Review: Is that a laugh? A cry? In Ben Jackel’s sculpture, messages molded by deft hands

- Share via

In Ben Jackel’s large exhibition of recent work at L.A. Louver, one sculpture starts with a bearded battle ax — the kind used in ancient Norse warfare, on a medieval executioner’s block or now in conventional woodworking. Then, he doubled the form.

Two monumental hooked blades, each 5 feet high and 5 feet wide, stand upright side by side. Jackel carved them from wood. Their irregular surfaces have been rubbed with a dark graphite that emphasizes the brusque chop-marks on the rough-hewn Douglas fir, now glinting in the light.

The formal repetition of the two establishes a conceptual dichotomy, while the scale asserts its gravity. The weapon embodies the type of hand tool with which the sculpture was made, enlarging it to epic size. The ax stands as an implement of death and an instrument of art — of destruction and creation in equal measure.

That it’s sculpture declares where the artist’s unequivocal commitments lie. Jackel’s is a political art of a subtle and sophisticated sort.

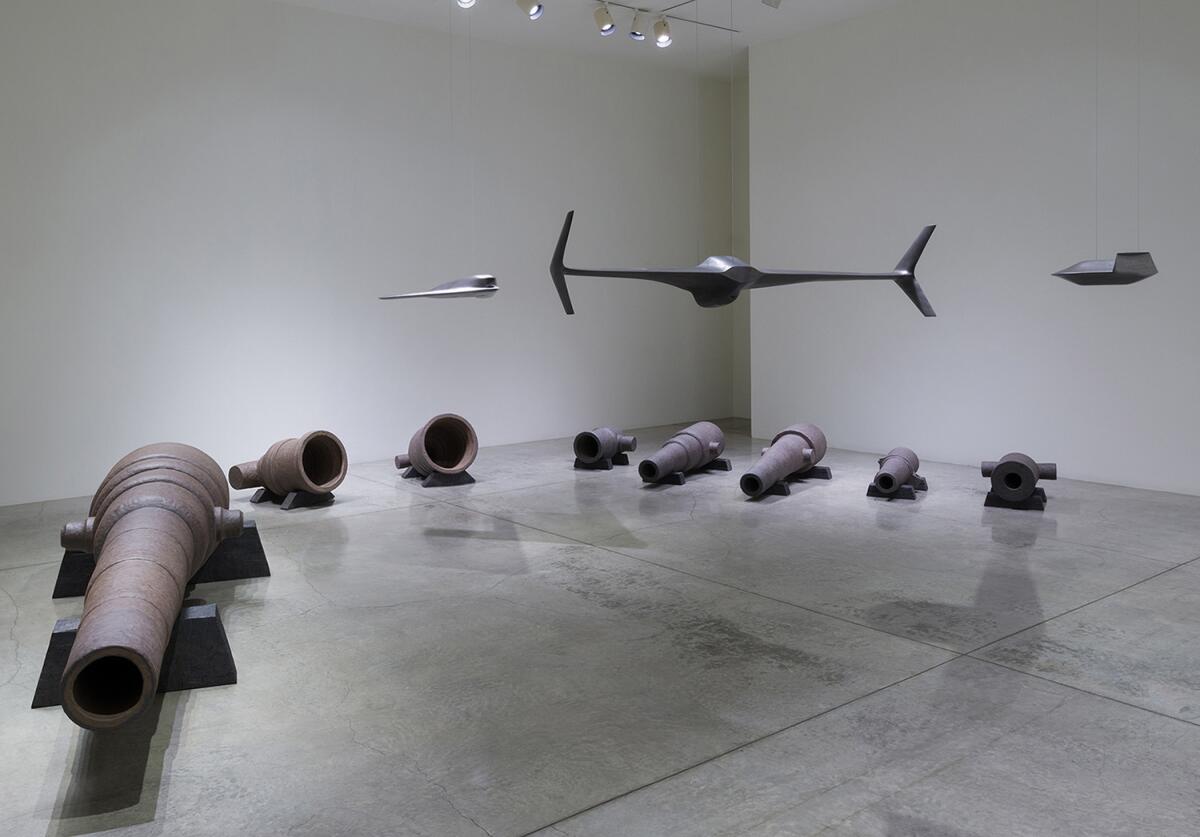

Except for three sleek, suspended sculptures of stealth bombers, the show’s other 22 works are stoneware — dense, opaque and visually heavy. Because fired clay is also breakable, hefty sculptures of cannons, armor and a foothold bear trap are as materially contradictory as the ax head. They’re fearsome yet fragile.

They are also exquisitely rendered, perhaps none more than a helmet with night-vision goggles.

It’s rubbed with beeswax, as are many of the other dusky stoneware pieces, which yields a soft, light-diffusing, visually tactile surface. Together with a full-size gas mask, as well as three medieval helmets with thin slits for the eyes, through which almost nothing could be seen by a warrior encased inside, the sculptures are concise, carefully crafted essays on militaristic blindness.

Eight bulky models for muzzle-loaded cannons include the famous 100-ton guns that the British mounted in the 1880s at the Rock of Gibraltar at the Mediterranean gate. (Britain’s 100-ton gun was more than 32 feet long; Jackel’s version is about 1/3 scale.) The gigantic weapons were manufactured in response to the complex geopolitics of the day — notably, the opening of the Suez Canal, which reconfigured relations between Europe and the Middle East.

Sound familiar? Their significance for today is hard to miss. Nearby, stoneware models of a lifeboat, Ernest Hemingway’s fishing vessel and Lewis & Clark’s Corps of Discovery, laden with black powder to safeguard the boats’ exploratory movements, climb a white wall. All seem destined to sink.

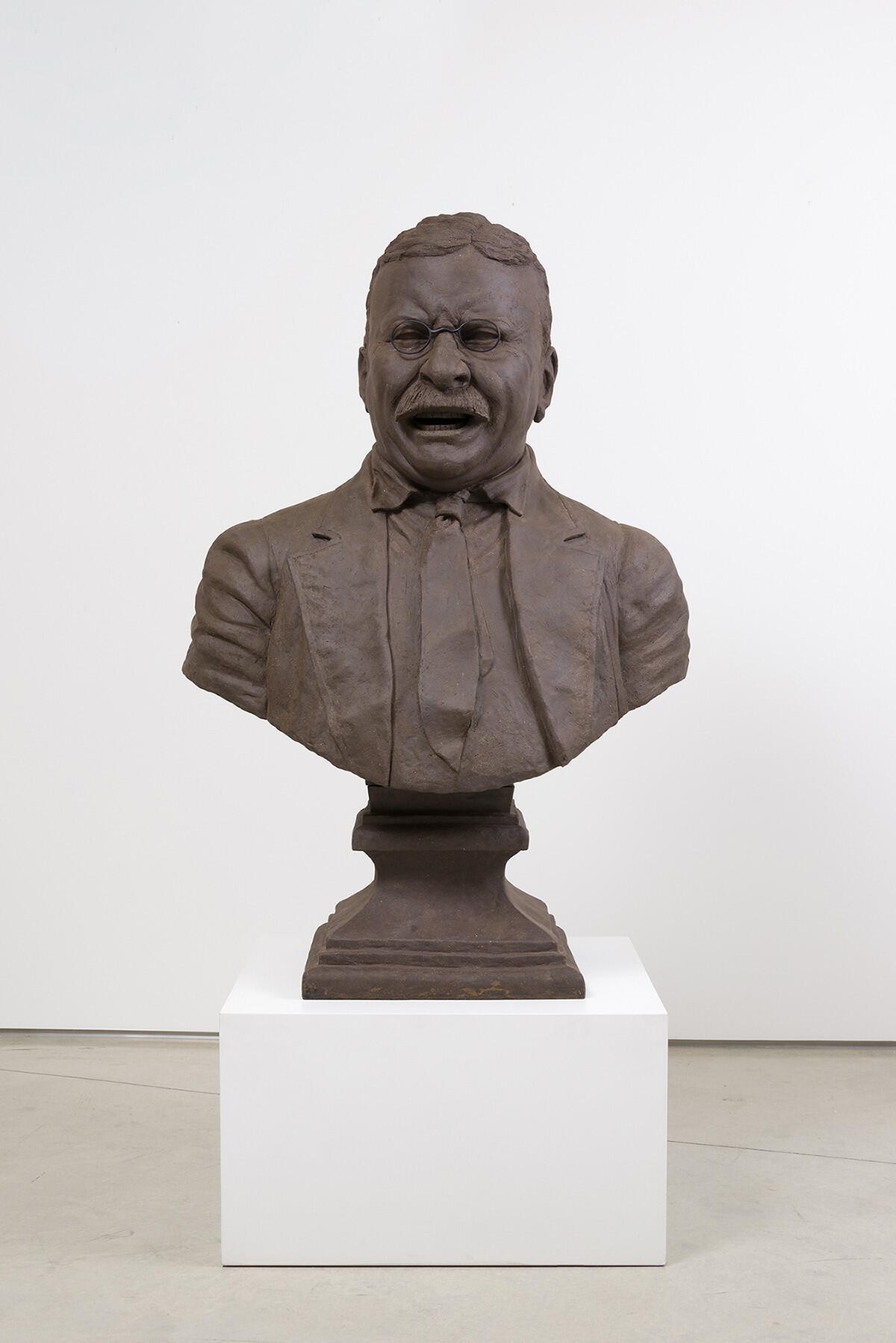

The show’s tour de force is an oversize bust of Teddy Roosevelt, apparently adapted from a famous laughing photograph of the equally larger-than-life president. In Jackel’s deft hands, his toothy demeanor has been altered to be more conflicted — laughing, shrieking, crying or perhaps all three at once.

Think Francis Bacon’s paintings of screaming popes grafted onto the archetypal ex-Republican, whose byword was “Bully!” and whose perplexing politics incorporated both progressive and nationalist values. The astonishing bust is an authoritative image of executive chaos — and clearly less about the past than the present.

The imposing bust is preparation for the forbidding, 7-foot monolith that stands in splendid isolation in the center of a small adjacent gallery. Modeled on an ugly black-glass skyscraper on Manhattan’s Fifth Avenue, the one that the current president calls home and where he recently delivered shocking comments on white supremacists, it is titled “Dark Tower” — like the magnum opus of horror master

Not subtle, but apt.

L.A. Louver, 45 N. Venice Blvd., Venice; through Sept. 1; closed Sundays and Mondays. (310) 822-4955, www.lalouver.com

Twitter: @KnightLAT

The biggest entertainment stories

Get our big stories about Hollywood, film, television, music, arts, culture and more right in your inbox as soon as they publish.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.