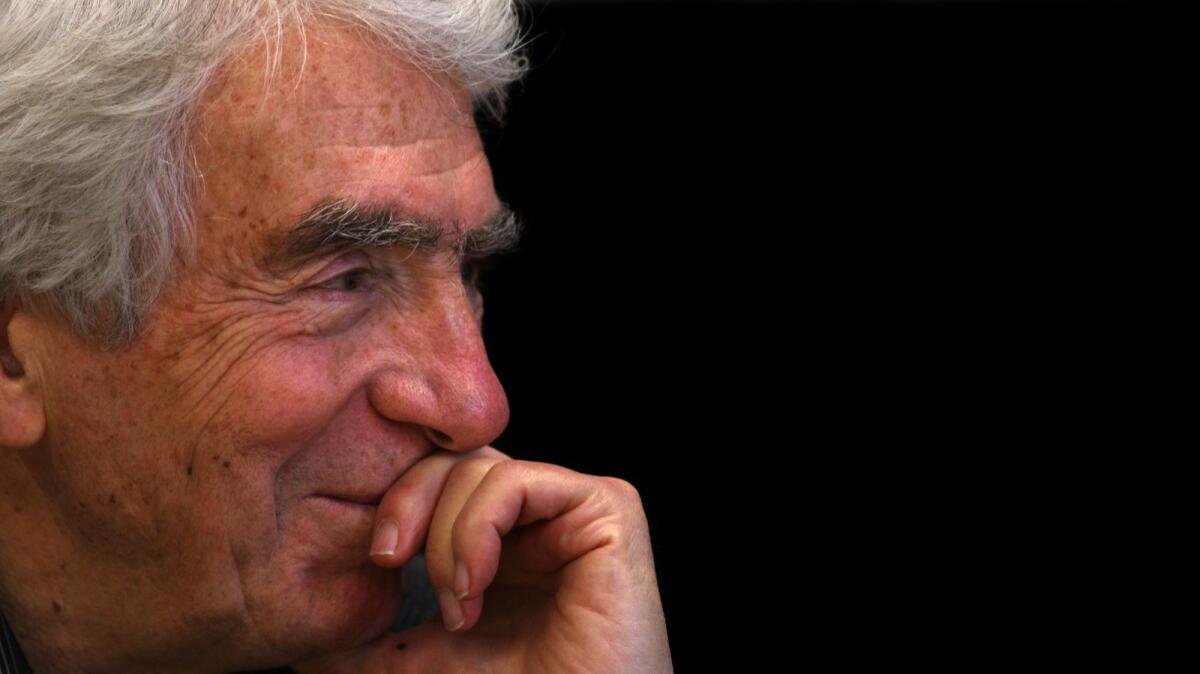

Appreciation: Gordon Davidson didn’t just change L.A. theater, he changed L.A.’s image of itself

- Share via

No one did more to put Los Angeles theater on the map than Gordon Davidson. The founder of the Mark Taper Forum, he was one of the city’s cultural founding fathers, a mild-mannered but determined revolutionary who built Center Theatre Group into the prodigious theatrical institution it is today and, even more important, built an audience with an appreciation for serious drama in this town.

It is impossible to do justice to the dimensions of such a legacy. Davidson’s influence on Los Angeles is twinned in my mind with the architectural landmark just down the street from his old Music Center headquarters — Walt Disney Concert Hall. The reason is that I believe Davidson, who died Sunday at age 83, has done as much to transform the city’s conception of itself as a cultural capital as Frank Gehry’s magnificent building.

Davidson’s campaign against the stereotype of L.A. as a glamorous company town rife with airheads, a place to find fleeting fame and fritter away an obscene fortune, may not have been conducted with flamboyant showmanship. His manner was soft-spoken, shy though not retiring, as affectionate as the smile that would light across his face when he recognized you in the lobby of the theater, always grateful for the chance for an on-the-fly tête-à-tête.

But there was something powerfully centering and clarifying about his presence. He not only represented an institution but he embodied a tradition and a set of enduring artistic values. As one of the heroes of the nonprofit theater movement, he didn’t pay lip service to his principles — they had become inscribed in his genetic code. His integrity was naturally full-throated.

Theater, for Davidson, was an art form shouldering communal responsibilities. It was a forum for societal reflection and collective dreaming, a meeting hall for the voicing of grievances and the thinking through of corrective measures. Zoned for dissent, the stage was simultaneously a place to affirm longstanding beliefs.

Even at its most personal, the theater, Davidson recognized, was engaged in public work. The introspection might be wholly psychological in nature, but carving out a welcoming space for this kind of meditation was a civic act.

For Davidson, theater was a forum for societal reflection and collective dreaming, a meeting hall for the voicing of grievances.

The new work Davidson shepherded at Center Theatre Group by August Wilson, Tony Kushner, Anna Deavere Smith and George C. Wolfe reflected the way poetry and politics were entwined in his sensibility. There was nothing incompatible between social justice and artistic excellence. Davidson knew his theater history — the classics were a regular part of his programming — and so it seemed only reasonable that today’s playwrights would walk down the same path as Sophocles, Shakespeare and Shaw.

When I interviewed Davidson in 2013 when he was co-teaching a seminar at USC that took the students on a guided tour of his life in the American theater, he told me that what he hoped to communicate to the class were what he considered the crucial components of theater, “storytelling and community building.” These two dimensions were inextricably bound in his mind and he feared that money and technology were threatening to pull them apart.

With characteristic modesty, he explained that he wanted to inspire the students by sharing his own story as a director and an institutional leader. He knew that his name didn’t carry all that much weight with them, but when he listed the artists and plays that he developed over the years their eyes lit up. He wasn’t looking for validation from a new generation. He wanted to impress upon his charges that it was still possible to make the seemingly impossible happen. More to the point, it could happen here, in this extraordinarily diverse and talent-rich city — and don’t believe anyone who tells you otherwise.

My tenure as theater critic at The Times began after Davidson had handed over the reins at CTG to Michael Ritchie. But he went out of his way to make me feel welcome from the start, sending me notes on reviews and notebooks and reminding me in person of the value of my work to the theater community.

SIGN UP for the free Essential Arts & Culture newsletter »

I wasn’t here during Davidson’s rocky last years at CTG and so my relationship was untainted by some of the discord and frustration that a few of his close associates would sometimes recall (never mean-spiritedly) in their conversations with me. In some ways I was in the privileged position of a grandchild whose parents don’t always recognize the kindly old figure indulgently telling stories about the past.

But we shared a bond of seriousness. By that I mean our work in the theater was more than just work — it felt to both of us like a calling. Davidson’s father was a theater professor at Brooklyn College, where I taught for years before coming to L.A. He would often remind me of this connection when we talked. He wasn’t buttering me up. He was making a connection over something he worried deeply about — shared values.

The commercialization of the nonprofit theater world disturbed him. He didn’t like to criticize, but as the Taper’s founder he couldn’t help expressing concerns about the place of ambitious drama in a landscape that had become less hospitable, economically and culturally, to what he had devoted his professional life to. When something powerful was presented at the Ahmanson Theatre, the Taper or the Kirk Douglas Theatre, however, he would unreservedly sing its praises — the victory belonging to all of us who love this art form.

It’s only fitting that the last time I saw Davidson was a few weeks ago at the world premiere of a play at the Douglas, the Culver City outpost he launched in 2004 expressly to showcase new voices. His face was bruised and, assuming that he had a fall, I asked if he was OK. He threw a few jabs at the air and joked, “You should see the other guy!”

He was a man of the theater to the end in a city he helped transform into a legitimate theater town.

Follow me @charlesmcnulty

ALSO

Obituary: Gordon Davidson, L.A.’s ‘Moses of theater,’ dies at 83

Obituary: Neville Marriner, L.A. Chamber Orchestra director and ‘Amadeus’ maestro, dies at 92

Mike Daisey’s one-man show, ‘The Trump Card,’ delves into the Donald phenomenon

More to Read

The biggest entertainment stories

Get our big stories about Hollywood, film, television, music, arts, culture and more right in your inbox as soon as they publish.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.