Review: Jim DeFrance retrospective at Doyle Arts Pavilion is a dazzler

- Share via

Jim DeFrance (1940-2014) made abstract paintings that analyze more than accept, cogitate more than assume. Poetry eclipses prose, often with color as primary language.

A modest retrospective of around 30 paintings and works on paper, co-curated by Tom Dowling and Trevor Norris for the Doyle Arts Pavilion at Orange Coast College in Costa Mesa, offers a welcome opportunity to become reacquainted with DeFrance’s art, which isn’t often seen. The high-flying Neo-Expressionist juggernaut that swept through art in the 1980s, followed by the 1990 market crash, didn’t leave much room for an abstract painter of DeFrance’s manner.

His exposure was limited after 1987, following a string of closely watched solo shows over nearly 20 years at Nicholas Wilder and Jan Baum galleries. “Jim DeFrance: A Retrospective” is a concise and worthy reintroduction. More a thumbnail sketch of a career than a full accounting — necessary given the venue’s limited space — it succeeds in sparking interest to see more.

Oddly, if one juxtaposed an early painting with one of his last, it might initially look like two different artists had made them. The abstract motifs vary widely, but the survey also reveals a through-line of impeccable craftsmanship.

Deskilling is the currently fashionable, sometimes useful effort to eliminate the value given to artisanal competence. The aim is to shake up and destabilize institutionalized judgments of aesthetic worth.

But deskilling was not a part of DeFrance’s vocabulary — perhaps because his work was launched at a moment when the pristine aesthetic of finish fetish art, the so-called L.A. look, was ascendant. The path of DeFrance’s work after 1965, the year he graduated with an MFA from UCLA and had his first gallery appearance in a group exhibition, is long and winding.

It began with a bang.

“Dazzler,” one of the earliest works on view, is an Op extravaganza that melds chromatic dissonance (diagonal stripes of turquoise and vermilion) with physical and optical shape-shifting (a skewed, 10-sided canvas with an interior jigsaw-puzzle composition of interlocking and overlapping rectangles and triangles). Frank Stella’s paintings are a likely inspiration, but with a slight difference.

A pair of cut-out trapezoid shapes in the middle of the canvas makes negative space — actual, not illusionistic — essential to the composition’s success. DeFrance introduced an element of the new, environmental Light and Space art into painting.

Light and Space artists like Doug Wheeler and Robert Irwin were leaving painting behind — dematerializing the art object, in critic Lucy Lippard’s famous phrase — while Larry Bell was moving into sculpture. DeFrance refused to let painting go.

His next works, which launched his solo gallery career, were the so-called “slot paintings.” Minimalist, mostly monochrome canvases featured geometric patterns of cut-out rectangular slots.

“Saint Cloud,” 6 feet high and 12 feet wide, is emblematic: a black canvas pierced by six evenly spaced rows of seven horizontal slots. The cut-outs expose the wall on which the painting hangs, but slow perusal begins to reveal vaporous flickers of pale color within the neat lineup of empty spaces.

The work’s framing stretcher bars are unusually deep — maybe 3 or 4 inches — which allows light to circulate behind the picture plane. The optical haze arises from reflections of a rainbow of color blocks that DeFrance painted in an irregular pattern on the back of the canvas.

For the viewer looking at the front, hints of soft light lurk within the overall darkness. You practically want to crawl inside the painting to discover what is happening — and how.

Interactivity with a viewer is a hallmark of DeFrance’s work, which is positioned as a meeting point between artist and stranger. One later piece, 1984’s “Flywheel,” is even a functional credenza, furniture whose colorful surfaces constitute a three-dimensional painting pushed up against a wall.

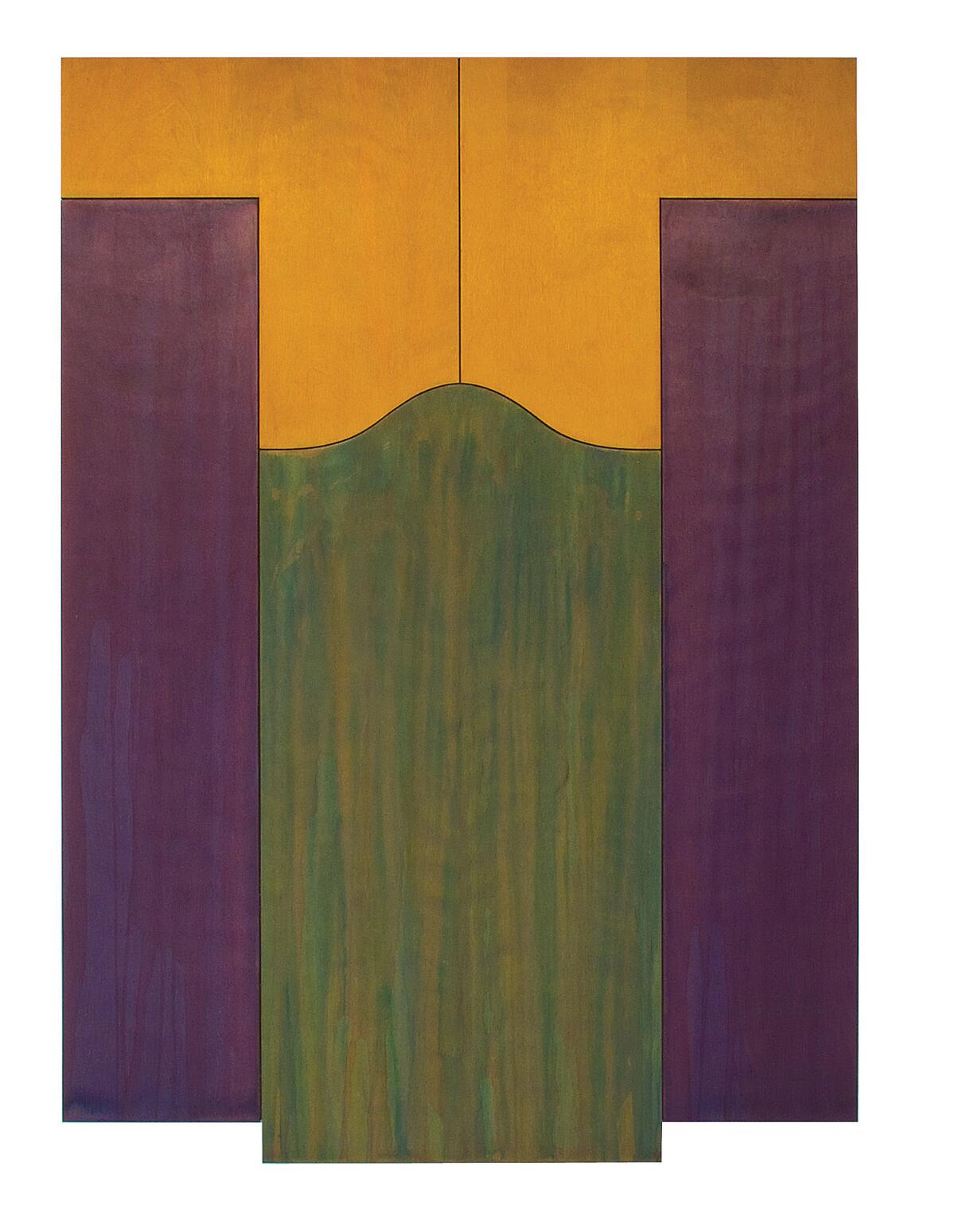

The show moves quickly through a variety of series. There are paintings with woven geometric patterns, some with combed and fluid surfaces, a few seemingly aerial views of abstract landscapes and a pair of doorway-like constructions made from interlocking shapes and implying passages into other realms.

A group of eccentrically shaped panels of wood veneer painted in wavy stripes of snazzy, multicolor acrylic is inexplicably mesmerizing. DeFrance was a gifted colorist, and his hues tend toward the tertiary — rather than a purist’s red, yellow and blue, for example, he gives us magenta, chartreuse and teal.

The concluding works, made after 2000 and the dawn of a new millennium, are precisely crafted, interlocking panels of softly stained birch wood — perceptually quiet and meditative in the extreme. According to the show’s small catalogue, some are inspired by Japanese Zen brushwork (one is named for the gate of a Shinto shrine), while others are tagged for birds and for monumental, prehistoric stone monoliths.

The stained panels, although softly hued, bring you back to “Dazzler,” whose clashing colors of cinnabar and turquoise signal spiritual elements of celebration and healing within Asian and Native American cultures. (DeFrance was born in Alliance, Neb., a region rich in Native American tribes.) The early and late works look nothing alike, but they do fit easily together.

Frank M. Doyle Arts Pavilion, Orange Coast College, Merrimac Way, Costa Mesa. Through April 7. (714) 432-5738, https://www.orangecoastcollege.edu

Twitter: @KnightLAT

ALSO

Hammer Museum receives $50 million in gifts for expansion

Frieze to launch a Los Angeles art fair at Paramount Studios in 2019

Takako Yamaguchi's portraits won't look you in the eye

Judy Fiskin's funny, thought-provoking confessions of an iPhone addict

The biggest entertainment stories

Get our big stories about Hollywood, film, television, music, arts, culture and more right in your inbox as soon as they publish.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.