Will Salvation Mountain find its savior? The quest to save the desert folk-art landmark

- Share via

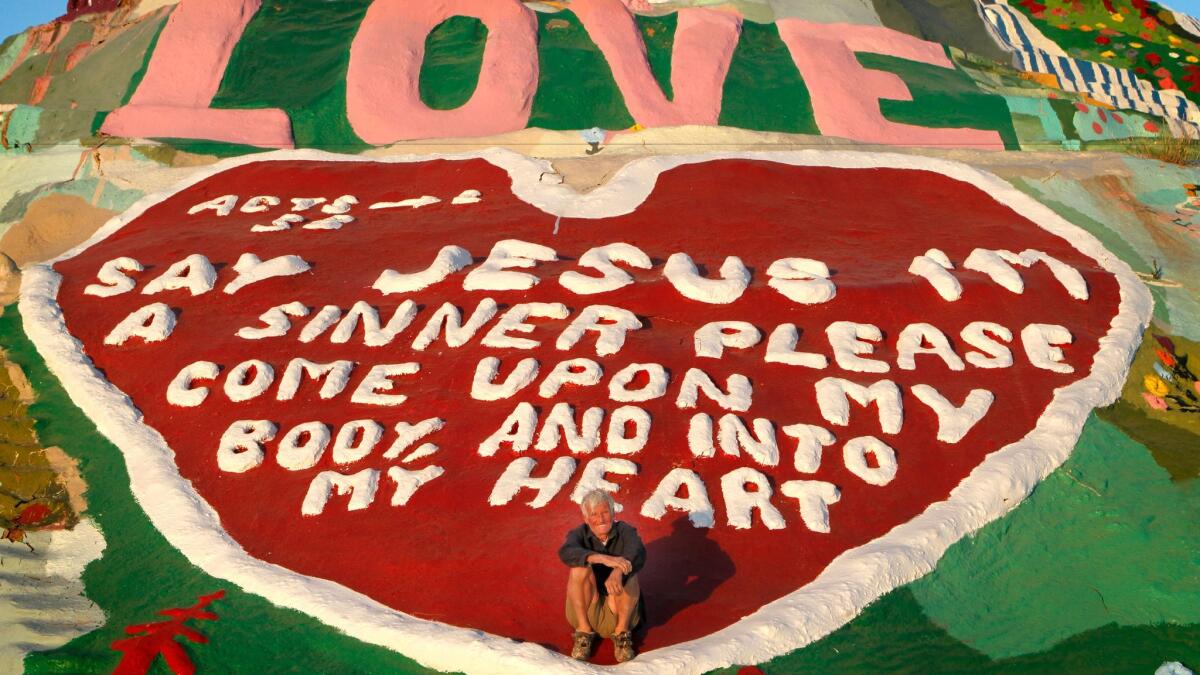

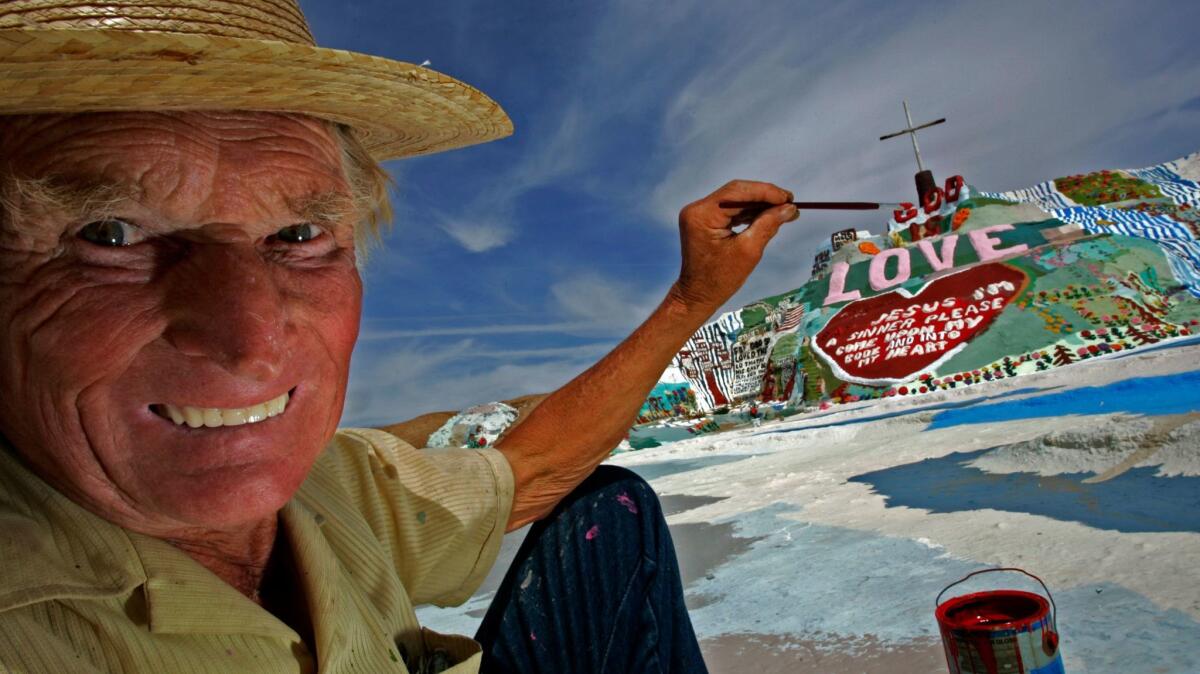

Reporting from Slab City, Calif. — People call it a mountain, but it’s just 150 feet across and five stories tall, jutting skyward like a candy-colored, Jesus-inspired hallucination brought to life on the subdued pastel palette of the desert. Created in a sustained fever dream by the self-taught artist Leonard Knight over nearly three decades, Salvation Mountain rose as a monument to individual fortitude and artistic inspiration, growing in significance and fame even after Knight died in 2014 at age 82.

It’s a magnet not only for fans of outsider art but also for authorities such as Jo Farb Hernández, professor at San Jose State, head of the university’s art gallery and director of a nonprofit called Spaces that advocates for large-scale art environments. Hernández called Salvation Mountain one of the most important public artworks in the country. “It’s a phenomenal site,” she said. “People who have been there have really been changed by that experience.”

Now, however, Salvation Mountain finds itself in a bit of limbo. Knight built his monument without permission, on California state land east of the Salton Sea, where it’s vulnerable to the elements as well as an ever-increasing number of tourists, art pilgrims and curiosity seekers.

“In the last year-and-a-half we’ve about doubled our visitorship,” says Dan Westfall, the president of Salvation Mountain Inc., the nonprofit that has taken charge of maintaining and protecting the mountain. “We’re getting close to 2,000 people a week from all over the world.”

Knight constructed Salvation Mountain by covering hay bales with stucco and then painting the surface. This construction is fragile by nature — fragility exacerbated by the extreme climate and the fact that visitors are free to roam and climb. Tour buses have discovered Salvation Mountain, arriving regularly from San Diego and Los Angeles.

“The heels on your shoes can unintentionally rip a gash in the surface of the paint, and once that happens, rain and sun will split those cracks even further and create even more damage,” Hernández said.

Further complicating matters: The property is owned by the state, but the artwork is preserved and protected solely through the efforts of dedicated volunteers.

“Coping with visitors can sometimes be a challenge,” Westfall said. “But we’re getting a cadre of people now that know the mountain and love the place and continue to work on it and maintain it.”

Knight, a Korean War veteran and nomadic laborer and mechanic, arrived in the community known as Slab City in 1984 on a quixotic quest. He had spent the preceding 10 years crafting a 200-foot-tall patchwork hot-air balloon emblazoned with the giant inscription, “God is Love!”

A fan of westerns, Knight was drawn to the openness and freedom offered by the California desert and saw this fringe-y, off-the-grid community as the ideal lift-off point for a Jesus-fueled balloon voyage. The balloon shredded apart during the attempted launch, but Knight stayed and began a new project that would become his life’s work and his legacy.

Using stucco and found materials, Knight constructed Salvation Mountain as a monument to his religious faith. He lived alone in the back of his truck, kept company only by a collection of cats. He had no running water or electricity. Neighbors and visitors brought him provisions, building supplies and paint — lots and lots of paint, often a few mismatched gallons at a time. Toward the end of his life, Knight estimated that he had used half a million gallons of paint in creating Salvation Mountain.

The artist worked without a plan, following his inspiration at any given moment and letting God guide his brushstrokes. Over time the mountain became a tapestry flowing with brightly painted biblical verses crafted out of window putty or stucco. Blue rivers cascaded down vivid white bluffs to create the impression of waterfalls. Purple and yellow birds took flight above stucco flowers that Knight created by forming a lump of mud and smashing his fist into it. Although Knight didn’t see himself as an artist, he wanted his mountain to be “as pretty as Jesus.” Most important, he wanted it to be a manifestation of the joy and love that he felt so deeply in his heart.

“Knight saw the mountain as a way to present his vision of God’s beauty and wonder to a broad audience,” said Mark Sloan, curator of the Halsey Institute of Contemporary Art in Charleston, S.C., who has written about folk art. “Knight was trying to get people to go back to a time when they had the capacity to be awestruck and instill in them a sense of wonder.”

Although the state of California has a contentious history with Salvation Mountain, attempting to bulldoze it in 1994 to make way for a campsite, the relationship has improved dramatically. Jim Porter of the State Lands Commission, which holds title to Salvation Mountain, is optimistic about a deal to keep Salvation Mountain protected. Porter said the best custodian for the site is Westfall’s organization, which is positioning itself to purchase Salvation Mountain from the state.

“They have a vested interest in the property since they knew Knight, were followers of his and want to maintain his legacy,” Porter said.

Protecting Salvation Mountain would be a boon to Imperial County, Westfall said.

“People are coming to the mountain for totally positive reasons and going away feeling great,” he said. “It’s a national treasure in a county that doesn’t have a whole lot in the way of positive tourism.”

Three years after Knight’s death, his art and its message of universal love is still connecting with people in unforeseen and unpredictable ways, he said.

“We find people often leave something of themselves here — student cards, credit cards, driver’s licenses, anything that has their name on it,” Westfall said. “They feel connected to the mountain and they want to stay connected.”

SIGN UP for the free Essential Arts & Culture newsletter »

Follow The Times’ arts team @culturemonster.

ALSO

Times art critic Christopher Knight’s latest reviews

‘Pope of Broadway’ mural featuring actor Anthony Quinn fully restored

In Theaster Gates’ latest work, poignant power from the remnants of our history

A Japanese art collective’s Tijuana treehouse peeks across Trump’s border

More to Read

The biggest entertainment stories

Get our big stories about Hollywood, film, television, music, arts, culture and more right in your inbox as soon as they publish.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.