After 15 years, a forest, a pig and a giant tongue, Echo Park alternative arts space Machine Project is closing its doors

- Share via

The opening was short and sweet.

In fact, the 2003 debut piece by Kelly Sears at Machine Project, the artist-run space in Echo Park, took all of 10 minutes.

“It was her and this guy, Ian, and they had this 10-minute metal show,” says founder Mark Allen of Sears’ “Sexy Midi.” “They had videos, these animations of wizards and crystals. The doors opened at exactly 10 p.m. and the doors were locked at 10:10 p.m. By 10:21 everyone had to leave.”

Since then, the humble storefront that Allen opened on a lark, after spotting a for-rent sign on the Alvarado Street building, has hosted countless art installations, avant-garde musical events, lectures and wild public performances. Last year’s “Panopticonathon Streetview” by artist Mary Fagot, staged in the building’s windows, used sound, projections and graphics inspired by Bauhaus ballet costumes to turn performance art into a full-blown spectacle for the street.

Machine Project, says Allen, seated amid the detritus of an upcoming posters exhibition, has been “about coalescing large groups of artists who weren’t represented by galleries and who weren’t being shown in museums.”

After 15 years, that is coming to an end. On Jan. 13, the arts nonprofit will host its final event: a wrap party and poster sale, featuring the silkscreen exhibition fliers created over the entire life of the space.

Allen, who teaches at Pomona College (and who ran a pair of informal artist-run spaces in Houston, where he lived before he relocated to L.A.), says it was time to move on.

“I saw this as an exploratory and research project,” he says. “It kind of emerges and shares knowledge and information and then dissolves so that the next thing can emerge.”

One thing is for sure: Machine Project leaves behind a vibrant legacy. Over its existence, the organization collaborated with the Los Angeles County Museum of Art on a series of strange-funny performances and it once organized an architectural tour of L.A. led by artist Cliff Hengst channeling the ghost of Whitney Houston.

“It was this heavily researched architecture tour,” says Allen. “But it was also this heavily researched story about Whitney Houston.”

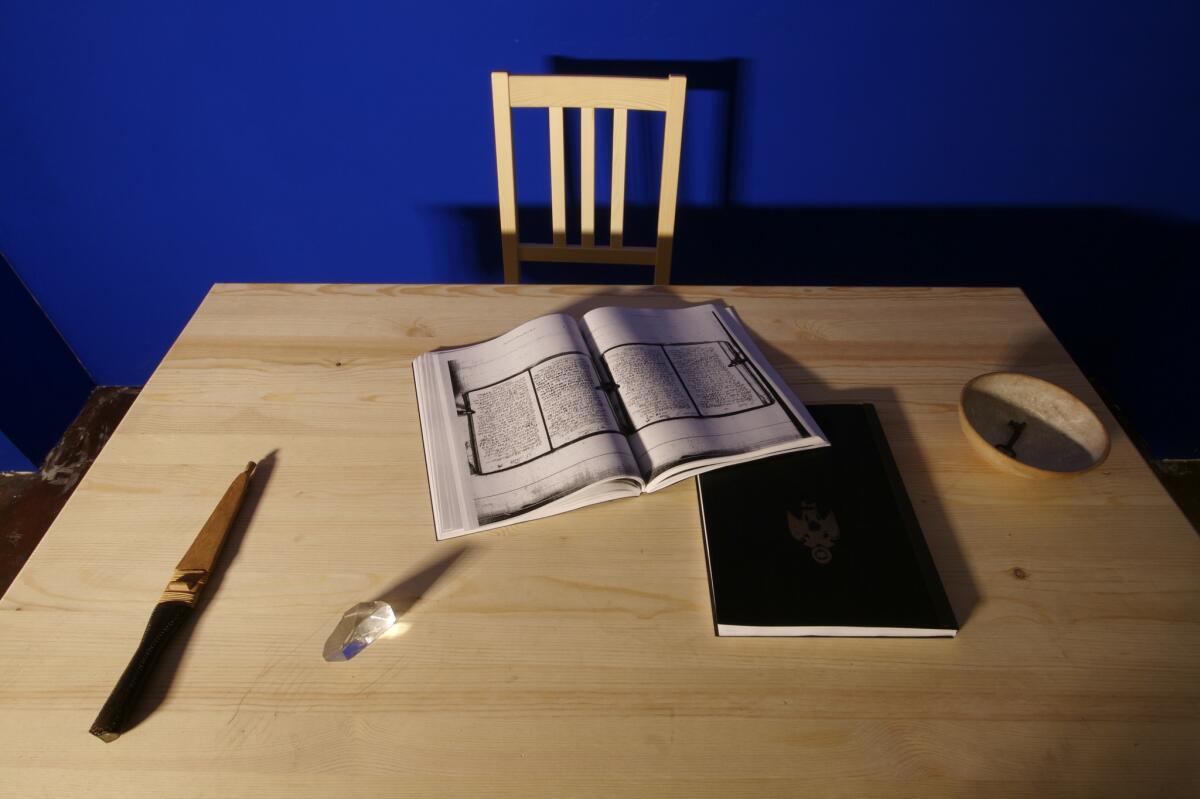

Many of the space’s unusual, often humorous, installations, are gathered in the book “Machine Project: The Platinum Collection,” published last year by Prestel. But Allen took time last week to reminisce about five of his favorite events. As with many things Machine Project, they are a little weird — collectively involving a forest, a pig and a very large tongue.

An artsy TV studio

In 2007, an installation by artist Kamau Patton (then based in San Francisco) took over the space, transforming part of the small storefront into a television studio that was used to record a public access-style talk show that fused esoterica and radical politics. In one bit, in which Patton played every character, a fictional Nation of Islam-type faction chattered about light and energy while a toll-free number flashed on-screen.

The show reflected Machine Project’s commitment to emerging artists — at that point, Patton (who has since staged events at LACMA and New York’s Museum of Modern Art) was fresh out of the master’s program at Stanford University.

“I never saw the point of nonprofits working with artists who are being seen a lot in commercial galleries,” Allen says.

It also launched an ethos of letting one exhibition flow right into the next. A wall built for Patton’s television studio was recycled as a handball court for the next installation.

“I commissioned different artists to make op-art murals on which people would play handball,” says Allen, referring to art that employs optical illusions. “It was just this weird thing where people wandered in and were knocking balls everywhere.

“Instead of seeing an artist in isolation, it’s about seeing them as part of a community and part of an ongoing conversation.”

Forest in a gallery

Two year after Patton’s show, set designers Sara Newey and Christy McCaffrey used tree branches, Styrofoam, wood and other props to transform the Machine Project space into a dense forest.

“I’d met [director] Noah Baumbach and Jennifer Jason Leigh, who were married at the time,” Allen recalls. “They needed a scene in an art gallery for a movie, so I convinced them to pay for it and they would shoot a scene in the gallery. So they funded it and we had this opening that was like a keg party in a forest.”

But “The Forest” was much more than a one-off visual gag. It was a full-on interactive experience.

“We had bird-watching,” Allen says. “We built maple syrup taps into the trees — so we had a pancake breakfast … We met some Sasquatch researcher and they came and gave a talk about Sasquatch. I met this woman who had a pet pig and we set up a photo studio where you could get your children photographed in the forest with the pig.”

In true Machine Project style, all of the material from that installation was employed in the next: Artists Liz Glynn and Nate Page recycled all the Styrofoam and dead tree branches into made-to-order sculptures in a project titled “Machine Project Deforestation Squad.”

A domestic takeover

Over its lifetime, Machine Project staged events at arts institutions such as LACMA (10 hours of performances) and at the Hammer Museum (80 programs that included a series of micro-concerts in a coatroom). One of its more surprising collaborations took place in 2014 at the generally staid Gamble House in Pasadena, the early 20th century Craftsman home that once belonged to David and Mary Gamble, of Procter & Gamble fame.

For that setting, Allen and a group of artists affiliated with Machine Project installed a series of contemporary artworks around the historic home in ways that both highlighted and harmonized with the architecture. This included a secret basement restaurant operated by Bob Dornberger whose menu was inspired by the architecture, and a massive sculpture of a vortex on the front lawn by Patrick Ballard that was also a a puppet. (The latter’s design was inspired by the Gamble family crest.)

Allen says it was an opportunity to reconsider contemporary art — generally shown in pristine white cubes — in a different context, one that was woody and dark.

“I wanted to see what kind of conversations we could have,” he says. “It was really about thinking about how ideas work through time.”

Lady of the lake

Allen says that he frequently tried to play with the idea of duration. In May, he teamed up with experimental vocalist Carmina Escobar for a day-long performance at Echo Park Lake that featured the singer performing on a floating platform as a Oaxacan brass band led a procession along the perimeter.

“I knew I wanted to do something with her on the lake,” says Allen. “She said, ‘I have this crazy idea.’ I said, ‘Tell me about it.’ My favorite thing is when artists have a ridiculous idea and they need someone to say, ‘Yeah, let’s do it.’”

“Fiesta Perpetua,” as the piece was called, ran from sunrise to sunset, and featured the ethereal sight of Escobar singing into large wooden megaphones — delivering notes that fluctuated between the operatic and bird-like. (The artist will reprise the piece on Jan. 13 as part of a performance art festival connected with Pacific Standard Time: LA / LA.)

The work had a “pied piper” aspect to it, Allen says. Spectators followed the band. Paddle boaters on the lake followed Escobar’s floating platform.

“You had all of these different audiences,” Allen says. “It’s all these people following other people around.”

Purple play

If you’d entered Machine Project in October 2014, it would have looked just like any other ramshackle storefront gallery with beat-up walls and an old couch. But if you had taken the tight spiral staircase down to the basement, you might have felt as if you’d slipped into Alice’s rabbit hole.

At the bottom of the staircase, a diminutive theater welcomed viewers, as did playwright Asher Hartman’s “Purple Electric Play (PEP!),” a surreal stage work that told an abstract, nonlinear story about ... well, it’s hard to say.

“I always fail to describe his work, which is why I’m interested in it,” says Allen of Hartman. “It’s ability of language to do something complicated — to produce very complicated affect and to convey meaning in non-literal ways.”

The play employed the campy tools of vaudeville to explore “the relationship between revolution, violence and art,” Allen says. There were elaborate choreographies that included a dancing salad and a giant tongue that swept everyone off the stage.

“PEP!” was one of six plays by Hartman that was staged at Machine Project — some of which spent a year and a half in production before they ever hit a stage. “They are among the most intensive things we have done,” Allen says.

But they provided Machine Project with an opportunity to turn theater on its head — as well as the space itself.

It was a Hartman play that served as the final event at Machine Project this past fall, a work titled “Sorry, Atlantis, Eden’s Achin’ Organ Seeks Revenge,” which explored the nature of power and misogyny in ways both abstract and preposterous. (Imagine a man-baby wielding a blow-up phallus.)

To stage the work, Allen and Hartman ripped the floor off the gallery and then placed it at a steep angle, so that the stage appeared to recede into the ceiling. Actors emerged from and disappeared into holes cut out of the floor. Sometimes they’d let gravity take over and slide down the ramp toward the audience. In various scenes, actor Philip Littell considered the nature of toxic masculinity while decked out in a banana yellow mankini — and nothing else.

“I wanted to end with his play because [Asher’s] been so important to me,” Allen says. “I liked the idea of upending the whole space.”

In many ways, it was the ultimate Machine Project piece: wildly experimental, ridiculously absurd yet dead serious, a reconfiguration of the everyday into something extraordinary and bizarre.

Machine Project Wrap Party & Poster Sale

When: Jan. 13, poster sale 2 to 6 p.m.; party 6 to 9 p.m.

Where: 1200 N. Alvarado St., Echo Park, Los Angeles

Info: machineproject.com

The biggest entertainment stories

Get our big stories about Hollywood, film, television, music, arts, culture and more right in your inbox as soon as they publish.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.