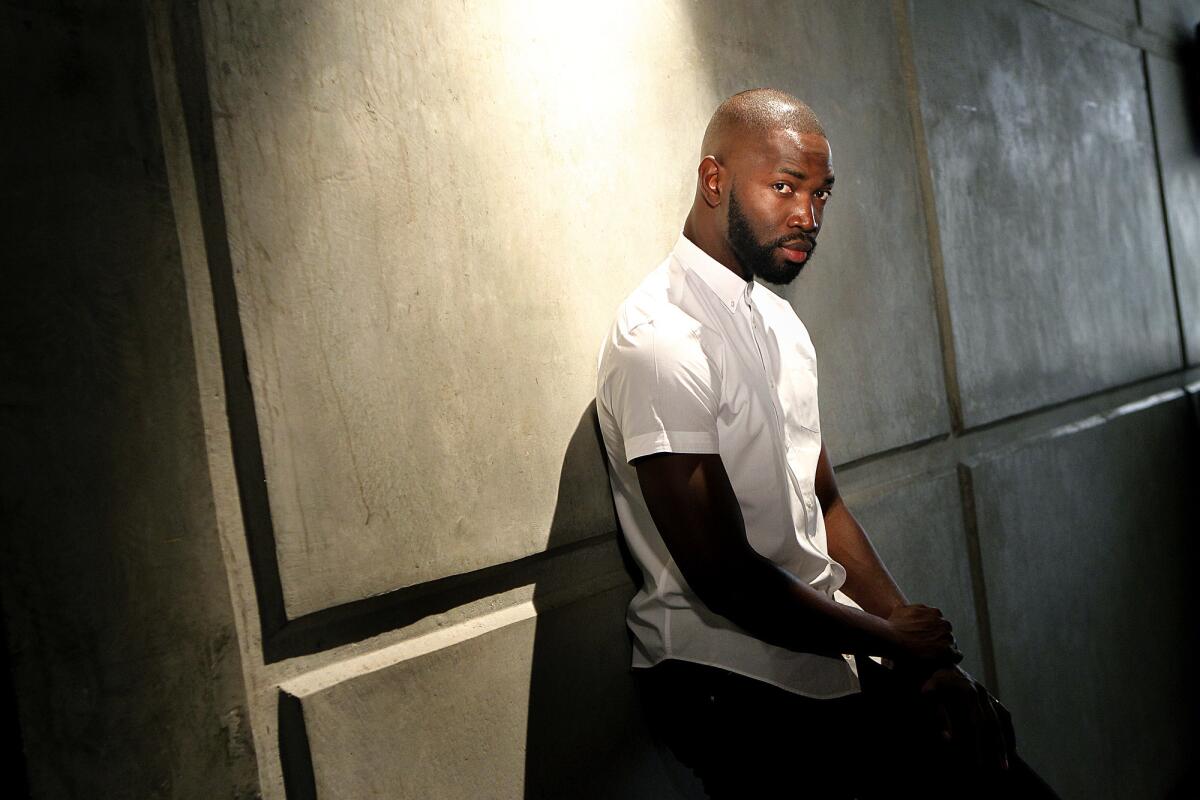

Rising playwright Tarell Alvin McCraney takes his own, wary path to L.A.

- Share via

Tarell Alvin McCraney, one of the brightest American playwrights to come along in some time, showed up for our interview at the Geffen Playhouse with the buttoned-up demeanor of someone about to give testimony before a grand jury.

He occasionally smiled during our hour-long conversation. At a few points there were hints of laughter. But these were fugitive moments. Polite, soft-spoken and admittedly shy, he so rarely lowered his guard that I couldn’t help feeling as though I were sitting at a judge’s bench.

But when you’re young, gifted, gay and black and the theatrical world is toasting you as the next great one, it makes sense to proceed with caution. You never know when the fickle star-making gods will turn on you.

A native of Miami, where he still lives, McCraney was in town for the start of rehearsals of “Choir Boy,” which opens Sept. 26 at the Geffen Playhouse. A few days before we met he participated in a talk-back after a performance of his play “The Brothers Size” at the Fountain Theatre, which had previously produced the L.A. premiere of “In the Red and Brown Water,” the first part of his trilogy, “The Brother/Sister Plays.” (“The Brothers Size” is the middle play, followed by “Marcus; or the Secret of Sweet.”)

To break the ice, I asked him what he had been doing this summer in England, a trip he had mentioned when we were scheduling our meeting. I had assumed that he was in rehearsals with a play at either the Royal Court Theatre (where “Choir Boy” was first done in 2012) or the Royal Shakespeare Company (where he was a playwright-in-residence).

But it turns out this 33-year-old wunderkind who has been collecting prestigious awards since graduating from the Yale School of Drama was in Britain to receive an honorary doctorate from the University of Warwick — quite an honor for a playwright who hasn’t reached midcareer.

McCraney must have detected my bemusement, for his gracious, carefully measured comments were barely audible. He was also modest about receiving a MacArthur “Genius” Fellowship and didn’t even mention the Windham-Campbell Literature Prize, two highly remunerative distinctions that will afford him the time and freedom to write without financial worry for a number of years.

For a playwright who grew up in what he described as “one of the poorest neighborhoods in Miami,” raised by a mother who battled addiction and died from AIDS-related complications when he was 22, this has been some journey.

Yet McCraney was incredibly well prepared. Social programs in the arts were an integral part of his childhood, and he found an early mentor in Teo Castellanos, who directed an improv troupe that McCraney became part of as a teen and later welcomed him into D-Projects, a contemporary dance and theater company that looks at social issues through intercultural performance work.

The beneficiary of what McCraney called “an extraordinary theater education,” he graduated from DePaul University in Chicago before heading to Yale to concentrate on playwriting. Acting was always an interest, and though he hasn’t been focusing on it, he said that it’s not completely out of the picture.

His plays often depict characters fiercely grappling with their destiny, struggling to stay true to themselves while contending with the sharp vicissitudes of life. Has he formulated a philosophy of fate based on his own experience?

“I think the reason you may be sensing this in my work is because it is a fundamental question of the human experience,” he replied. “How much of what I’m doing is will and how much of it is some sort of larger will or mechanism. And how much can I actually fight against this, and will that even lead me back to the path I was ‘supposed’ to be on? I have no hard answers. I know many of my friends do. Some say you make the path by walking, and part of me believes that’s true. Then there’s the saying we’re all here for a purpose, and I believe that may be true too.”

“The Brother/Sister Plays” certainly seemed to have destiny on their side. When these works, which incorporate elements of West African Yoruba mythology, were still germinating inside him, he had a fateful encounter with a Santería priest who told him that he was blessed.

“I met him at a time when I was moving toward something and he called out that something,” McCraney said. “Whether it was through his intuition or because some divination told him, that I can’t be sure.”

Did this encounter give him the confidence that he was on the right writing track? “Any time someone speaks to you on a level that feels knowing, it only invites more fear,” he said.

Yet McCraney’s instincts were apparently in sync with greater forces because these poetically rich, musically enlivened and stylistically adventurous plays, all set in the same Louisiana backwater, have had the American theater buzzing ever since they were presented in workshops at Yale.

Emily Mann, the artistic director of the McCarter Theatre in Princeton, N.J., where the plays were first produced as a trilogy, shared her experience of first encountering McCraney’s work: “Within two pages of reading [‘In the Red and Brown Water’], I was stunned by the beauty and originality of the language, realizing I was encountering an important new voice. I kept reading, wondering who this amazing young writer was, and by the time I finished the play, I knew we had to produce him.”

I first saw “The Brother/Sister Plays” at the Public Theater in New York in 2009. The newness of the style was bracing yet challenging: the spoken stage directions, the mix of high lyricism and street slang, the West African iconography, the communal propulsion into song. I needed more than one encounter with the works to organize my response.

Shirley Jo Finney’s 2012 production of “In the Red and Brown Water” at the Fountain was a revelation. The intimacy of the space and the vibrancy of the ensemble lured me deeper inside the play’s human dimension. Tea Alagic’s production of “The Brothers Size” last year at San Diego’s Old Globe clarified the ritual aspect of McCraney’s vision.

Finney’s touted production of “The Brothers Size,” at the Fountain through Sept. 14, offers a close-up view of this tale of brothers who are opposites yet indissolubly linked. I can hardly wait for “Marcus” to have its L.A. premiere. Stephen Sachs, co-artistic director of the Fountain who was “drawn to the fusion of the mythic and the contemporary” in McCraney’s work and knew that the Fountain was the ideal venue to introduce Los Angeles to this exciting new talent, said he’s interested in producing the third play of the trilogy, though plans have not been set.

McCraney paid tribute to the actors in the Fountain production of “The Brothers Size,” commenting on how well they worked together and how successfully they forged connections with the audience. “The play keeps resonating with what’s happening in our world today,” he said. “That’s the most staggering thing, those moments when you hear the room collectively sigh because of interactions between the black body and the law.”

This was of course a reference to the recent unrest in Ferguson, Mo., over the fatal shooting of Michael Brown by the police, but McCraney said that the focus can’t be about only one set of events.

“I’ve been feeling this way for a while, since we did ‘Choir Boy’ at Manhattan Theatre Club and even before when it was done at the Royal Court, that there’s a lot of healing and conversation that needs to be done,” he said. “I’m not allowing myself to sit in a comfort zone. If that means I write less and read more, so be it. There’s a lot of turmoil in the atmosphere, and if we pretend it isn’t there it will only gas us to sleep.”

McCraney said that although he doesn’t write in direct response to the headlines, he’s “interested in the ways in which things add up.”

“As much as everyone would like to think that ‘The Brothers Size’ is an autobiographical play, my brother wasn’t in jail till after I wrote the play,” he said. “With ‘Marcus,’ everyone asks if it’s my coming-out experience, and I’m like, ‘No, not at all.’ I’m less interested in drawing biographical conclusions than in finding stories that we’re already telling.”

“Choir Boy,” for example, revolves around an elite prep school for African American boys with a renowned choir that is headed by a student who is seen as effeminate. The combustible interactions that ensue shed light on gender, sexual orientation and racial identity. McCraney acknowledged that “while the play itself is new and different, the story at its core is one you’ve seen before.” He finds values in returning to narratives that break open public discussion and believes music is an ideal way of bringing together divergent voices.

Community is integral to his playwriting, both in terms of engaging an audience with provocative social questions and collaboratively tackling creative problems tied to the work with fellow company members. One of his mentors in this regard was the late, great playwright August Wilson, whom McCraney assisted on a production of his final play, “Radio Golf,” at Yale. McCraney didn’t learn how to write an August Wilson play from this experience. He acquired something more valuable: an understanding of what it means to be a generous theater artist.

“He was fierce about the people he wanted in the room and the importance of collaboration, of talking it out, of fighting it out in the room,” McCraney said. “I can be a very shy, introverted person, so sometimes my instinct is to walk away and figure out something by myself and present it to people and then sort of walk away again. But it’s important to trust the people you’ve gathered. This has less to do with art and more to do with heart, with community, with something much more sacred. He could never have sat down and taught me that. He could only show me by example.”

Drama, McCraney emphasized, isn’t a solitary literary endeavor. Words are only one color on the palette. The “cousin arts,” as he dubbed them — music, architecture, dance, painting — can indeed be more of an influence than other plays.

Tall and lean like a dancer, McCraney has great passion for dance — “I have the build but not the talent,” he says — and harbors a dream of one day creating a ballet. In his writing, he tries to conjure similar choreographic effects, “those glimmers when you feel that this isn’t even words anymore, almost like a song, almost like a dance.”

McCraney’s reserved manner can make it difficult to see just how forthcoming he can be. It was only after listening to the tape of our conversation that I realized that his stern facade is misleading, that he’s actually quite genuine and open.

“I’m always very cautious of people and I’m told that I can be intimidating because people can’t always tell what I’m thinking,” he said. “Most of the time I’m thinking: Have I offended someone? Is everything OK? Is it all right to be in this space? Sometimes I’m just thinking about lunch.”

With so many out there eager to claim him as the next great African American or gay playwright, McCraney is smart to keep his cards close to his vest.

“Gay writer, black writer, political writer — the moment I jump into one of those buckets I’m stuck,” he said. “It just makes it harder to hear your own instincts, and there’s already so much noise.”

More to Read

The biggest entertainment stories

Get our big stories about Hollywood, film, television, music, arts, culture and more right in your inbox as soon as they publish.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.