Critic’s Notebook: Why is the Petersen Museum ignoring Von Dutch’s racist past?

- Share via

If an art museum today were to open a group exhibition that featured, without comment, the work of an avowedly racist and anti-Semitic contemporary artist, all hell would break loose.

The anger would be justified. Surely stern requests for an explanation would follow, or even furious demands for removal. I shudder to think what the repercussions might be.

Apparently, those rules don’t apply to pop culture museums.

Without a ripple of discontent, just such an exhibition had its recent debut at the Petersen Automotive Museum, the place with the flashy spaghetti-facade at the corner of Wilshire Boulevard and Fairfax Avenue. “Auto-Didactic: The Juxtapoz School” opens with an appalling, if muffled, blast.

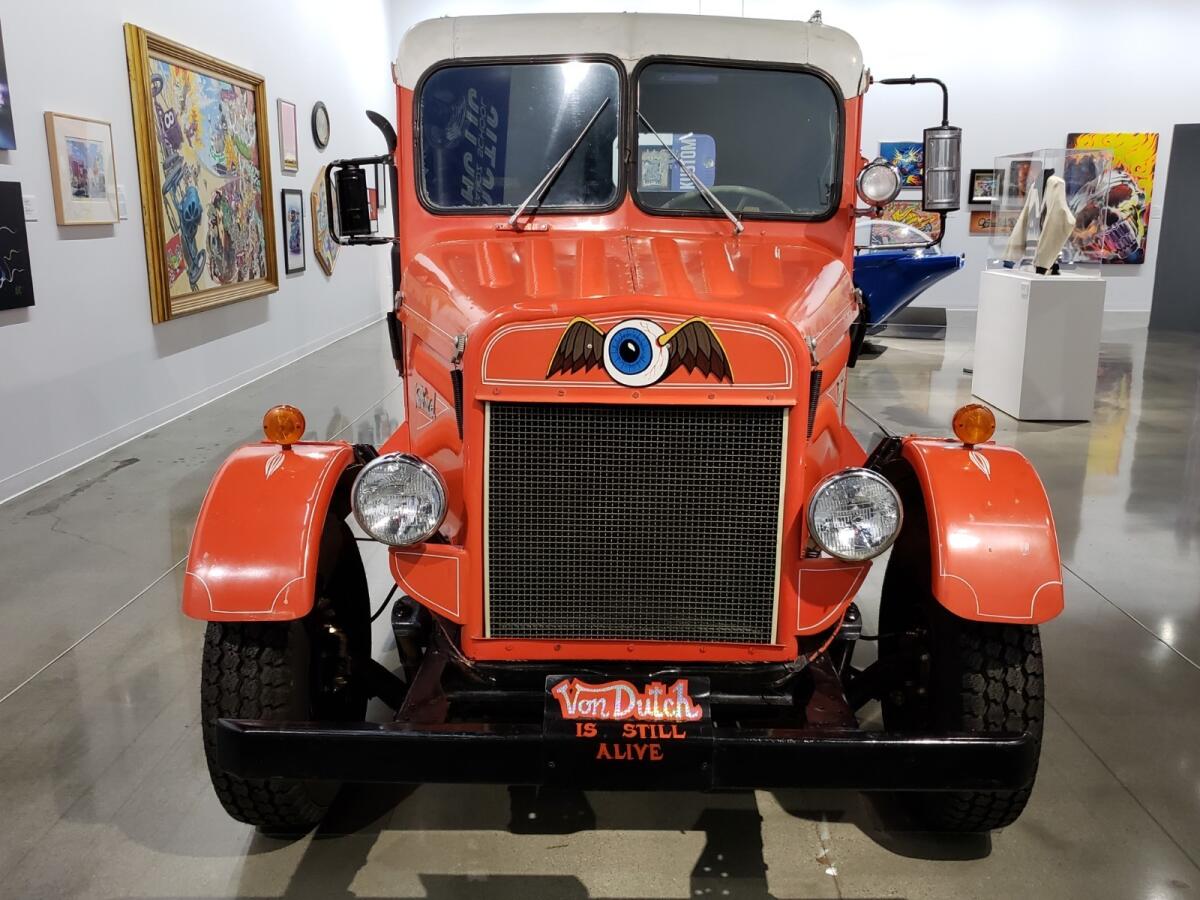

The “Kenford Truck” (circa 1970) launches the survey. The custom pickup was made by Kenneth Robert Howard (1929-1992), better known as Von Dutch, the Prince of Pinstriping. A mid-career example, made for the Los Angeles artist to drive, the pickup is lavishly machined and exquisitely pinstriped.

Von Dutch was, by his own admission, a racist admirer of the Third Reich. A letter he wrote about abandoning harsh medical treatment for a fatal illness is blunt:

“I am not willing to go through it anymore only to emerge in a place full of [N-word], Mexicans and Jews. … I have always been a Nazi and still believe it was the last time the world had a chance of being operated with logic. What a shame so many Americans died and suffered to make the rich richer and save England & France again, or was that still. I hope you lying wimps get swallowed up with your stupidity.”

Pinstriping uber alles.

Howard was an apparent alcoholic. (He altered the Kenford truck to include a handy chute from cab to pavement for the disposal of empty beer cans.) His shocking letter, written not long before liver disease killed him, was reprinted in a comprehensive 2004 Los Angeles Magazine profile by R.J. Smith.

The origin of Howard’s pseudonym is uncertain, but “Von Dutch” reflects the Americanization of Deutsch, the word for German, much the way Pennsylvania Dutch came to be applied to the state’s German-speaking inhabitants after the 18th century. “Von” added a flourish of nobility, a declaration of whence his spirit came. He crowned himself with a legacy not widely revered in the aftermath of slaughter in Stalingrad and Normandy.

But the show whitewashes Von Dutch. His outrageous bigotry goes unmentioned, and Lowbrow art is lazily plugged into a romantic idea that modern art is born of alienation. He is cast as merely the crotchety father of Lowbrow art, a rambunctious counterculture movement fostered by a sometimes-obnoxious rebel railing against the conformity of postwar America, an art later promoted by Juxtapoz magazine.

For the Kenford, the hulking cab of a 1947 Kenworth truck is fused onto a durable 1956 Ford chassis. The unique hybrid is further monogrammed with the artist’s famous logo of a bloodshot eyeball with wings, painted on the doors and hood. The flying eyeball also turns up as a silver metal cutout on the tailgate.

It is not difficult to see Howard’s jaunty “Flying Eyeball” logo, which dates to 1948, as an adolescent’s malicious cartoon riff on the wreathed swastika surmounted by a winged eagle, sometimes called the Wehrmacht Adler, that was an emblem of recently defeated Nazi Germany. Sent aloft on flapping wings, the artist’s all-seeing eye, bloodshot from booze, replaces the Nazi hooked cross nestled inside the circle of a victorious laurel wreath.

On the Kenford truck’s tailgate, the artist lettered in German Haus von der Flieger Augen — “From the house of the flying eyeball” — around the metal cutout. Von Dutch was not a nice man.

Born in 1929 near Compton, he was a fetid product of wrenching social and economic transformations underway across the United States. African Americans in the Second Great Migration were fleeing the cruelty of the Jim Crow South and seeking work in L.A.’s burgeoning military and aerospace industry. Under fierce protest, his Compton neighborhood went in a single generation from middle-class white to middle-class black.

Dramatic social tensions fueled the region’s flourishing John Birch Society, which opposed the civil rights movement. They framed the experience of Richard Nixon, raised in nearby Yorba Linda, who would embrace a 1968 Southern Strategy of racial polarization to get to the White House, forging a Republican template for presidential electoral politics exploited by Ronald Reagan in 1980, George H.W. Bush in 1988 and Donald J. Trump in 2016.

The rise of L.A. car culture was instrumental in cementing these divisions, balkanizing neighborhoods with freeway barriers and facilitating white flight to the suburbs that, even today, has left the city one of the nation’s most segregated. Yet, incongruously for an automotive museum, none of this will be found in the Petersen exhibition, nor in the catalog that accompanies it. That omission includes Howard’s neo-Nazi hate.

There are productive ways for a serious museum to address it. In Massachusetts this summer, I saw an excellent example at the Worcester Art Museum.

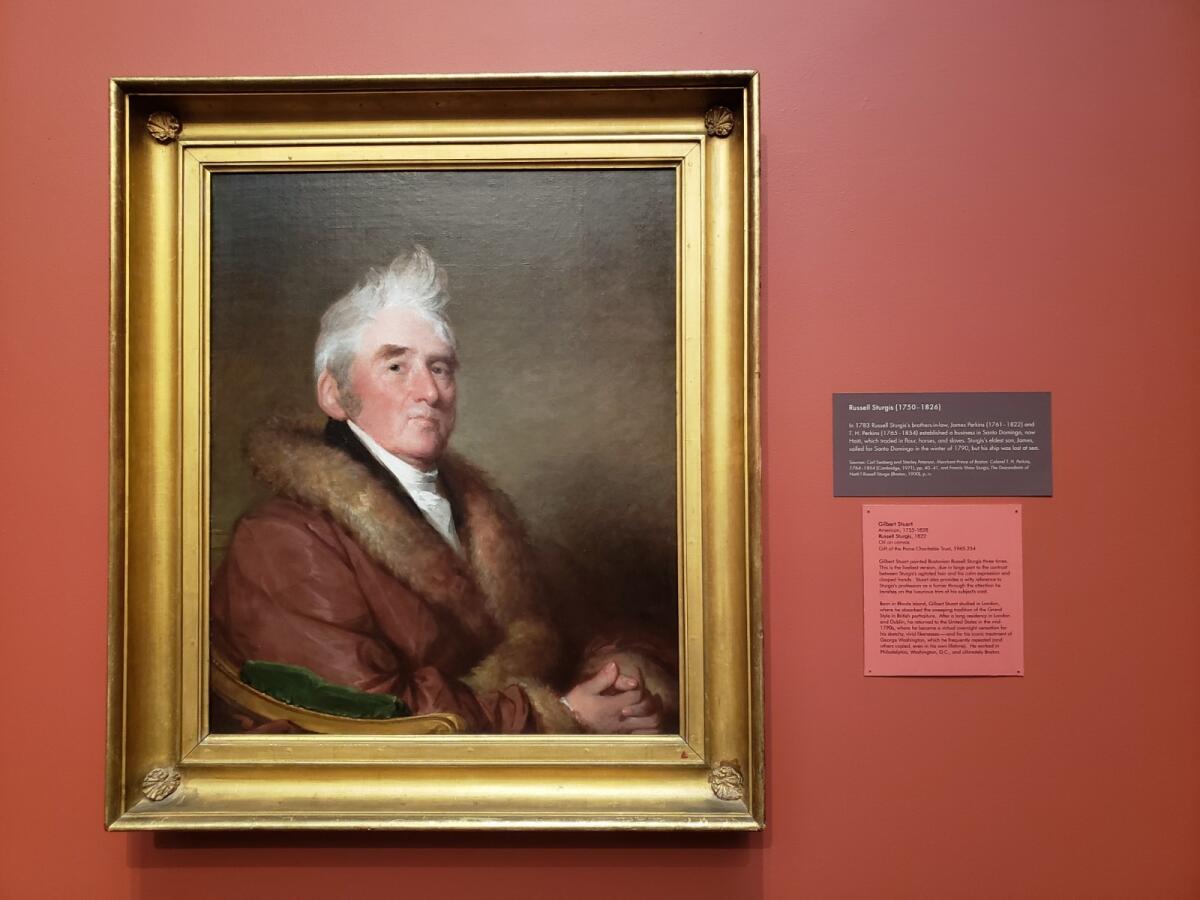

New signage appended to its exceptional collection of 18th and 19th century American portraiture by John Singleton Copley, Gilbert Stuart and other Boston artists added information about the sitters’ status as slaveholders. The horror of chattel slavery contributed to the wealth that made luxury items like commissioned portraits possible, while the whiteness of all the paintings’ sitters was silently italicized.

The museum’s wall texts are straightforward and not accusatory. Just the facts, ma’am: State Sen. Russell Sturgis had a booming business trading flour, horses and human beings in the Dominican Republic, while lovely Lucretia Chandler Murray, daughter of the local sheriff, led a life of leisure abetted by the unpaid labor of servants Sylvia and, echoing the city’s name, Worcester. African slaves in 18th century Massachusetts come into view for museum visitors, where before they were erased.

Art’s history is amplified. So is the art museum’s function in society.

None of this is to suggest that any of the other artists in the Petersen’s “Auto-Didactic” show, nor its curators and the genre of Lowbrow art itself, signed onto Von Dutch’s deplorable worldview. Neither should his unruly work be censored, banished from public galleries.

For good and ill, given his unabashed talent and influence, he belongs at the show’s entry. But rather than whitewash Von Dutch, the museum’s obligation is to wrestle with the truth.

Counterculture? No. Von Dutch was a reactionary. He occupied an extreme, dystopic end of a powerful mainstream of racial animus, a cultural catastrophe papered over but prominent in post-civil rights American life for 60 years — the period the show surveys.

“Auto-Didactic” features mostly modest paintings, drawings, graphics and other mixed media art, including four extravagantly customized vehicles, by 51 post-World War II Lowbrow artists working in Southern California. Their common subject matter is here focused on hot-rod culture, as befits the museum’s automotive theme.

The compact survey, organized by Petersen curator Joseph Harper and guest curator Craig R. Stecyk III, a leading chronicler of skateboarding and surfer culture, is crowded into a tight gallery space. The story begins with a collage, a painting, a decorated sweatshirt and the truck by the movement’s artistically gifted, personally foul fountainhead.

Before he was 10, Howard was hand-decorating mass-produced cars. By the time he was 18, the blond, blue-eyed, flat-topped dude could turn a steady, vaulting painted line into a razor-sharp, whiplash interlace that would briskly animate the deadened surface of an otherwise soulless machine.

Inert, cookie-cutter industrial products were a trait of post-World War II America. Focused hostility to that flood of stuff drove Von Dutch’s highly individualized efforts. Pinstriping personalized a common machine, art was a power to be used to fix an inherent industrial flaw.

Lowbrow art is almost always unhelpfully framed as an aesthetic argument between art for “the people” versus art for “the snobs,” as it is again here. Hogwash. Snobbism, which equates social status and human worth, is as reactionary as it gets. Von Dutch was a racial snob.

Ignoring that vile reality does a disservice to Ed “Big Daddy” Roth, Robert Williams and Kenny Scharf, the talented makers of the three other custom cars on view, not to mention the rest of the show’s artists. Everyone here shares a ride in the same shabby roadster, as art history is mythologized and sanitized – made safe for entertainment consumption.

For Lowbrow art, that might be the unkindest cut of all. For a museum, it’s obtuse.

Twitter: @KnightLAT

More to Read

The biggest entertainment stories

Get our big stories about Hollywood, film, television, music, arts, culture and more right in your inbox as soon as they publish.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.