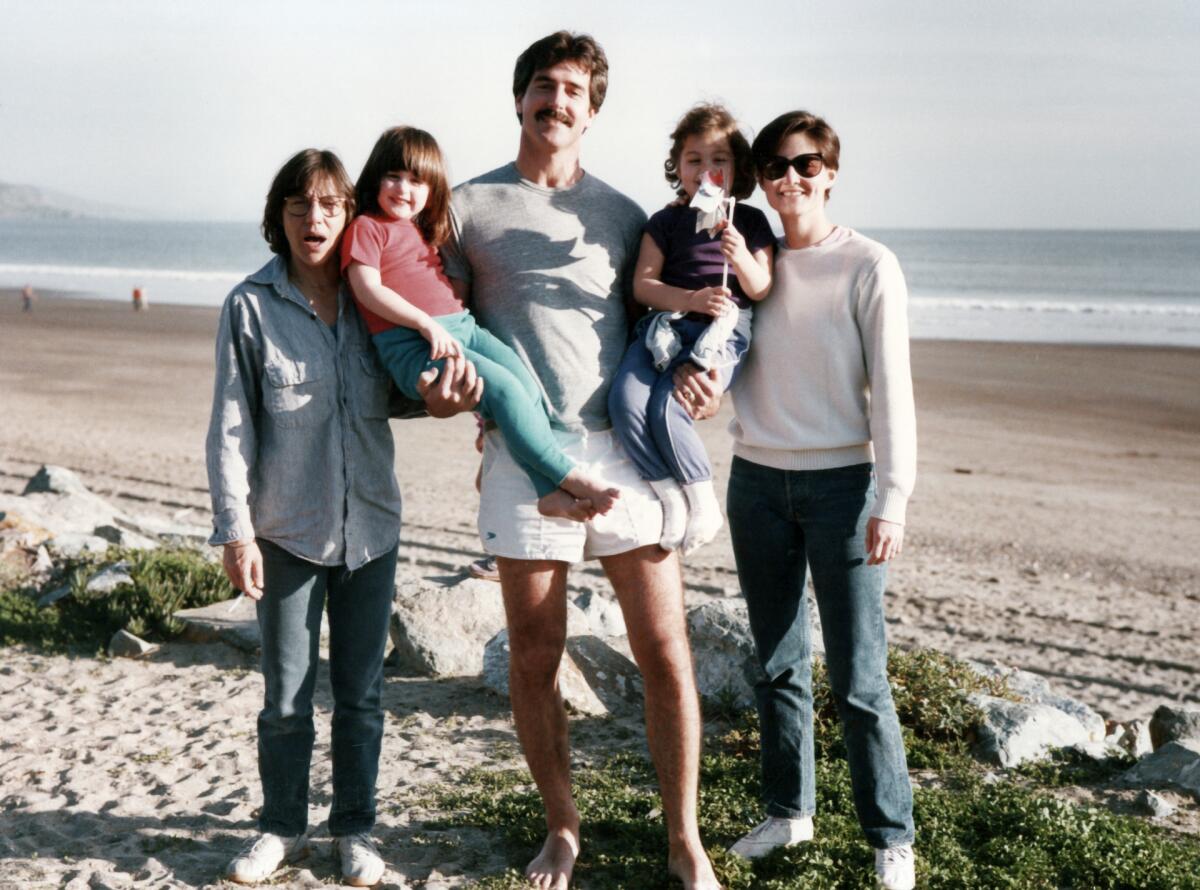

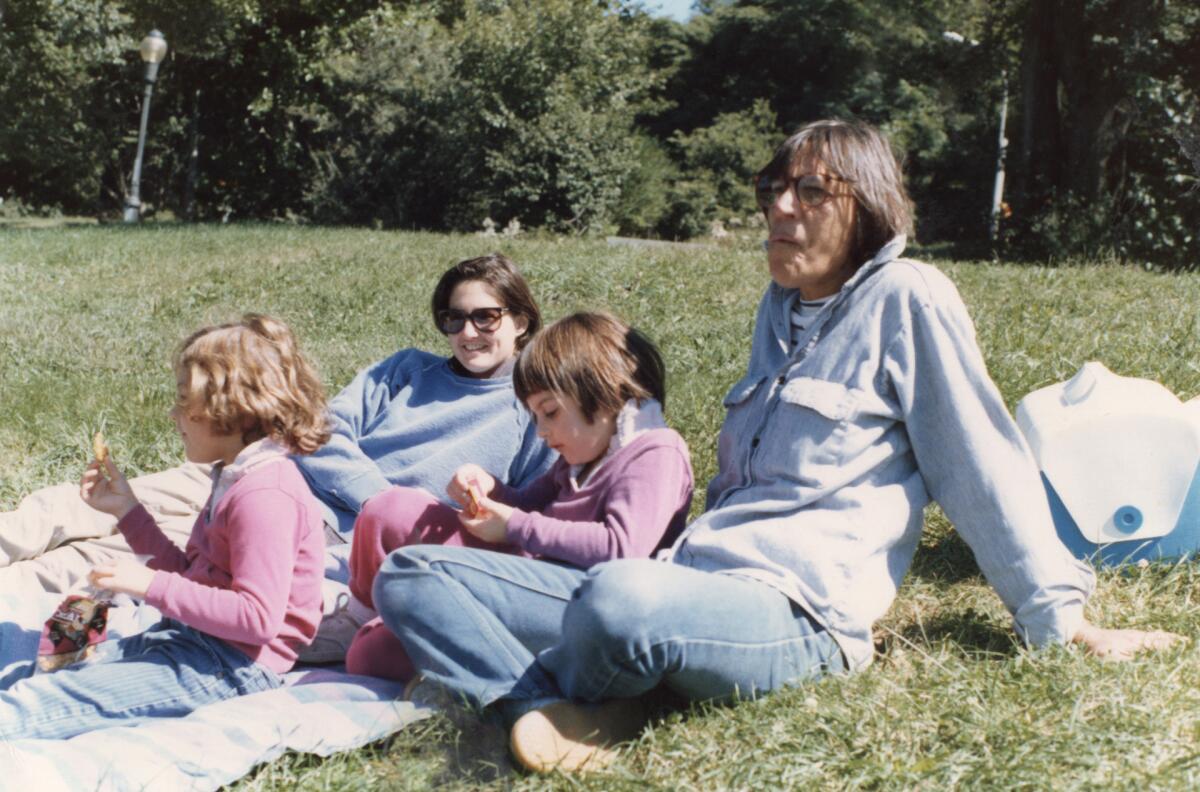

Robin Young and Sandy Russo wanted to start a family when it was virtually unheard of for same-sex parents to raise children together.

So they did: Using sperm donors, the women had two daughters, Cade and Ry Russo-Young, in 1980 and 1981. For several years, Russo and Young maintained a friendly relationship with Ry’s biological father, Tom Steel, a lawyer in San Francisco who’d fought for LGBTQ rights, even vacationing with Steel and his partner.

The complete guide to home viewing

Get Screen Gab for everything about the TV shows and streaming movies everyone’s talking about.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.

But, as chronicled in Ry Russo-Young’s three-part docuseries “Nuclear Family,” which concludes Sunday on HBO, the families had a falling-out: Steel shocked Russo and Young by suing for paternity and visitation rights in 1991, triggering a legal case that would drag on for years and cause intense emotional distress for all parties.

For Russo-Young, 39, who grew up making home movies with her family and eventually became a filmmaker, the story once seemed fit for a fictional feature — but when she tried writing the screenplay, she realized she still had questions about the case.

An HBO docuseries tries to unlock an urgent mystery.

Despite her reluctance to make a “navel-gazing, me-and-my-problems documentary,” Russo-Young decided nonfiction was the best way to answer those questions. She began to gather materials — home movies, legal documents, family photos, archival news footage — and interviewed family, friends and others involved in the lawsuit.

Russo-Young and her mothers, speaking by video conference from their respective homes in Los Angeles and New York City, told The Times about how the experience changed their views on the case, preparing for a particularly difficult interview in the final episode and the story’s future as a scripted series.

Ry, you go on something of a journey over the course of the series. Did you expect your perspective to change the way it did?

Ry Russo-Young: I didn’t expect my perspective to change. And I don’t think it has changed that much, actually. I think it was in some ways a grand exercise in empathy. I understand more deeply where everyone was coming from. My family is still my family. And I’ve always viewed my moms and my sister as my family, but I’m able to sit with empathy for Tom and be OK with that, as well as the feelings of betrayal and resentment and sadness.

I’m curious about how you approached having intense family conversations on camera and how you navigated the relationship between filmmaker and subject given your relationships?

Sandy Russo: We trusted Ry implicitly. We knew that she wasn’t going to throw zingers at us. She’s a director, so she knew how to put us at ease before the cameras started rolling. Sometimes we just forgot that the camera was there.

Robin Young: A lot of her childhood, college years and beyond, she just had a camera rolling. So we were pretty used to her sitting with a camera. Even though this was a little more intense.

Ry Russo-Young: Robin and Russo are incredibly natural and amazing storytellers. And I think that comes across. There’s a lack of self-consciousness. That’s why I felt that they would make such strong lead subjects and why the series begins with them and their love story. As people they’re funny, they’re hopeful, they’re dynamic and completely unapologetic about who they are. I couldn’t have asked for better subjects.

For the parents, was it triggering to have to relive any of this?

Robin Young: It was difficult to relive it for both of us. There would be nights after [doing interviews], where we would be up all night feeling like we were back in the case, re-litigating it in our minds. And then watching the film, the first time we saw it, it was a shock, and we had to step back and calm down.

Sandy Russo: Even before the filming, Ry was asking for materials. We had saved everything from the law case, every document, you name it; there were boxes and boxes of boxes. And then she asked us also to go through all our family photos from before she was even born. We were so deep into it. It all seemed so vivid. It came right back at us.

Robin Young: Which is what made it so hard.

What would you want people to understand about this period, which doesn’t seem so long ago, and the peril that you felt?

Robin Young: There is nothing scarier than being threatened with losing your children. It’s really that basic. And that threat was there. And it was real. And it was just terrifying.

Something I found upsetting was the way the case pitted a gay man against a lesbian couple at a time, during the AIDS crisis, when one hopes you would have been allies.

Sandy Russo: It was tragic. And we did feel like allies. In the beginning, when he was willing to donate sperm for us to enlarge our family, I think we were on the same side, and we were appreciative of his willingness to play this role. And then he just made horrible choices. We just had to defend against that.

Robin Young: There’s stuff in the film about how he didn’t want to be erased, but then it’s just like, no — he self-erased, in a sense, when he ruined the relationship. It was tragic that he was a gay man who would make these arguments in court, and it was tragic on a super-personal level as well.

For the moms, did your point of view change or evolve over the process of making and watching the series?

Sandy Russo: Because of those conversations, we grew much closer, if that was possible — understanding more clearly what the kids went through and Ry’s complicated battle, between the two poles that were pulling at her, the anger and disappointment and remembering these warm moments with him. He was wonderful and Ry loved him. But he didn’t help himself in a way that allowed this relationship to continue.

Robin Young: I think that we still hate him for what he did to our kids. He tortured them for years. It went on for years and at any time, he could have made the decision to stop, and he just didn’t. He kept going. So that hasn’t changed.

But what has changed is our seeing Ry evolve on the subject and being able to hold all of those emotions at once in her heart — the pain and the love, the betrayal, all of it. It has given us huge respect for Ry and made us appreciate her more. And she’s able to express all of that in the film, and the depth of our love and the complication of it all is just amazing to us.

Ry, in the final episode, we see you ask your moms some difficult questions about Tom and the way they handled the dispute with him, and it’s very intense. Tell me about the decision to do that on camera and what inspired it.

Ry Russo-Young: I had shot and assembled most of the series. We had a whole cut, but Part 3 wasn’t quite there. And Dan Cogan, my producer, was like, “I think you have to go back to your moms and ask them some of these tough questions.”

It was a really terrifying, nerve-racking experience, having to figure out what those questions were and then prepare my moms — not give them the questions in advance, but let them know that this is going to be a really difficult discussion and that I’m asking these questions not because I want to hurt them or that I think they did anything wrong, but just for my own edification. And I remember saying, “I am going to ask these questions because I think we are a strong enough family that we can get through this.” But it was really difficult for all of us.

You reveal at the end of Episode 2 that Tom, who died in 1998, had been diagnosed with AIDS. Do you think Tom’s awareness of his mortality weighed into the decisions he made?

Ry Russo-Young: I think his diagnosis absolutely affected everything and potentially was influential in his decision to sue. He had limited time. And he felt like he needed a relationship with me right now. He was not willing to let things play out. There was this sense of explosive urgency.

Ry, how did making this documentary affect you as someone who is now a parent yourself?

Ry Russo-Young: There’s certainly a cycle of life to all of this. How your parents were raised affects how they parent you, and then how you’re raised affects how you parent. And that emotional passing-on outlives you, which is really existential and incredible.

There were so many things I learned about being a parent. One of the things I think the series made me really appreciate was just how fast it is. It’s such a cliche, but I look back at that footage, I see me as a 5-year-old and I remember it. I remember the lawsuit, I remember being a teenager with a Hi8 camera. And now I’m giving my child a Polaroid camera. It just blows my mind.

Are you still still thinking about a scripted version of this story?

Ry Russo-Young: Yes, a series is in the works. To your point about being a parent, I think in the fiction I can really dive deeper into the parental perspectives. Both of my moms and also Tom’s perspective and [his partner] Milton’s. It’s this idea of empathy one step further, so you can actually live with the characters.

More to Read

The complete guide to home viewing

Get Screen Gab for everything about the TV shows and streaming movies everyone’s talking about.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.