Q&A: Spielberg, Hanks and Rylance talk about the Cold War, geopolitics and ‘Bridge of Spies’

- Share via

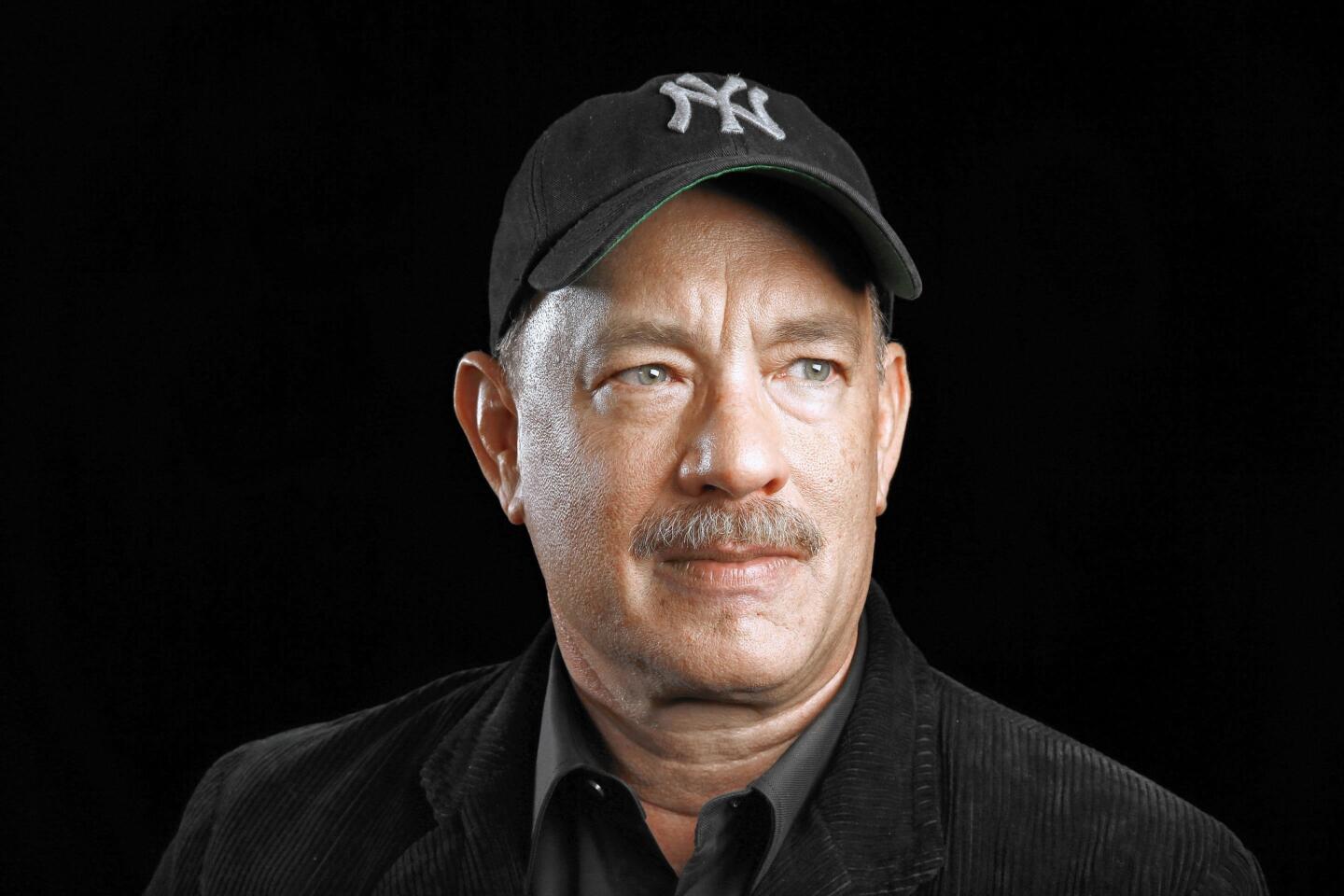

NEW YORK — Steven Spielberg’s latest film, the Cold War drama “Bridge of Spies,” which opens Oct. 16, unites him with his “Saving Private Ryan” star, Tom Hanks, and introduces a new actor to his stable. Englishman Mark Rylance, who is best known for his stage work and performance as Thomas Cromwell in the BBC miniseries “Wolf Hall,” will also star in Spielberg’s next film, “The BFG.”

In the true story, from a script by Matt Charman and Joel and Ethan Coen, Hanks plays Brooklyn insurance lawyer James Donovan, who was assigned the thankless task of defending Soviet spy Rudolf Abel (Rylance) in the 1950s and became ensnared in a larger geopolitical plot. In some ways, this focus on lawyering and the art of deal-making feels like a companion piece to the director’s study of messy democracy in “Lincoln.”

SIGN UP for the free Indie Focus movies newsletter >>

During the New York Film Festival earlier this month, Spielberg, Hanks and Rylance spoke with The Times about the parallels between Cold War paranoia and contemporary fears, the shifting notions of heroism on screen and the impact of seismic changes to their business.

What was your experience of the Cold War as a child?

Tom Hanks: Every day we studied it. Every day it was in the papers. There was this concept that World War III was inevitable and it was going to be us versus them. It was in “Twilight Zone” episodes, “Star Trek.” There was always this dark cloud that was slowly coming toward us.

There was an earlier attempt to tell this story.

Steven Spielberg: In 1964 or ‘65, when it was better known and closer to the incident. Gregory Peck knew about this story and had approached MGM and asked them to finance a screenplay about the spy swap, and then Peck sent the script to Alec Guinness and got him to agree to play Abel. MGM decided not to go ahead and make the picture because of the tension.

Mark, you’re playing a Soviet spy. Did you think of him as a good guy or a bad guy?

Mark Rylance: I try to avoid judging the characters I play, even an out-and-out bad guy like Richard III. I just try to figure out what they need and play that. I don’t know exactly what he was doing. I didn’t set out to make him charming. I think being charming was the last thing he’d be concerned about. I was struck that when he was a painter he didn’t just put up a front of being a painter, he tried to make himself a better painter. He had an interest in the craft and the art. He had a culture to him.

You could have made a version of this film focused on the spy craft, but instead you chose to focus on an attorney. How come?

Spielberg: The core relationship between James Donovan and Rudolf Abel was for me the way into the story, not the events of the Cold War, not the spy craft of opening quarters and finding the parchment inside. That was fun to do in the one scene we actually shot. But for me it was a man standing on his principles to defend an enemy of everything we deemed sacred.

He was being given a chance to demonstrate the American justice system at a time when anything associated with communism and the red menace was despicable to everyday Americans.... Donovan wanted to show that everybody, even an alien caught breaking the law in this country, deserves the same defense an American would get.

In entertainment we’re awash in antiheroes right now, but Donovan is an unqualified good man. Tom, is there a unique challenge in playing someone that straight?

Hanks: Insurance lawyers all over the country will thank you for that summation.

Two things about Donovan made me, as a selfish actor, want to lunge for him. There is the clarity of the ideology. At some point, great cinema is made out of a character saying, “Well, a man’s gotta do what a man’s gotta do.” Great storytelling rarely is about cowardice. It’s usually about the opposite of that.

The other side of it is his profound confidence in his own skill in order to go into a negotiation and get what he wants. He’s a profoundly skilled negotiator. Americana is so cheap and easy to slap into any movie. You can always put circles on a piece of metal with a star in the middle and you’re Captain America and everybody knows what you stand for, not to take anything away from Captain America, he’s a fine superhero. But it’s when the audience is asking, “Well, what would I do?” — it becomes a question of when do we define ourselves as Americans? At very specific points, as it turns out.

Watch the first trailer for “Bridge of Spies.”

Rylance: You do as an actor something I’m not sure any English actors do. When I watch Tom I’m able to feel, “What would I do?” I think because of the English class system, we do characters and crafty things but I don’t know many English actors that will play a normal person that makes the audience ask, “Would I have the guts to do that?” It’s so simple and straight. It’s so accessible.

I thought it came down to the film industry being in the West in America and you’re open to such extraordinary landscape and forces of nature so you subconsciously measure yourself as American actors to the expression of nature here. In Europe we have Chartres Cathedral or St. Paul’s. You have the Grand Canyon.

Spielberg: The way I look at somebody, and if the person earns the title “hero,” it’s going to be after a lot of hard work, a lot of proof. What I always look for in movies is, who can lead me through the story? Who am I willing to follow? In this particular story, we purposely made him a little off-putting in the first scene. When I read that in the Coen brothers’ script, my first question was, “Am I gonna follow that guy anywhere?” As the character evolves I absolutely do want to follow him, but I didn’t want to follow him out of the gate. This allows the audience to choose to follow him.

Rylance: I remember it taking me 100 performances of Hamlet before I had the confidence not to put all my effort in the first scene into convincing the audience that I could actually play Hamlet. He goes from a prince to a king. He’s petulant, he’s rude to his mother and father. He mustn’t be the king otherwise there isn’t an arc. But when you’re a young actor as I was and you’re not famous for anything you want to try and show them all you’re a king in the first scene.

Were you struck by parallels between this story and contemporary events as you were making the film?

Spielberg: They were unavoidable. Today there’s a frosty relationship between Vladimir Putin and the Obama administration and I assume whoever the next administration is going to be. While we were making the movie, Putin was directly or indirectly, however you want to interpret history, invading Crimea, with missions deeper into Ukraine. And then in recent headlines coming into Syria to backstop [President Bashar] Assad. I hear those Soviet sabers rattling in the scabbards.

And today with the missions the drones and U2s perform, the fact that there’s more spying going on today than in the history of civilization, there’s all these cyber-attacks and hackers raid websites for the sport of it. It’s eyeball to eyeball without knowing who owns the eyes.

I found the story very resonant, trying to avoid the easy reaction of identifying an enemy and imagining we’ll end the situation by killing that enemy.

— Mark Rylance

Rylance: What we’re subjected to as citizens, the ability to watch people be beheaded. There’s such a bigger impulse to determine that a certain set of human beings are the enemy and should just be wiped out. People don’t just do things for no reason. The things you see on the Internet and in the news, it’s compelling you to think that people aren’t human beings. Donovan breaks down that boundary of, my guy, our guy. In that way I found the story very resonant, trying to avoid the easy reaction of identifying an enemy and imagining we’ll end the situation by killing that enemy.

In the film you show how public opinion was stacked against Donovan for defending a spy. If we had had Facebook and Twitter at this time, what would have happened to him?

Hanks: He’d have his own Twitter page. I think there is sport to be made and coin as well by the swift rush to judgment. It’s mind-blowing to see how fast somebody’s life can be upended. You go from the extreme of somebody who might have made a joke no one understood was a joke, like the physicist who said it’s hard to work with women because you fall in love with them. That wasn’t policy. He was making humorous remarks at a dinner, the likes of which I make all the time. Then you have the guy who killed Cecil the Lion. Both of those peoples’ lives were torn apart in about 48 hours.

Spielberg: I think Donovan’s family would have suffered many worse slings and arrows had there been social media at that time. The people who would have taken the hits would have been Donovan’s wife and three kids.

Movies like this used to be the bread and butter of the film industry. Increasingly they’re made outside the studio system. What’s the impact of that? [“Bridge of Spies” was co-financed by DreamWorks and Fox in association with Participant Media and will be distributed in the U.S. by Disney’s Touchstone Pictures label.]

Hanks: If you’re just searching out for great stories that are about grown-ups, which is what all movies used to be, well guess what, you’re going to watch TV now rather than go to the movies. You’re going to have just as many options of stories about grown-ups, it’s just a different venue. The crossover for artists — [Mark’s] in “Wolf Hall,” which is a TV phenomenon right now. The only difference is you’re watching it at home whenever you damn well please instead of going to a cinema at 7:10 on a Tuesday night.

The economic aspect of it in the movie business has changed forever. Sequels and tent-poles and blah blah blah. Well then don’t go. Stay home and check out the stuff you have on your own DVR and you will see some of the greatest work that’s ever been committed to film.

Rylance: My daughter is a film student and I offered to buy her a television. She said no I don’t want that, I just want a little projector, and she would download whatever she wanted to watch. When we go on holiday we take a projector, a laptop and a sheet to project it on.

Hanks: My kids only go to motion pictures for social experience.

Rylance: For kissing.

Hanks: We declared who we were by the movies we paid to go and see. That was an artistic creed we were living by. It’s not that way anymore.

Steven, how did you feel seeing “Jurassic World,” which you executive produced, perform as well as it did at the box office this summer?

Spielberg: We were just counting on a level of business that would give Universal the encouragement to renew the franchise.... But what we received instead was such an overwhelming surprise. The film is now third behind “Avatar” and “Titanic,” soon to be fourth behind “Star Wars: The Force Awakens,” which I’m happy to concede to right now.

Your distribution deal with Disney will be up after your next film, “The BFG” [short for “Big Friendly Giant,” based on the children’s book by Roald Dahl]. You still have your offices on the Universal lot. Will you return to Universal?

Spielberg: I hope so. I’ve been living there since 1967, so it’s been my ancestral home. I would love to officially come home again.

More to Read

Only good movies

Get the Indie Focus newsletter, Mark Olsen's weekly guide to the world of cinema.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.