Robert Schuller: A patron of modernist architecture

- Share via

He began with a drive-in church designed by Richard Neutra located just three miles from Disneyland. Over time he added a telegenic cathedral by Philip Johnson and a shimmering, cylindrical “hospitality center,” with an auditorium and cafe, by Richard Meier.

Robert H. Schuller, the evangelist who died Thursday at age 88, doesn’t just belong on any shortlist of Southern California’s major architectural patrons. His long infatuation with high-profile architects -- “There’s a place for monuments,” he told the Times in 1980, adding that “if the monument can be an instrument, you’ve got a winner” -- produced something quite rare: a collection of buildings that has something important to say about the evolution of both modern architecture and Orange County.

In fact, when the Roman Catholic Diocese of Orange purchased the campus in 2011 for $57.5 million, changing the name of Johnson’s Crystal Cathedral to Christ Cathedral, it was not merely buying a foothold in a county that is home to more than a million Catholics.

It also acquired a property that, thanks to Schuller’s patronage, is much more of a place – an architectural ensemble – than most people realize. Perhaps only on Bunker Hill in downtown Los Angeles, where buildings by Isozaki, Gehry, Becket, Prix and Moneo line up side by side, can Southern Californians get such an efficient education in the architecture of the last half-century.

Before he hired Neutra in 1959, Schuller and his wife, Arvella, conducted services from a drive-in movie theater in Orange. He preached while standing on the roof of the concession stand.

When it was time to expand, on a 10-acre parcel in nearby Garden Grove, Schuller asked the architect, then 67 and nearing the end of his career, to produce a new building that would retain key elements of that drive-in ministry.

Neutra designed a long, low, flat-roofed church with huge movable glass walls that allowed Schuller to be seen and heard by those inside as well as in the parking lot, sitting in what the minister called the “pews from Detroit.” It is far from Neutra’s best work, though the experience was significant for both men. Schuller once listed the architect, along with John Calvin, Norman Vincent Peale and Billy Graham, as a key influence on his intellectual development.

Neutra’s son Dion, also an architect, added a 15-story “Tower of Hope” in 1967, a vertical marker that in the words of architectural historian Thomas Hines “was more prominent than anything on the Orange County landscape except the nearby ‘Matterhorn’ at Disneyland.”

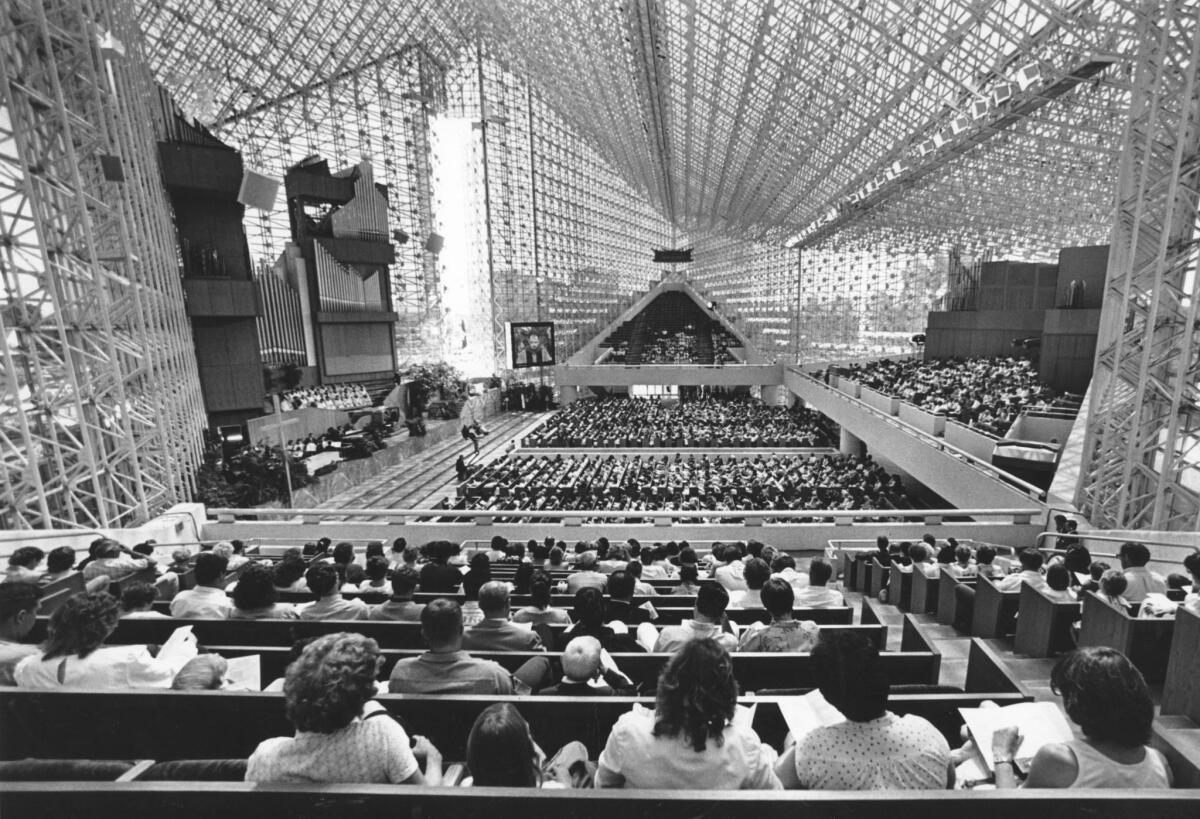

A little more than a decade later Schuller wanted to expand again. He turned to Johnson and his design partner John Burgee, who at a cost of just under $20 million produced a huge room under a faceted glass ceiling, 207 feet wide, 415 feet long and 128 feet tall.

Finished in 1980, it was a cathedral designed, as Neutra’s building had been, with an eye toward multiple audiences -- including, this time around, television viewers sitting at home. The glass backdrop and giant interior space of Johnson’s building suggested a perfectly up-to-date tableau of modern Orange County beamed, as the Reagan years dawned, to a national audience.

Even on TV you could tell how sunny it was outside by watching the light play over Schuller’s face. This was architecture that sold the appeal of Southern California on television just as the Rose Parade did every New Year’s Day.

There was more than a touch of futurism in those televised images of Johnson’s glittering and transparent monument. As architect Charles Moore put it in his 1984 book on Southern California, the first guide to take Orange County architecture seriously, Schuller “wanted a church embedded in nature, a bit recollective of the Garden of Eden. What he got is a church that might seem rather more at home in outer space.”

But Johnson, always a kind of architectural time-traveler, was looking to historical precedents too. At an event held for architects and designers at the cathedral soon after it was completed, Johnson, then 75, quoted the German modernist Erich Mendelsohn, whose most important work came in the 1920s: “Architects will be remembered by their one-room buildings.”

Johnson added that he was proud to have added this vast single room to Orange County, telling the group, “I hope to be remembered by this building.”

As Neutra’s office had done, Johnson waited a few years before adding a spire, giving Schuller, who spent money at the kind of clip that thrills architects and keeps church accountants up at night, time to figure out how to pay for it. Johnson’s campanile, which cost $5.5 million and rises 236 feet, was completed in 1990.

Meier’s addition to this collection of churches, spires and parking lots came in 2003. The cylindrical four-story building, wrapped in embossed stainless-steel panels and officially called the International Center for Possibility Thinking, was a shinier version of Meier’s pavilions at the Getty Center, completed six years before.

Was the Meier building the equivalent of a McMansion commissioned by a family living beyond its means? Perhaps. Schuller’s church declared bankruptcy in 2010. The campus was acquired soon after by the Roman Catholic Diocese, which has hired the Los Angeles firms Rios Clementi Hale and Johnson Fain to update it.

But Meier’s design also managed -- against long odds, given the differences in style and philosophy among the three architects -- to bring all of Schuller’s landmarks into a cohesive whole. And it did so by banishing the car, which had been so central to Schuller’s vision of an expansive, even sprawling ministry, in favor of the pedestrian, and trading the suburban design cues of Neutra and Johnson for a more civic, even urban idea of collective space.

The three buildings now consider one another across a carefully proportioned courtyard that suggests, in ways both hackneyed and effective, an Italian piazza. The Neutra and Johnson designs, meant to serve to an atomized region connected by freeways, suddenly have something to say about community.

The energy of the architecture such as Eero Saarinen, is no longer directly entirely outward, to parking lots and television sets, but has turned inward. The courtyard is a place not for the newcomers Schuller once preached to, unwilling to leave the comfort of their cars, but for people, and buildings, that have been here awhile.

More to Read

The biggest entertainment stories

Get our big stories about Hollywood, film, television, music, arts, culture and more right in your inbox as soon as they publish.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.