Expect the unexpected on recordings of Kent Nagano and Orchestre Symphonique de Montréal

- Share via

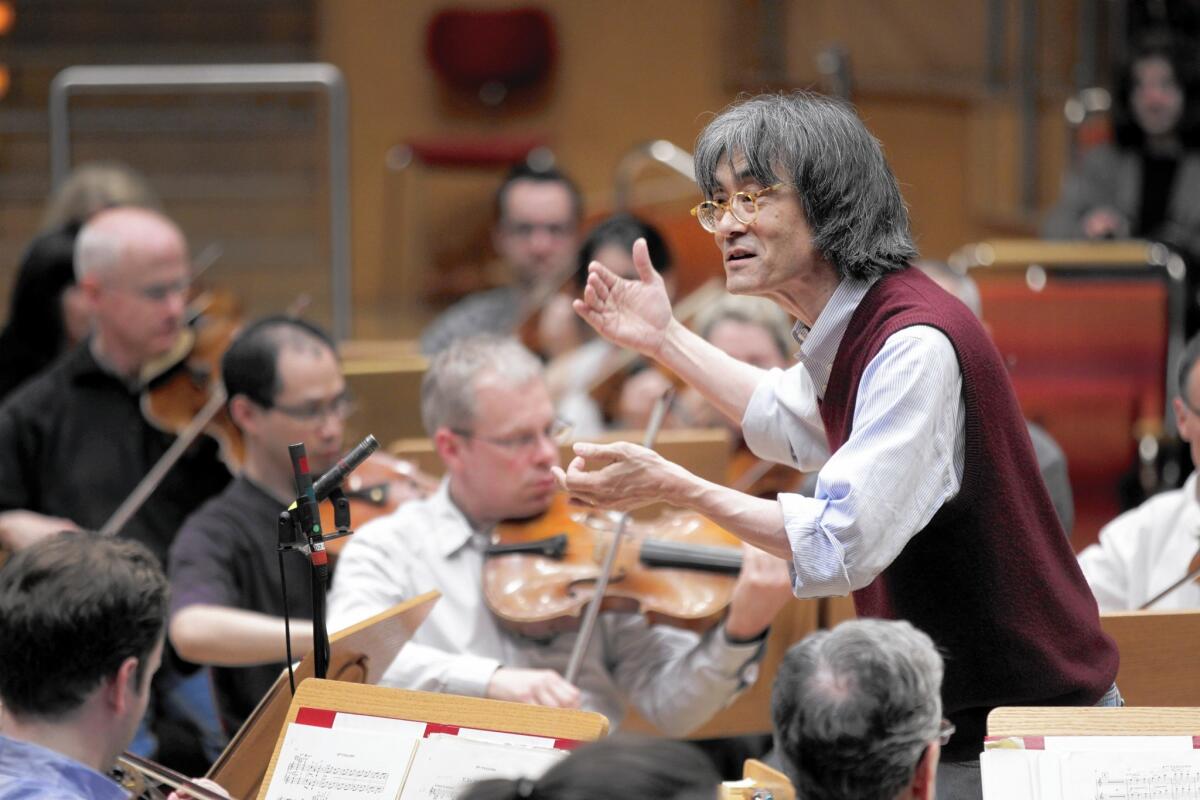

It should be common knowledge that Kent Nagano, who arrived in California this week amid his first U.S. tour as music director of the Orchestre Symphonique de Montréal, is one of the world’s most imaginative and important conductors.

He headed the Berkeley Symphony for three decades and served as Los Angeles Opera’s first music director. And he’s just begun his first season as music director of the Hamburg State Opera and Philharmonic (which will make news next year when a new Herzog & de Meuron-designed hall opens).

Yet Nagano is inexplicably absent from the guest conducting lists of major American orchestras or opera companies. Readers suffer too; his 2014 book appraising the current musical situation has been published only in Germany as “Erwarten Sie Wunder!” (Expect the Unexpected).

SIGN UP for the free Classic Hollywood newsletter >>

Now, as further unexpected insult added to injury, no venue in Los Angeles or Orange counties has shown interest in booking Nagano and the Orchestre Symphonique de Montréal, which arrived in Palm Desert on Tuesday. The troupe heads to San Diego (Wednesday) and Santa Barbara (Thursday) before continuing on to Northern California.

Nagano has had other notable orchestra and opera appointments in France, Germany, England, Sweden and Russia. Born in California of Japanese heritage, Nagano has an avid following in Asia and is married to Japanese pianist Mari Kodama.

But where Nagano can be heard is on a series of outstanding recordings with the Orchestre Symphonique de Montréal over the last decade.

These include a Beethoven symphony cycle, Mahler recordings with German baritone Christian Gerhaher (“Das Lied von der Erde” is a must) and Unsuk Chin’s phenomenal Violin Concerto, all of which show the Montrealers to be in gorgeous shape.

The latest are two seemingly less significant releases on the Analekta label revolving around Saint-Saëns. Expect the unexpected. For one thing, there is Montreal’s orchestral sound, which has acquired a burnished and near mystical warmth under Nagano.

For another, there is Analekta’s showcase recorded sound, the finest I’ve heard of an orchestra in some time. If you have the equipment to play hi-res digital files, you can find them (at remarkably reasonable prices) on the Analekta website.

Each release features a famous, and over-recorded, Saint-Saëns’ Third — the Symphony No. 3 and Violin Concerto No. 3. But Nagano places each score in an unusual context. The symphony, which features organ, is surrounded by recent works for orchestra and organ by Samy Moussa and Kaija Saariaho that Nagano commissioned for the OSM.

A 31-year-old composer from Montreal, Moussa is a dazzling colorist, and his “A Globe Itself Unfolding” glowingly immerses the organ in an ocean of orchestral sonorities. Saariaho’s “Maan Varjot,” which the Los Angeles Philharmonic performed in 2014, explores cooler and harsher but highly original organ/orchestra colors. The soloists are the orchestra’s emeritus organist, Olivier Latry, and its resident one, Jean-Willy Kunz.

For a survey of Saint-Saëns’ three violin concertos, Nagano relies on the OSM’s suave young concertmaster, Andrew Wan. What is unexpected here is that the little-known first two concertos are worth the excavation for their melodic freshness and verve, while the third, a virtuoso showpiece, sounds just as fresh when played with reserve and class.

Sonically, Nagano’s refinement stands in considerable contrast to the more brightly colored and detailed OSM sound that previous music director Charles Dutoit made famous in a series of spectacular Decca recordings produced in the early digital age. But Decca has now signed the orchestra again, and the first release with Nagano is a find: an obscure French opera, “L’Aiglon” (The Eaglet), jointly composed by Arthur Honegger and Jacques Ibert.

Thanks to its overt French nationalism, the opera, which focuses on the hopes of Napoleon’s son to escape the Austrian court and return to France, was suppressed after its Opéra de Monte-Carlo premiere in 1937. The Nazis got the point.

The score is uneven. Honegger was the better composer, while Ibert proved the more operatically engaging. Ibert’s dances are lighthearted and his music for the Eaglet’s death scene is touching. Honegger supplies substance and revolutionary fervor. The Eaglet (sung by Anne-Catherine Gillet) is a soprano role, as is that of his lover, Thérèse (Hélène Guilmette), which gives their encounters an innocently becoming brightness even if they are always farewells.

Decca’s engineers expect the expected in their attempt to revive on record the crystalline OSM sparkle of old. That’s not entirely inappropriate, given the quantity of sparkle that “L’Aiglon” supplies and the careful attention Nagano pays to telling details. But this orchestra no longer needs Dutoit’s brilliance. Nagano has taken it to less obvious, more ethereal realms.

More to Read

The biggest entertainment stories

Get our big stories about Hollywood, film, television, music, arts, culture and more right in your inbox as soon as they publish.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.