A look back at the blaxploitation era through 2018 eyes

- Share via

With the massive success of “Black Panther” and “Get Out” — and even the raunchy comedy “Girls Trip” — Hollywood is experiencing a renaissance in black film. Stars from Chadwick Boseman to Tiffany Haddish and directors from Jordan Peele to Ava DuVernay are enjoying an unprecedented mix of box office supremacy and cultural significance.

But Stephane Dunn, author of “‘Baad Bitches’ and Sassy Supermamas: Black Power Action Films,” notes the industry has been here, at least in some sense, before.

Just look at “the diversity of the moment of the late ’60s to late ’70s,” she said, pointing to films including Gordon Parks’ “The Learning Tree,” the Oscar-nominated “Sounder” and “Lady Sings the Blues” and Charles Burnett’s “Killer of Sheep,” which all premiered during that period.

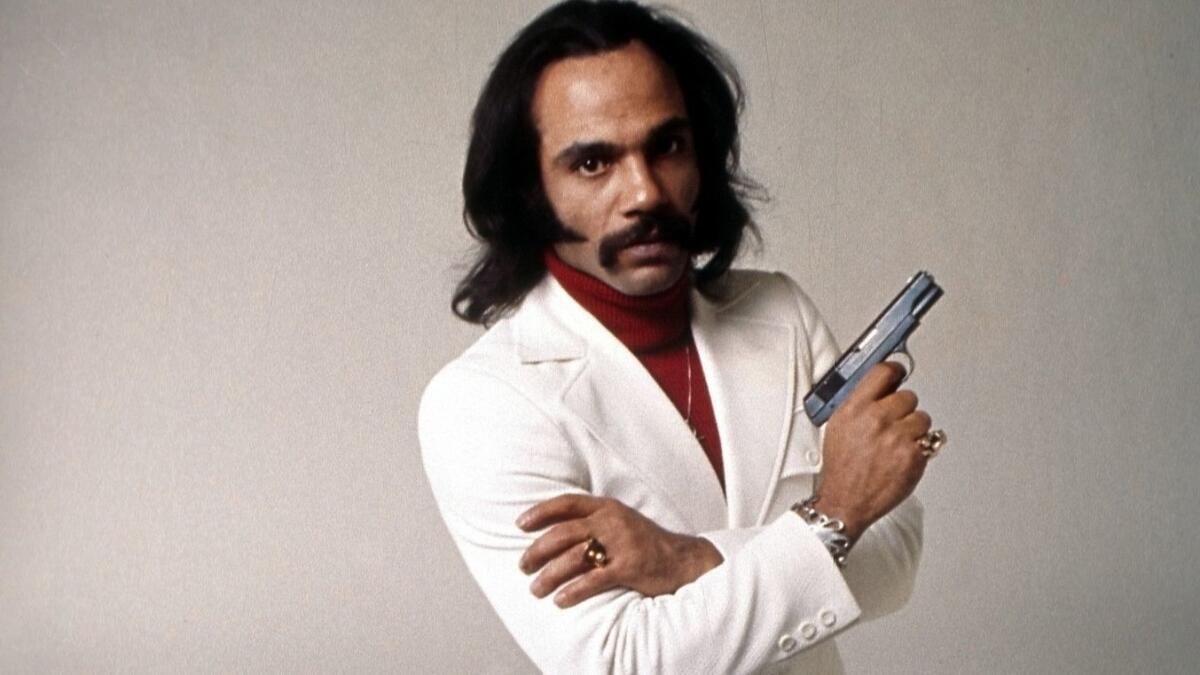

And occupying theaters at the same time were a string of flashy and hugely profitable genre films, indie and studio-produced B-pictures including “Shaft,” “Sweet Sweetback’s Baadasssss Song” and “The Mack,” that captured a form of black life that hadn’t been seen before on screen.

Eventually placed under the umbrella of “blaxploitation,” these films developed surprising cult-like audiences full of black folks with “mad love” for the characters, Dunn said, selling out picture shows nationwide and employing black actors for years to come.

Director X brings blaxploitation classic ‘Super Fly’ into 2018 »

Amid its current reboot and remake craze, it’s no surprise that Hollywood is looking at a number of the era’s films for material. The first of which, “Superfly,” bows June 13. The reimagination of the 1972 picture of the same name stars Trevor Jackson (“Grown-ish”) in the titular role and represents the feature directorial debut of music video helmer Director X. Updated versions of “Shaft,” “Cleopatra Jones” and “Foxy Brown” are also on tap.

But in a new post-“Black Panther” world, audience response ahead of these projects’ release, particularly from black moviegoers, is a mixed bag of elation and concern. Considering what ultimately became of the blaxploitation era — how Hollywood trafficked in arguably unsavory depictions of black life for a number of years and then regressed in terms of black images and stories when the genre was no longer “bankable” — it’s no surprise.

A change in Hollywood

Prior to the early 1970s, representation in Hollywood for black performers was limited, to say the least. The roles most often involved being maids or servants. Even in the rare cases in which characters had some semblance of agency, they were usually alone in a sea of white faces and always remained safely subservient.

Note that before 1970, only six black actors had been nominated for an Academy Award, and only two had won: Hattie McDaniel in 1940 for her supporting role as Mammy in the Civil War epic “Gone With the Wind” and Sidney Poitier in 1964 for his lead role as a traveling carpenter who helps a group of nuns in “Lilies of the Field.”

And it’s not as if the academy was simply ignoring a lot of contenders. Poitier loomed large as the first black bona-fide movie star enjoyed by white and black audiences alike.

Then came Melvin Van Peebles’ independently produced “Sweet Sweetback’s Baadasssss Song” in 1971. The low-budget production, about a black male sex worker on the run from police after saving a Black Panther from and killing racist cops in which Peebles starred, ushered in a heretofore unseen era of American cinema.

While most black men on screen in similar predicaments with the law ultimately met their demise, Sweetback survived, escaping to Mexico. He was, as Times critic Kevin Thomas once wrote, “a symbol of defiance of mythical proportions.”

“Melvin Van Peebles grabbed that narrative and showed a different side of American life, pimps and prostitutes, while pushing back against the black respectability,” said film critic Rebecca Theodore-Vachon. “He was pushing back against Hollywood’s expectation of black people and their thoughts on how we act.”

And audiences, who had become used to asexual, Poitier-type characters, eagerly accepted the alternative viewpoint. The picture grossed a then-astonishing $4 million and is credited as being one of the first to incorporate Black Power ideology. It was even heralded by Huey P. Newton, co-founder of the Black Panther Party, as “the first truly revolutionary black film made.”

Two months later, the studio-produced “Shaft,” which starred Richard Roundtree and went on to land Isaac Hayes an Oscar for original song, premiered. It grossed $12 million, a huge boon for the then-struggling MGM, and the floodgates to countless pictures made for black audiences, starring black actors, sometimes written and directed by black talent, were open.

“You go from virtually no representation to all these blaxploitation movies in the span of a few short years and I don’t know if people at the time knew enough to fully understand and appreciate what was going on,” said Todd Boyd, a professor at USC’s School of Cinematic Arts, rambling off some of the pictures that came within the next two years: “Cleopatra Jones,” “The Mack,” “Blacula,” “Trouble Man” and “Coffy.”

PHOTOS: 11 blaxploitation movies that helped define the genre »

Despite the financial success of these early films, criticism ran rampant. Boyd highlights Lerone Bennett Jr.’s Ebony magazine article titled “The Emancipation Orgasm: Sweetback in Wonderland” in which Bennett accused the film of romanticizing poverty and misery.

Bennett asserted that “‘Sweetback’ was neither revolutionary nor black because it presents the spectator with sterile daydreams and a superhero who is ahistorical, selfishly individualist with no revolutionary program, who acts out of panic and desperation.”

And he noted that though Sweetback saves himself from sticky situations using his sexual prowess — hence “emancipation orgasms” — and can be seen as a representation of sexual empowerment, “it is necessary to say frankly that nobody ever [sexed] his way to freedom.”

“And it is mischievous and reactionary finally for anyone to suggest to black people in 1971 that they are going to be able to screw their way across the Red Sea.”

A year later, the term “blaxploitation” — a combination of “black” and “exploitation” — would be coined by Junius Griffin, then president of the Beverly Hills-Hollywood branch of the NAACP, ahead of the “Super Fly” release. In an August 1972 Hollywood Reporter article titled “NAACP Takes Militant Stand on Black Exploitation Films,” Griffin said the genre was “proliferating offenses” to the black community in its perpetuation of stereotypical characters often involved in criminal activity.

“The transformation from the stereotyped Stepin’ Fetchit to Super Nigger on the screen is just another form of cultural genocide,” he said, as quoted in film historian Ed Guerrero’s “Framing Blackness: The African American Image in Film.”

Boyd understands such criticisms of the era. It’s the classic debate of respectability politics and responses to such productions were often divided along class lines.

“There’s always been this pushback from some people who find these images troubling, problematic, regressive, and others who see them as empowering or, if nothing else, entertaining,” he said. “It depends on where you come down on those lines of respectability.”

Still, Boyd continued, “the images were transformative because they did have this anti-establishment approach and were in a lot of cases about consciousness and politics.”

The idea was that these movies were giving voices to people that didn’t have a voice. They became, in a way, figures that were heroic to regular people.

— Todd Boyd

“The idea was that these movies were giving voices to people that didn’t have a voice. They became, in a way, figures that were heroic to regular people.”

He noted how in the original “Super Fly,” the main character Priest is “an anti-gangster gangster” — a cocaine dealer who’s actually trying to move beyond a life of crime and is able to hold white cops accountable.

“This was really empowering to audiences because you had a black character who not only got the opportunity to tell off ‘the man’ and speak truth to power, but he did it with style,” he said. “It was cool and had a flash to it. It was what cinema was supposed to be. It’s what people would now call ‘woke.’”

Dunn, who’s also director of the Cinema, Television and Emerging Media Studies program at Morehouse College, agreed. She called any rush to dismiss blaxploitation films and the era “a mistake.”

“I think we need not reject those films all out,” she said, noting that the devotion the pictures inspire “isn’t about them being perfect or unproblematic. There is a mad love even though there is a negotiation of the problematic politics of it.”

She elaborated on the gender politics, for example, in some beloved female-led blaxploitation titles.

“Black women did not love seeing Pam Grier in ‘Foxy Brown’ being raped, or groveling on the floor in ‘Coffy.’ We didn’t enjoy that, but what we loved about these movies was that the black hero or heroine wins at the end. They’re the last man or woman standing and kicked ass along the way. There was both psychic escapism and fulfillment in that.

“I don’t dismiss them as mere trash,” she continued. “They are worth our critical eye and thoughts. If they were nothing, just B-grade action films, why do we keep coming back to them?”

An enduring impact

Though the formal blaxploitation era faded away by the ’80s , the ethnic subgenre — which spans genres itself — has continued to rear its head decades after.

Director Quentin Tarantino counts blaxploitation as a foundational inspiration in many of his works, including “Jackie Brown” — which was essentially conceived as a tribute to Grier — as well as “Kill Bill Vol. 1” and “Django Unchained.”

The 2002 comedies “Undercover Brother” and “Austin Powers in Goldmember” both spoofed the genre in an affectionate way, and blaxploitation retains a lasting impact on hip-hop artists like Snoop Dogg, whose persona appears straight out of films like “The Mack” and “Willie Dynamite.”

Next up, Spike Lee’s “BlacKkKlansman,” which recently won a top prize at the Cannes Film Festival and opens in August, incorporates elements of blaxploitation in telling a ’70s-set true story.

Spike Lee hopes ‘BlacKkKlansman’ is a wake-up call for the Trump era »

The latest “Shaft,” which features Roundtree, Samuel L. Jackson (who starred in a previous “Shaft” revival in 2000), Jessie T. Usher, Alexandra Shipp and Regina Hall, is slated for a June 2019 release while “Underground” co-creator Misha Green was hired to reboot “Cleopatra Jones” for Warner Bros. and Meagan Good is developing a “Foxy Brown” series at Hulu.

One thing that wasn’t present in the ’70s that these reboots will have to contend with is social media — and a moviegoing audience ready and willing to vocalize discontent with particular narratives. The 2018 “Superfly” has already faced concern online similar to what critics of yesteryear asserted.

For example, Theodore-Vachon, who goes by @FilmFatale_NYC on Twitter, said that when she saw the “Superfly” trailer, “the first thing that caught my eye was ‘where are the women?’ because I don’t want to just see myself as the love interest or wife.

“I don’t dismiss narratives about drug dealers and prostitutes. My question is are you making these characters complex and three-dimensional in the writing and acting? Is it saying anything new? If you are going to reboot or remake and modernize it, what are you contributing to the conversation?”

Still, despite how any attempts to revive blaxploitation titles may be received, Dunn believes the ongoing conversation they inspire reveals a larger industry issue.

“The fact that [blaxploitation films] remain so much the object of cultural affection, especially black cultural love, speaks to the fact that there has been a gap in Hollywood representation,” she said, “and that gap is still there in representing us large and fantastical in American action cinema.

“We have not traditionally been allowed to be stars and badasses. They’ve rendered us inferior and subordinate. So it’s important to suggest that as we see ‘Black Panther’ make waves, one of the reasons it’s doing so well is because it entered into what has been a vacuum. It has reawakened our whole hope about having more black badasses on screen.

“Because there hasn’t been another era since blaxploitation that has.”

Get your life! Follow me on Twitter (@TrevellAnderson) or email me: [email protected].

More to Read

Only good movies

Get the Indie Focus newsletter, Mark Olsen's weekly guide to the world of cinema.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.