Mackenzie Phillips and Rob Reiner say Norman Lear was like family, offering ‘open arms’ and ‘love’

- Share via

Mackenzie Phillips was just 16 when she met with Norman Lear to talk about playing rebellious teenager Julie Cooper in his sitcom “One Day at a Time.” She was by then an established actor, known for roles in “American Graffiti” and the TV movie “Go Ask Alice,” and had had to grow up fast in a famously dysfunctional showbiz family.

Still, she was intimidated.

“I remember thinking, ‘Oh my gosh, I am going to go sit down with the Norman Lear. “He said, ‘Mackenzie, close your eyes.’ And I felt completely safe with him, so I closed my eyes. And he said, ‘Your face in repose tells a story that people need to hear.’ And I’ve carried that sentence with me for, what, 50 years? The man is unforgettable,” recalled Phillips, speaking by phone this week, following Lear’s death at 101.

The hugely influential TV producer helped transform American culture through sitcoms that blended laughter with serious topical issues including “One Day at a Time,” which centered on a divorced mother and her two teenage daughters.

When she heard the news of his death Wednesday morning, “I felt like someone shot an arrow through my heart,” said Phillips, who grieved for Lear’s family but also “the whole country. We lost a very important voice who started talking about social justice long before it was even a term.”

“He obviously was way before his time,” she continued. “I think he had a deep understanding of marginalized communities and wanted to shed a light on underrepresented portions of the population.”

“One Day at a Time,” which aired on CBS from 1975 to 1984 and was a Top 20 hit for most of its run, starred Bonnie Franklin as Ann Romano, a woman raising two adolescent girls largely on her own while also trying to compete in the job market after years as a homemaker. Julie, Phillips’ brash character, and the quieter Barbara (played by Valerie Bertinelli) were loosely based on Lear’s own daughters. Phillips saw Lear as a quasi-paternal figure, and said she and Bertinelli even called Lear “Uncle Norman.” Though less overly political than “Maude,” it captured an experience that was relatable to many women at a time when divorce rates were skyrocketing and second-wave feminism was changing the American workplace.

Norman Lear showcased actors and writers of color in his work, and the reboot of ‘One Day at a Time,’ which he executive produced, was no exception. It changed the way this writer engaged with TV, and his life.

“Norman fought for what he felt was right, and he wanted to represent what a single mother raising two children alone looked like,” Phillips said. “[Ann] was dating and having sex and her kids were growing into young women and had questions about birth control and losing their virginity and all these things that were absolutely explosive in the ‘70s. People just weren’t talking about this stuff.”

Phillips recalled that as color-coded script revisions came in each week, she always looked forward to the yellow pages labeled “Lear polish” in the upper-right hand corner to indicate changes he had personally made to the script. “Every time I got a ‘Lear polish’ script in my hand, I was like, ‘Oh my God,‘” said Phillips, who still has her scripts in storage.

As “One Day at a Time” reached the height of its popularity, Phillips struggled behind the scenes with drug addiction and was fired from the show — twice. Phillips said her relationship with Lear was strained for a brief period of time after her departure, though “it was probably more awkward for me because I felt shame and regret and sadness.”

“But Norman just always had open arms and love [for me], with a little bit of trepidation,” she said. “Like, ‘I love her so much. Do I take a chance of loving her that much again? Or is my heart going to get broken again?’ As our relationship rekindled and grew, those things fell away.”

Despite what happened on “One Day at a Time,” Lear was “always in my corner,” Phillips said. “Our paths would cross here and there over the years and he would always grab my face and say, ‘Oh, there’s that punim” — the Yiddish word for “face.”

Phillips, who now works at a drug treatment center in Los Angeles, also starred as Pam, a therapist, in a rebooted version of “One Day at a Time” that aired on Netflix (and later moved to Pop). Lear was closely involved in the new series, which featured a Cuban American family in Echo Park. “It was just incredible and full circle to be able to sit on a set with him again on the stage with him again,” she said. “He was just always so witty, charming and acerbic at times, but just delightful. He was a man full of grit and he was laser-focused on what was important to him.”

For Rob Reiner, who played Archie Bunker’s liberal son-in-law Michael “Meathead” Stivic in “All in the Family,” the news of Lear’s death, though not unexpected, was devastating.

“I knew he wasn’t going to be around much longer but it still hurts. He’s like a second father to me and I couldn’t be closer to a male role model in my life,” said the filmmaker by phone Thursday, while en route to tape a special for Dick Van Dyke, who turns 98 this month and, like Lear, was a close friend of his father, Carl Reiner, who died in 2020 at 98.

“These people that were big in my father’s life and I spent a lot of time with — they’re all getting older and going,” said Reiner, who has known Lear since childhood and says he was one of the first people to think he had a knack for performing.

“Norman tells a story that I was playing jacks with his daughter Ellen, who is my age, and I was apparently explaining how jacks worked,” he said. “I was doing it in a funny way and he was laughing. He told my father, ‘Your kid is really funny.’ My dad said, ‘What are you talking about? That kid? He’s surly.’ I think I was 8. He was the first guy that recognized I had any talent — or at least talent in explaining how to play jacks.”

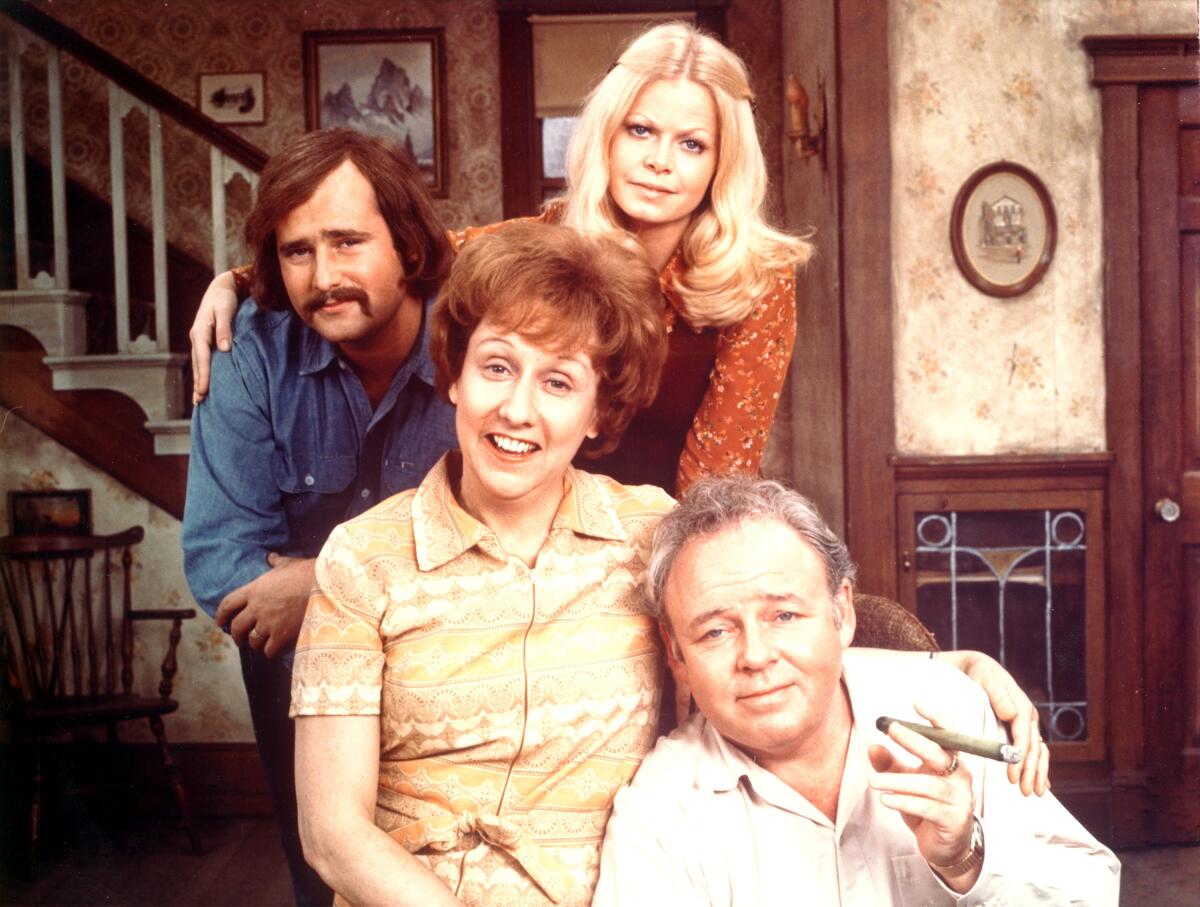

Some years later, Lear would cast Reiner in “All in the Family,” which would become his most celebrated sitcom — winning 22 Emmy Awards and reigning as the No. 1 show in the Nielsen ratings for five straight years.

Well before streaming, Tivo — or even VCRs — the CBS series had a unique power to steer the national conversation. During the waning days of Vietnam and the rancor of the Watergate era, the conflict between Meathead, an educated, politically progressive hippie, and Archie, a working-class bigot, resonated with millions of Americans. “You had to watch it when it was on and 45 million people are having the shared experience. And the next day, you see people and you talk about it. ‘Did you see what they said?’ And you’d have a conversation. Now everybody’s kind of stuck in their own little silos,” Reiner said. “I think, in a way, he brought people together. Half the people liked Archie, and half the people like my character.”

Norman Lear’s cantankerous, bigoted creation ignited dialogue, not a culture war. We could use him now.

Reiner remembered how Lear fought back when the network threatened to pull a controversial episode of “All in the Family” in Season 1 before the sitcom became a breakout hit.

“Norman said, ‘Fine, you don’t have to air it but call me in the Fiji Islands because I’m quitting,’” Reiner recalled. “There’s a Yiddish word that I used for him, it’s kochleffel, which is a ladle that stirs the pot. That’s what he liked to do. He was fearless. Somebody asked me once if it was tough for him to deal with the censors and the network executives and I said, ‘This is a guy who flew 52 bombing missions over Nazi Germany during the Second World War. I don’t think he had a problem with network executives. They didn’t scare him that much. He stuck to his guns and did what he thought was right and God love him for it because he created some great, long-lasting, groundbreaking television.”

Reiner said Lear provided invaluable support as he moved from acting into directing, a transition that would lead to acclaimed films including “The Princess Bride” and “When Harry Met Sally.” “He financed the first four films I made. If it wasn’t for him, I would never have gotten to make ‘Spinal Tap’ because he had faith I could do it,” said Reiner.

When Columbia Pictures almost canceled the filmmaker’s third feature, “Stand by Me,” days before production was to begin, Lear stepped in to finance the project with his own money. The film went on to become a critical and commercial hit — and is widely regarded as a modern classic.

But for Reiner, Lear’s biggest influence was his political advocacy. “When he started People for the American Way, I saw you can use your celebrity to try to affect change, so that got me into doing that kind of thing,” said Reiner, who has been active in liberal politics for decades.

In films like “A Few Good Men” and “Ghosts of Mississippi,” Reiner said he tried to follow the example Lear set by telling stories that were both entertaining and socially relevant. “That’s a tough thing to do. He did it with not just ‘All in the Family’ but ‘Maude’ and ‘The Jeffersons’ and ‘Good Times.’”

Reiner, who is producing a documentary about Christian Nationalism called “God and Country,” said he remains committed to carrying on Lear’s political and creative legacy.

“Here we are, less than 80 years after he defeated fascism and we see fascism creeping back into society,” Reiner said. “I had many conversations with him in the last year or so. He said, ‘I can’t believe this country’s become a country I don’t recognize anymore.’ We have to honor him by continuing to fight. Otherwise, what is he doing, you know, risking his life flying 52 missions over Nazi Germany?”

Reiner was able to say a few words to Lear over the phone shortly before he died, when he was still awake but unable to talk, and said that he’d seen him regularly over the last few months. “I’d always tell him I love him,” Reiner said. “‘Love you more,’ he’d say.”

More to Read

The complete guide to home viewing

Get Screen Gab for everything about the TV shows and streaming movies everyone’s talking about.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.