A vast Louis Kahn retrospective lands at the San Diego Museum of Art

- Share via

Given the substantial shadow his work continues to cast on the profession, it’s a little surprising that “Louis Kahn: The Power of Architecture,” a vast exhibition organized by the Vitra Design Museum in Germany and running at the San Diego Museum of Art through the end of January, is the first major retrospective of Kahn’s career to appear since the Museum of Contemporary Art in Los Angeles put one together a full quarter-century ago.

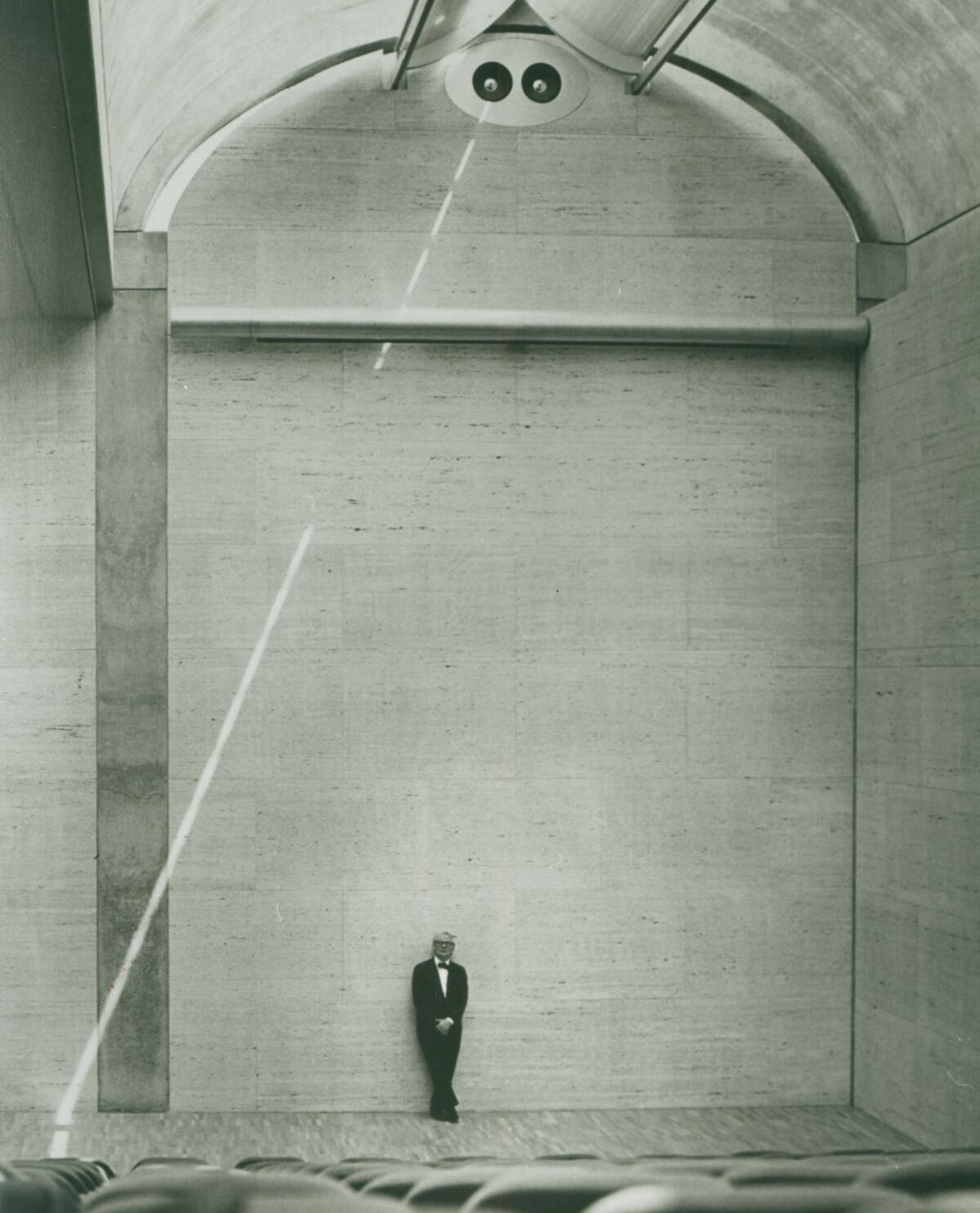

Curated for its California run by the SDMA’s Ariel Plotek, the Vitra show gains new layers of meaning — and will be read differently by its American audience — simply by being reassembled less than 15 miles from one of Kahn’s most brilliant designs, the 1965 Salk Institute for Biological Studies in La Jolla.

And it’s a pleasure to walk through, densely packed as it is with models, photographs and sketches of Kahn’s astonishingly self-possessed buildings, which rise in locations as scattered as Ahmedabad, India (the Indian Institute of Management, 1962); New Haven, Conn. (where the 1953

What the show doesn’t do is reflect much of a desire to reassess — to re-litigate, as the Sunday morning talk-show guests like to say these days — the relationship of Kahn’s work, which was embedded in an interest in history bordering on the obsessive, to that of his peers or his era. Challenging the conventional wisdom about Kahn, that he was an exile from the architecture profession for much of his career and proud to be one, is not among its top priorities.

Nor does the exhibition manage to draw any connections with a new interest in the uses of history that has begun to stir among some of the most talented emerging and mid-career architects in this country and around the world. Because it opened more than three years ago at Vitra and was in the planning stages well before that, its view of the role of history in architectural practice remains, well, somewhat buried in the recent past.

But first to that conventional wisdom. Historians, critics and architects alike have tended to think of Kahn’s work as so suffused with timelessness and monumentality that it deserves to stand well apart from the standard chronology of the field.

In an intensely productive (as opposed to merely prolific) period between the early 1950s and his death in 1974, he turned out roughly a dozen supremely consequential projects: houses, museums, libraries and laboratory buildings that were stripped of ornament but happy to take on the weight and even the symbolic burdens of history.

In that period, essentially the high point of architecture’s modern movement in this country, those preoccupations were thought to be incompatible. Modern buildings shed decoration as a way of wiping the historical slate clean; buildings that were explicitly interested in history were, essentially by definition, not modern.

Especially after a revelatory stay at the American Academy in Rome that began in 1951, the year he turned 50, Kahn was more interested in what his work could learn from the strength of classical ruins than from battles within the profession.

Even as a classically inflected and historically minded postmodernism gained confidence at the end of the 1960s and beginning of the 1970s, led by

Kahn belonged, or was assigned, to an architectural category of one. (“It was just quietly accepted that he stood alone in creative stature,” Ada Louise Huxtable wrote in the New York Times after his sudden death. “He seemed out of step with his times.”) He was a historian and an inventor, a modernist who looked back.

His work was radically new — capable of remaking the profession, in fact — in large part because of the way it seemed to emerge, fully formed, from some deep, shrouded history. The buildings, solid, massive and often sphinx-like, with an unmistakable sense of compression, also took themselves pretty seriously.

“From the very beginning he was after symmetry, geometric clarity, primitive power, enormous weight,” the Yale historian Vincent Scully, who lobbied for him to get the Yale art gallery commission, once said, stacking each of his words like the bricks in a Kahn facade. “A permanent work in the world.”

Directly or indirectly, the exhibition gets at all of that and gives a fair indication of why Kahn, who was born in Estonia in 1901 and arrived with his family in this country four years later, was such an unusual and sometimes unfathomable figure in the architecture of the early postwar decades.

Divided into six thematic sections, the exhibition considers Kahn’s work in relation to urbanism, science, history, landscape, community and domestic architecture. (For the details of his own complicated domestic life, which included a long marriage that produced a daughter but also children born to two other women, you’ll want to go back to the remarkable 2003 documentary “My Architect,” directed by one of those children, Nathaniel Kahn.)

The show argues that Kahn operated in a moral sphere rather than a careerist one. “In today’s world,” as one bit of wall text puts it, “where the act of building is increasingly subordinated to marketing strategies and financial speculation, Kahn reminds us of the age-old significance of architecture as the universal conscience of humanity.” Which is one way of admitting, I guess, that he was a lousy businessman.

The curators make a point of exploring the interest in science, technology and engineering that propelled much of Kahn’s architecture, especially early in his career. A model of his unbuilt City Tower, a proposal that structurally and otherwise owed a great deal to research on DNA and the double helix, stands near the entrance. Kahn collaborated on the tower project with Anne Tyng (with whom he also had a daughter, Alexandra).

What the show doesn’t do in much depth is explore the ways in which the familiar readings of Kahn’s work come up short. The truth is that he and his work weren’t quite as isolated as we like to remember. Marcel Breuer (particularly in his Whitney Museum of 1966), Paul Rudolph, Edward Larrabee Barnes,

SIGN UP for the free Essential Arts & Culture newsletter »

Thanks to both timing and its faithfully monographic point of view, “Louis Kahn: The Power of Architecture” also steers clear of exploring what Kahn’s architecture might mean for the growing group of contemporary architects, mostly in their 30s, 40s and early 50s, who are casting about for fresh and productive ways of treating history, tradition and the vernacular. These architects include L.A.’s Sharon Johnston and Mark Lee; India’s Bijoy Jain; Burkina Faso-born, Berlin-based Francis Kéré; Swiss firm Christ & Gantenbein; Chile’s Alejandro Aravena and Smiljan Radic; and China’s

Their interest in the past is quite different from that of the post-modernists in the sense that it’s far more earnest (sometimes to a fault) than cheeky and steers well clear of nostalgia and pastiche. It’s a reaction not to modernism but to a more recent hegemonic force in the profession: the flamboyant geometries and celebrity architecture that dominated coverage of the field over the last two decades. It wants to anchor itself in something other than the overwrought form-making of architects like Daniel Libeskind,

Does this emerging interest in history, then, owe a clear debt to Kahn? Yes and no. It does seek a similar clarity of shape and line and in some cases a similar kind of substance, of physical weight or even explicit primitivism. It is most of the time lighter in spirit, less shamanic, less ponderous or mystical in its outlook than Kahn’s buildings (or those of the Swiss architect

Happily, anyone hoping for an in-depth investigation of this emerging sensibility won’t have to wait past next fall. That’s when the second installment of the Chicago Architecture Biennial will open, directed by Johnston and Lee.

As the pair put it in a curatorial statement released a few weeks ago, “a renewed interest in history and precedents of architecture has been emerging among a new generation of architects.” The biennial, they added, will reject the “insistence on being unprecedented” that has been so prominent over the last two decades in architecture and focus instead on those firms working to “make new history.” Kahn would surely approve.

Twitter: @HawthorneLAT

ALSO

The Crystal Cathedral redesign: Why tasteful updates add up to architectural disappointment

George Lucas' museum designs for L.A. and S.F.: A first look at competing plans

Martin Luther broke Europe in two, and Albrecht Dürer painted it back together

The biggest entertainment stories

Get our big stories about Hollywood, film, television, music, arts, culture and more right in your inbox as soon as they publish.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.