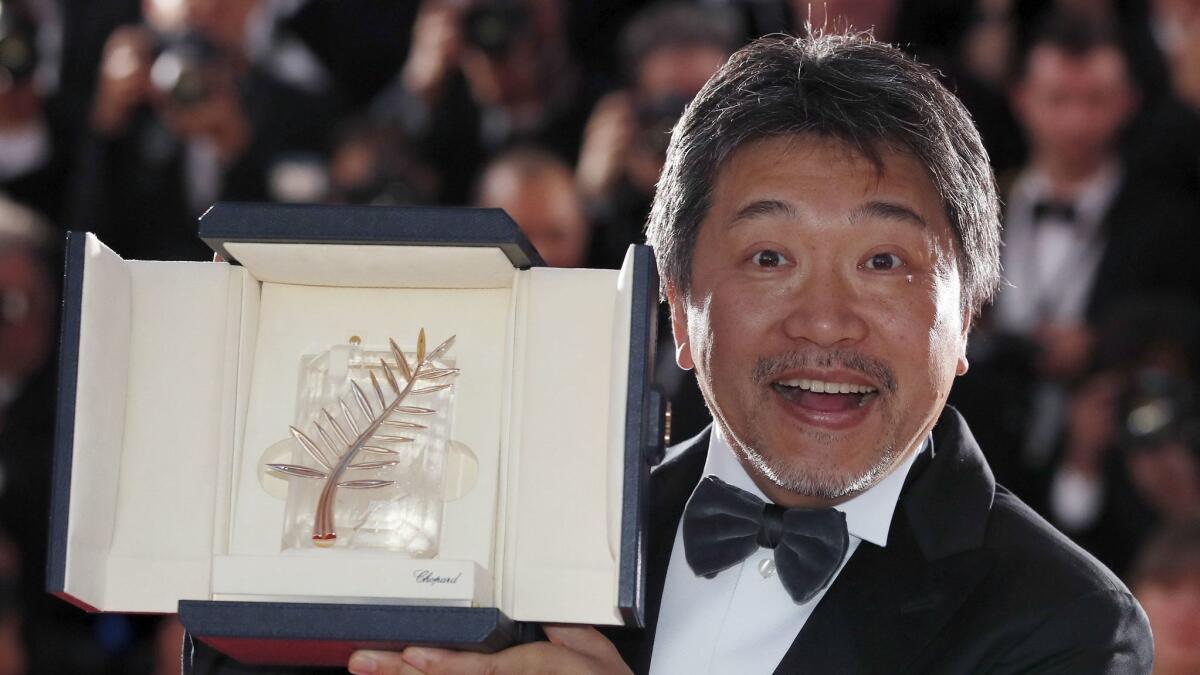

Hirokazu Kore-eda carries on through success and sadness with the release of his Palme d’Or winner, ‘Shoplifters’

- Share via

Sorrow and joy go inextricably hand-in-hand in the movies of Hirokazu Kore-eda, the beloved Japanese writer and director of such intimate, finely tuned family dramas as “Like Father, Like Son” (2014) and “After the Storm” (2017). So it should come as no surprise that the triumphant reception for “Shoplifters,” his quietly shattering new movie about a family caught up in poverty and petty thievery in modern-day Tokyo, has been tinged with sadness.

Since it won the prestigious Palme d’Or at the Cannes Film Festival in May, besting high-profile contenders including “BlacKkKlansman” and “Cold War,” “Shoplifters” has become one of the most critically and commercially successful pictures of the 56-year-old Kore-eda’s career. Set to open Friday in select theaters, the movie has already grossed more than $50 million worldwide and ranks as the director’s biggest Japanese box-office hit.

But the months since the movie’s international release have brought their own heartache, and not merely due to the story’s piercing and perpetually relevant subject matter. It features one of the final screen performances of the veteran Japanese actress Kirin Kiki, who died of cancer in September at age 75. She had previously appeared in Kore-eda’s “Still Walking” (2009) and “After the Storm.”

“Over the years it became much more than just a relationship between a director and an actress, but a partnership in creation,” Kore-eda says of his collaboration with Kiki, speaking through an interpreter. “Her presence was a very important presence for me.”

Kore-eda is sitting down for lunch at the London West Hollywood, where he has been busy promoting “Shoplifters,” which will represent Japan in the Academy Awards race for foreign-language film. He has taken some time off from shooting in Paris, the setting of his next film, “La Vérité” (The Truth), starring Juliette Binoche, Ethan Hawke and Catherine Deneuve; it will be the director’s first picture set outside Japan.

But for all the excitement and upheaval of the past several months (“I’ve been living in Paris for four months now, and I still do not understand one word of French”), Kore-eda seems entirely at ease, as gentle, reflective and approachable as any of his movies.

This remains the case even when the conversation turns toward Kiki. In “Shoplifters,” she plays one of six individuals — four adults and two young children — who appear, at first glance, to be an ordinary family living together in close quarters. But from the opening scene in which one of the kids, Shota (Jyo Kairi), steals food from a neighborhood supermarket while his male guardian, Osamu (Lily Franky), keeps a lookout, it’s clear that there is nothing simple or straightforward about this arrangement.

“Shoplifters” is thus Kore-eda’s latest portrait of a decidedly nontraditional family, a theme that he has previously pursued in movies like the bittersweet 2016 comedy “Our Little Sister,” about three sisters who adopt their younger half-sibling, and the bleak 2004 drama “Nobody Knows,” based on the 1988 account of a mother who abandoned her young children in an apartment for months.

“Shoplifters” isn’t quite so harrowing; its parental figures are irresponsible but not neglectful. But its story was similarly inspired by real-life headlines in Japan, namely reports of people committing pension fraud and parents using their children to shoplift.

“In the very beginning I started thinking, ‘What would it be like to create a family that is not connected through blood relations?’” Kore-eda says. His conclusion was simple: “I connected them through crime.”

The resulting film, while not exactly a thriller, is nonetheless replete with mystery and surprise. Kore-eda’s script, following each character in turn, sketches in every detail of a surprisingly functional yet ultimately untenable domestic scenario. Amid the family’s day-to-day struggle to survive, the movie gradually answers our questions about how these individuals came to know each other and what their immediate and long-term motivations might be.

The other characters include Osamu’s romantic partner, Nobuyo (Sakura Andô), and another young woman (Mayu Matsuoka) who seems to go by two or three different aliases. Several scenes observe all six central characters in their cramped, squalid quarters, a carefully furnished set that Kore-eda’s camera turns into its own self-enclosed world.

“I asked the art department two things: I want it to be three times dirtier than ever before, and three times more cluttered than ever before,” Kore-eda says, adding, “Because I understand that poverty is not a lack of things.”

Kore-eda says he relied heavily on his frequent collaborator Franky, who previously appeared in “Like Father, Like Son,” “Our Little Sister” and “After the Storm,” in order to achieve the right mood and rhythm on set. That proved especially helpful with putting the child actors, Kairi and the quietly heartbreaking Miyu Sasaki, at ease.

“Lily Franky understands what I want from a particular scene probably before I do. We are so strongly connected that I call him my on-screen director,” the director says.

While Franky agrees that he and Kore-eda share a common vision, he downplays his own role in the director’s process, which he describes as both meticulously thought through and accommodating of what his actors bring to the material.

“His process is so gentle,” Franky says in an email interview, noting that he and his fellow actors do their best work “by adjusting ourselves to Kore-eda’s atmosphere and breath.”

“Kore-eda is the only one who knows what is correct for the film. Though he makes an initial outline in advance, he often changes and adds dialogue, depending on how people go.”

Although Kore-eda’s films are prized for their care and craftsmanship, he himself is regarded as something of a workhorse, the kind of filmmaker who ends one production only to promptly begin or resume work on another. This year has already seen the U.S. release of Kore-eda’s “The Third Murder,” a talky serial-killer courtroom drama that drew mixed reviews.

Following soon after “The Third Murder,” “Shoplifters” was immediately greeted as not just a return to form but one of the director’s finest films. Still, its reception abroad has not been without backlash or controversy.

After his Palme d’Or win, Kore-eda declined an official commendation from the Japanese government, drawing criticism in some quarters. Dryly noting that no one would ever take, say, George Clooney to task for turning down an award on principle, the director cites past incidents of governments manipulating movies for their own propagandistic purposes. He also points out that this particular commendation, unlike a prize given by a festival jury, had no clear criteria behind it.

“I feel that there’s no standards,” he says. “The relationship between film and government needs to be a good distance apart. That’s important to me.”

Despite the movie’s record-breaking commercial success, some have rejected it for daring to show empathy with characters who break the law. Kore-eda says he is saddened but not surprised by these reactions.

“When you look at a criminal, you also have to look at what society created that criminal,” he says. “What I’m finding in Japan is that this concept is disappearing, and more and more the emphasis is on the individual’s fault. And I feel that is a very warped, and I emphasize warped, human view of life and society.

“Do you have the right to say this group is not a family?” he asks. “That was the question I’m throwing at the audience. Or to put it another way: Is your family connected more and better than this family?”

More to Read

Only good movies

Get the Indie Focus newsletter, Mark Olsen's weekly guide to the world of cinema.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.