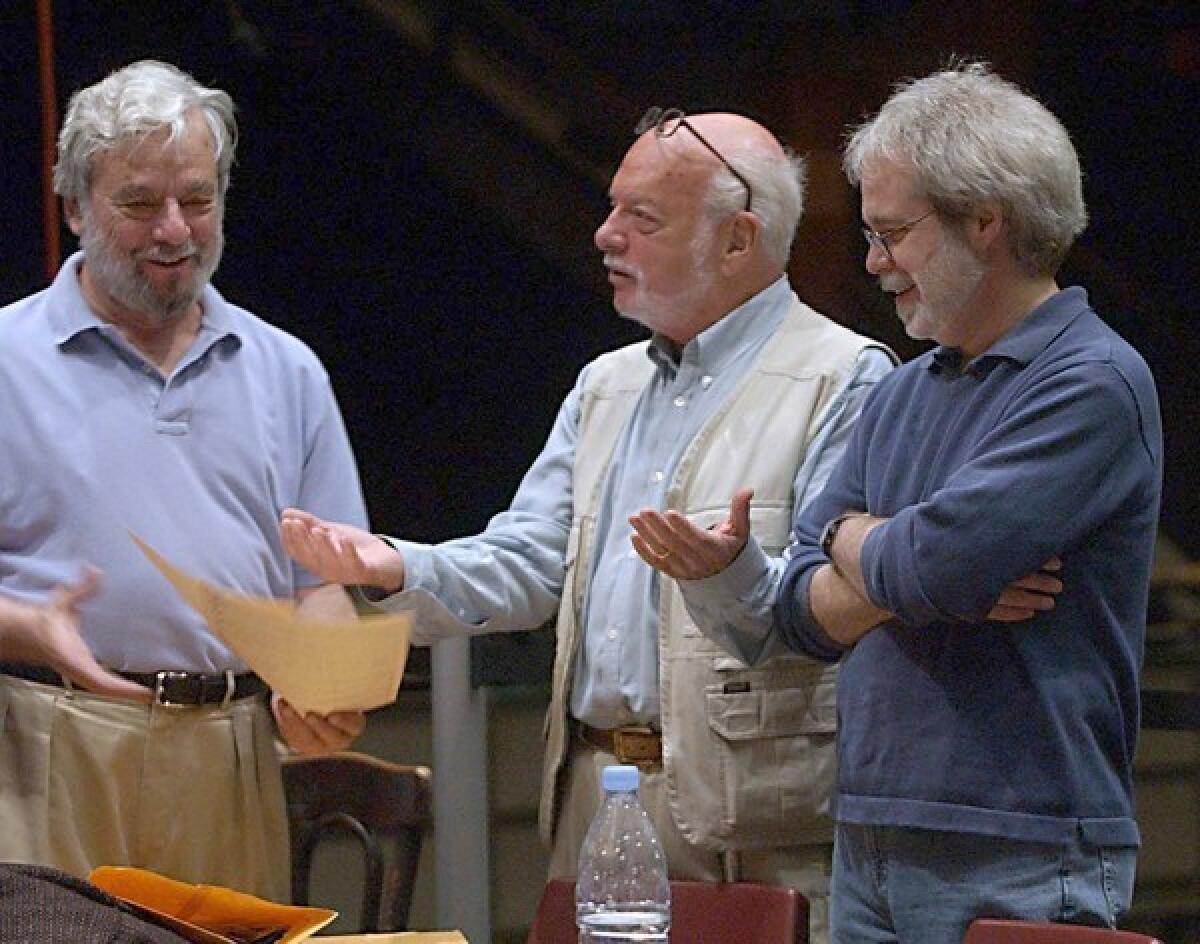

In Sondheim’s company

- Share via

Few people have turned 80 with the fanfare shown Stephen Sondheim, master of the musical theater. There was “Sondheim: The Birthday Concert” at Lincoln Center’s Avery Fisher Hall. The Roundabout Theatre Company in New York will rename its Broadway house the Stephen Sondheim Theatre. Opening Thursday on Broadway is the Roundabout’s “Sondheim on Sondheim,” conceived and directed by the composer-lyricist’s frequent collaborator James Lapine. The show features not just lots of Sondheim songs but lots of Sondheim on-screen talking about those songs and himself. For the occasion, The Times asked several of Sondheim’s collaborators to share their thoughts on the man and his music.

Harold Prince director and producer

Steve and I first met at the opening of [Rodgers & Hammerstein’s] “South Pacific” in 1949. I was 21 and there with the Rodgers family, and he was 19 and there with the Hammersteins. We were introduced, and soon after, we got to be good friends. We had bachelor pads not far from each other, on the Upper East Side, and we saw each other a lot. Sitting at the counter in Walgreen’s, eating BLT sandwiches, we’d talk about what was happening in the theater and how we wanted a place in it. We were probably a little intemperate because we hadn’t yet had to deliver ourselves. You’re not as generous when you’re young as when you’re older and you know how damn hard it is.

We had a number of false starts on shows we were both interested in. Then, in 1956, when Steve told me “West Side Story” lost its producer, [my producing partner] Bobby Griffith and I flew from Boston, where we were on the road with “New Girl in Town,” into New York that Sunday and went over to Lenny Bernstein’s apartment to hear the music. Lenny played his score while Steve stood next to the piano and sang some lyrics. It was wonderful, and we flew back to Boston having agreed to produce it. There were a lot of walkouts, yet you knew every night that it was miraculous and making history.

“A Funny Thing Happened on the Way to the Forum” was the first time Steve wrote both the music and lyrics. Then, in 1970, we did “Company,” and we changed people’s definitions of musicals. We changed taste and what was acceptable. We had 10 amazing years. Every year we had something people liked, show after show -- until “Merrily We Roll Along,” which was so over-publicized and then savaged. We could never get out of that hole that success makes for you. It probably contributed to the end of Steve and my collaboration, but the friendship always survived big time. We’re family.

John Weidman playwright

When Steve and I did “Pacific Overtures” in the mid-’70s, he was still smack in the middle of the Prince-Sondheim run of shows. I had written a straight play that interested Hal Prince, and Hal, whose enthusiasm tends to be contagious, had sort of dragged Steve into the collaboration. Steve first saw it as a play for which he could provide music, and when it was pulled apart and re-imagined, it came to life as a musical.

Steve and I first met to talk about “Assassins” in 1987. I had gone to him with the idea of the Paris Peace Conference of 1919, and Steve asked, ‘What about assassins?’ We started talking about this collection of people, deliberately avoiding a topic sentence and letting the material form and change patterns. We thought that if we looked at these characters together, something they had in common would emerge, and we thought something did.

We talked as much as we could until it became an embarrassment to both of us that we weren’t actually writing anything, at which point Steve went away to do the opening number and I went away to write a draft of the show. We sort of fed off each other’s excitement about the writing, and one of the things I’m proudest of is that in the end, the show feels like it was all written by one person, like it all flows from one pen. “Assassins” is the most satisfying writing and collaborative experience I ever had. It started with me and Steve in a room, and we finished writing it before any third party was involved.

A few years ago, when Steve and I were doing “Road Show,” about the brothers Addison and Wilson Mizner, we wanted to add a song for the Public Theater production. Steve said, “Give me a story.” I go away and write a two-page scene, and the greatest composer and lyricist in the history of the America musical theater turns it into a song.

Paul Gemignani musical director

I worked on every show Steve’s done except for “Company” and “Forum.” About 40 years ago, I was on the road with the musical “Zorba” when musical director [Harold] Hastings called to say he had another job for me. I’d been a drummer since I was 16, and I said, “If it means playing drums, forget it.” He said, “Yes, you’re playing drums, but you must be involved in this show. It has everyone in the theater you will ever need to work with -- Harold Prince, Michael Bennett, Stephen Sondheim.” I wasn’t from that world. I didn’t know who they were. But he said when my contract was up he would fire me if I didn’t take the job, so I did. The show was “Follies,” and I started with it as a drummer, then later got to conduct it on the road. I never went back to drumming.

My son Alex got in the business by auditioning right out of college for the Roundabout’s revival of “Assassins.” The director Joe Mantello kept bringing him back, and after Alex was cast as [President Reagan’s would-be assassin] John Hinckley, I got to call and tell him. I called him up, said, “How are you doing?” and he went on for five minutes about how he screwed it up, how he felt terrible and blah, blah, blah. I waited until his actor insecurity wore out. Then, when he asked why I called, I said, “To say you got the role.”

Alexander Gemignani actor

That was my first Broadway audition, and it was kind of surreal. Since then, I played Addison Mizner in “Road Show,” and I’ve also done some performances as Sweeney Todd in the national tour, plus smaller parts in productions of “Sunday in the Park With George” and “Passion.” It was a touching thing for my family and for me to be part of this new generation of Sondheim performers and to be an actor coming on the scene right when a lot of Steve’s revivals are happening.

Patti LuPone actress

I know Stephen Sondheim better through his music than I know him in life. His lyrics are deeply emotional, passionate and complex, and I think that reveals the man. Look at “Passion”: It’s just wrung out of the heart. He runs the gamut of all the emotions and invented a few himself.

When I was doing Madame Rose in “Gypsy,” one of the first challenges was the lyric, “Have an egg roll, Mr. Goldstone.” There’s always a patter song like “Mr. Goldstone” in his scores. For my first entrance in “Sweeney Todd” as Mrs. Lovett, I had to sing “The Worst Pies in London,” another of those patter songs, and on that one, you’re singing lyrics that everyone knows. These are incredibly intricate melodies and complicated lyrics, and the first time I have to do one, my heart stops until the song is over.

James Lapine playwright and director

Steve doesn’t write songs. He writes monologues. They’re character-based, and they’re site-specific. They have to have a reason to be. It isn’t just because there’s a tune floating around in his head or he’s got a lyric. Some writers have notions for songs and write the songs, and that’s not the way he works. He’s truly a writer of the theater. He’s not a songsmith. He wouldn’t have been a Tin Pan Alley guy.

Steve and I wrote “Sunday in the Park With George,” “Into the Woods” and “Passion,” and he always says that when you collaborate, you really are joined at the hip. He is a very generous collaborator. But he’s smart too. When we were working on “Passion,” I wanted it to be sung-through. We worked on it for a while, then he said, “James, you just don’t want this much music. The ear needs to rest.” I had to learn that the book of a musical doesn’t just set up songs in terms of plot and story but also gives the ear a respite from songs and makes the songs stronger. I always say that people go to musicals to hear the music. They don’t go to hear the book.

I hadn’t worked with Steve in quite a long time when “Sondheim on Sondheim” came about. A few years ago, I saw an English revue called “Opening Doors” that played a few performances in New York, using some voice-over narration from Steve, and I got excited about it. I had done the beginnings of a revue 13 years ago with Barbara Cook at the Roundabout, and I thought, with film technology being what it is, you could bring Steve literally on stage. I told him, “I’d like to give the audience the opportunity to spend time with you, not just your work.” And he said, after he’d thought about it, “I would love to have spent an evening with the Gershwins or with Harold Arlen.”

Barbara Cook singer

I’ve known Steve since the ‘50s, but this is the first time we ever worked on a real show together. I go back to those songs, some of which I’ve sung for 25 years, and I find something new in them all the time. They are like great scenes. When I get inside one of his songs, I feel safe because there is so much material to use. Sometimes when the song ends, I don’t want to come back to reality. I want to stay in the song.

In 2001, I did a concert at Carnegie Hall called “Mostly Sondheim,” which included both songs that Steve wrote and songs that he loves and wishes he had written. He came to a party at my house afterward, and he said, “You won’t believe the song that moved me the most. It was ‘Waiting for the Robert E. Lee.’ ” When I did the show again at Kennedy Center, he told me he cried after “Hard Hearted Hannah.” I said, “ ‘You cried after “Hard Hearted Hannah”?’ ” “Yes,” he said, “I cried because of your joy in singing it.” Can you imagine that? He surprises you all the time.

More to Read

The biggest entertainment stories

Get our big stories about Hollywood, film, television, music, arts, culture and more right in your inbox as soon as they publish.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.