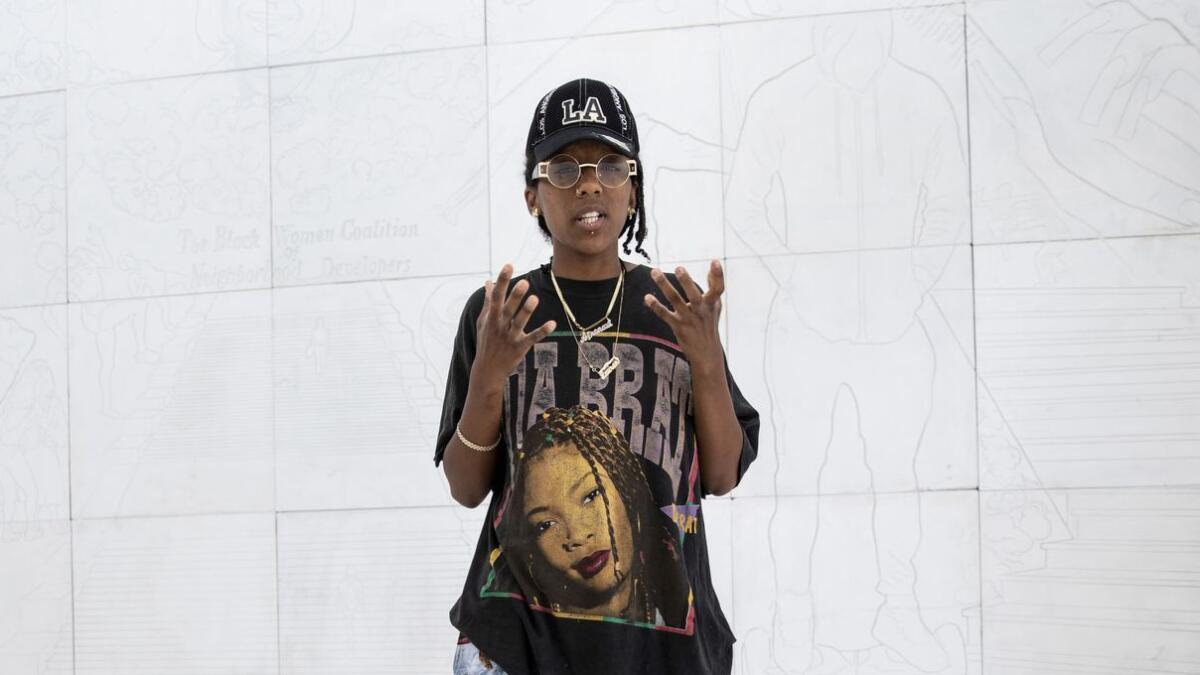

In installations at the Hammer and MOCA, Lauren Halsey riffs on the nature of space and black identity

- Share via

On the second story of the Hammer Museum stands a monument to Los Angeles.

Glance at it fleetingly and you might confuse it with an ancient Egyptian temple, walls crafted from gypsum panels covered in the sinuous outlines of bas-relief. Draw in closer, and the designs come into focus: a low-rider, palm trees and the patterns of the braids on a young girl’s head — as well as Marcus Garvey, the Pan-African nationalist who was active in the early 20th century, looking regal in a plumed hat in one corner.

This is a contemporary monument. But it also contains nods to the ancient: an eye of Horus, a bust of Egyptian queen Nefertiti and a sphinx. Yet the image that inspired this sphinx doesn’t hail from Egypt — it’s from Los Angeles.

“There was an amazing South-Central sphinx that someone built and it’s on their front lawn,” says Lauren Halsey, as she scrolls through her phone to find the photo she recently snapped. “It’s made out of papier-mâché.”

Monuments are the sort of thing that are generally imposed on the public from the top down: a government, civic or artistic authority manifesting its presence in bronze.

Halsey’s monument is quite the opposite.

For years, the artist, 31, who was born and raised in South L.A., has been working on a concept for a public monument that would in some way record and pay tribute to black life in the neighborhood that she is from. It’s a monument she aims to build collaboratively — with the aid of family, friends and fellow residents in South Los Angeles — and in a permanent fashion. She is working to find a site along Crenshaw Boulevard that could accommodate the structure.

“I have no interest in building huge structures for myself,” she says of the idea. “They are about neighborhood. They are about unity.”

The piece on view at the Hammer Museum is a fully realized prototype of that idea, presented as part of the museum’s “Made in L.A. 2018” biennial, on view through early next month.

Certainly, “The Crenshaw District Hieroglyph Project (Prototype Architecture),” as the piece is titled, is impossible to miss.

There is its scale: The central structure is 12 feet high and 20 feet deep, and the installation occupies the entire expanse of the museum’s sun-dappled Lindbrook Terrace.

But more significantly, there are the ways in which it deftly weaves together art and architectural history, creating a record of the quotidian — graffiti, commercial signage, people on the street — while also touching on the cosmic. Halsey is a devoted collector of objects and images related to the more psychedelic corners of African American mysticism. Think: pyramids, ankhs, George Clinton and the Mothership.

“It’s black genius, black science,” she says. “One of my favorite videos on YouTube, it looks like it’s from the late ’80s or the early ’90s, and it’s this group doing this ‘return to the motherland’ pyramids tour. As soon as they see the pyramids, they’re like, ‘My relatives did that.’”

“I know all black people weren’t pharaohs from Egypt,” she adds. “But I’m fascinated by what compels the myth.”

I was interested in architecture because of how it says so much about class and race and the demographics of this city.

— Lauren Halsey

In his review of the biennial, Times art critic Christopher Knight described Halsey’s prototype as “impressive” — a white cube where humble materials amount to grand things.

The piece also caught the attention of the jury in charge of granting the 2018 Mohn Award, given in conjunction with the Hammer biennial. On Wednesday morning, Halsey is set to be named the recipient of the $100,000 prize for artistic excellence.

“She is someone who exemplifies what the show was,” says Thomas J. Lax, an associate curator at the Museum of Modern Art in New York who served on the jury. “It was a show that was about the possibilities of art in the future and it’s about the here and now.”

He says the jury was taken with how the artist drew from various eras — “the funk traditions of the ’70s and ideas of Afrofuturism” — but extended those ideas forward. Her installation, he says, “doesn’t require the museum to exist. The thing that she is making will exist on Crenshaw Boulevard one day.”

My interview with Halsey took place before the Mohn Award was announced. But in a short email in response to the news, she stated: “This award affirms that artists can make work that’s rooted in their community’s concerns and experiences and it will resonate with a broader audience.”

The Crenshaw Boulevard prototype is not the only architectural piece that the artist has on display in Los Angeles right now. Across town, at the Museum of Contemporary Art on Grand Avenue, she has transformed a hallway area in the museum into a psychedelic grotto that also riffs on themes of the mystical.

In it, the museum’s tidy white walls seem to have been reconfigured into a bright cave. Its various crevices are stuffed with signifiers of blackness: a logo for Black ‘n Gold weave hair, black figurines doing aerobics and playing basketball, ankh-laden carpets bearing powerful felines, street signage, brochures and bottles of essential oils that purport to channel the scent of “Oprah’s Money.”

Halsey has taken the white cube and made it whimsically, beguilingly, urgently and magically black.

“She’s one of those people who is much more than just an artist,” says Erin Christovale, a Hammer curator who helped organize the “Made in L.A.” biennial. “She’s an archivist. She’s a funk aficionado. She’s an architect. And she utilizes her art practice as a way to continue the legacy of black cultural production in this city in a really honorable way.”

Halsey grew up in various neighborhoods in South Los Angeles with her mother, a schoolteacher and her father, an accountant. It was from him that she got her interest in the mystical.

“I think I inherited the obsession with ancient Egypt and pharaonic architecture via my father and Parliament-Funkadelic and G-funk, and hearing friends and family freestyle these origin stories about black people,” she says. “That was in my bones.”

For much of her young life, she devoted herself to basketball. Halsey is slender and long-limbed, carrying herself with a low-key grace that is coupled with thoughtful determination. But her senior year of high school — she attended the Los Angeles Center for Enriched Studies, graduating in 2005 — she set basketball aside and began to focus on art.

Making things had always been a part of her life. Her bedroom was even an evolving installation.

“My parents let me go crazy in my room,” she says. “It was, like, covered in foil. It had collages. I collected signs, incense, mix CDs. I collected a lot of hair and things that were related to promise and myth. I like scents and incense and oils and imagining what gets summoned when you burn this or open that.”

“Though I never open them,” she adds. “But I love the titles. They are portals for me into a whole other world.”

She was a world-creator too.

In middle school, her aunt would ask her to help make sets out of cardboard for church plays. Later, in the 12th grade, the same aunt introduced her to Dominique Moody, a Los Angeles artist whose work is inspired by architecture, especially as it pertains to the African American experience.

“She said, ‘Why don’t you take an architecture class?’ ” recalls Halsey. “I was interested in architecture because of how it says so much about class and race and the demographics of this city. I wanted my architecture to interrupt some of that.”

After high school, she studied at El Camino College in Torrance, then spent a year at the California College of the Arts in San Francisco, studying architecture — but found it “disappointing.”

She ultimately ended up at the California Institute of the Arts, where she could pursue architecture from the perspective of art. While getting her MFA at Yale University, she turned her studio into an architectonic sculpture — one reminiscent of her winding, object-stuffed grotto on view at MOCA.

“I accumulated installation on top of installation,” she says. “It was this labyrinth, this super-funky, DIY free-form, freestyle build structure that soon became a social space for some of my friends in the program or DJs in the neighborhood.”

Throughout all of these experiences, Halsey has remained a dedicated chronicler of Los Angeles.

During her long bus rides to CalArts as an undergraduate, she would record street sounds, and snap pictures of architecture, road signs and the random drawings and funny expressions etched into wet concrete or the dusty windshield of a car. She is interested, she says, “in the sign of the hand — whether it’s in a braiding style, whether it’s in a gorgeous sign painting style, a pattern.”

As development has seized parts of South Los Angeles — in particular the area around Crenshaw Boulevard near Exposition and Martin Luther King Jr. boulevards — Halsey has felt an urgency to pay tribute to and record the presence of black Los Angeles.

She began work on the “Crenshaw District Hieroglyphic Project” in earnest four years ago during a residency at the Studio Museum in Harlem, when she created a series of carved panels that drew inspiration from Egyptian architecture. In an essay in Artillery magazine in 2016, fellow artist Todd Gray said he was “stupefied” by her work when he first laid eyes on it.

It was, he writes, “genuinely a new experience, challenging my notion of visual and spatial aesthetics.”

In addition to her various museum shows, Halsey has, as of late, turned her attention to securing a location for her Crenshaw Boulevard monument. (She hopes to make some announcements related to that in the fall.)

But above all, she wants the project to not only represent South Los Angeles, but embody it too. In all of her work, she engages the participation of artists, friends, colleagues and neighbors. She aims to do the same in the neighborhood where the monument will ultimately reside.

“My work is a constant collaboration with people who live in the neighborhood,” she says. “With the permanent project, it will be that on a larger scale. I’ll tap organizations in the neighborhood to build it with me. It’s not just architecture that’s for us. It’s for us and by us.”

The monument is an ambitious undertaking. But Halsey is already looking beyond it.

“Before I die,” she says pensively, “I want to build my own city block.”

“Made in L.A. 2018”

Where: Hammer Museum, 10899 Wilshire Blvd., Westwood, Los Angeles

When: Through Sept. 2

Info: hammer.ucla.edu

“Lauren Halsey: we still here, there”

Where: Museum of Contemporary Art, 250 S. Grand Ave., downtown Los Angeles,

When: Through Sept. 3

Info: moca.org

ALSO:

Lauren Halsey takes a fantastic voyage in MOCA’s ‘we still here, there’

‘Made in L.A. 2018’: Why the Hammer biennial is the right show for disturbing times

Why Luchita Hurtado at 97 is the hot discovery of the Hammer’s ‘Made in LA’ biennial

Why artist Rafa Esparza led a surreal art parade through the heart of L.A.’s fashion district

Sign up for our weekly Essential Arts & Culture newsletter »

More to Read

The biggest entertainment stories

Get our big stories about Hollywood, film, television, music, arts, culture and more right in your inbox as soon as they publish.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.