From the Archives: Garry Marshall knew what he wanted when he built his Burbank theater

- Share via

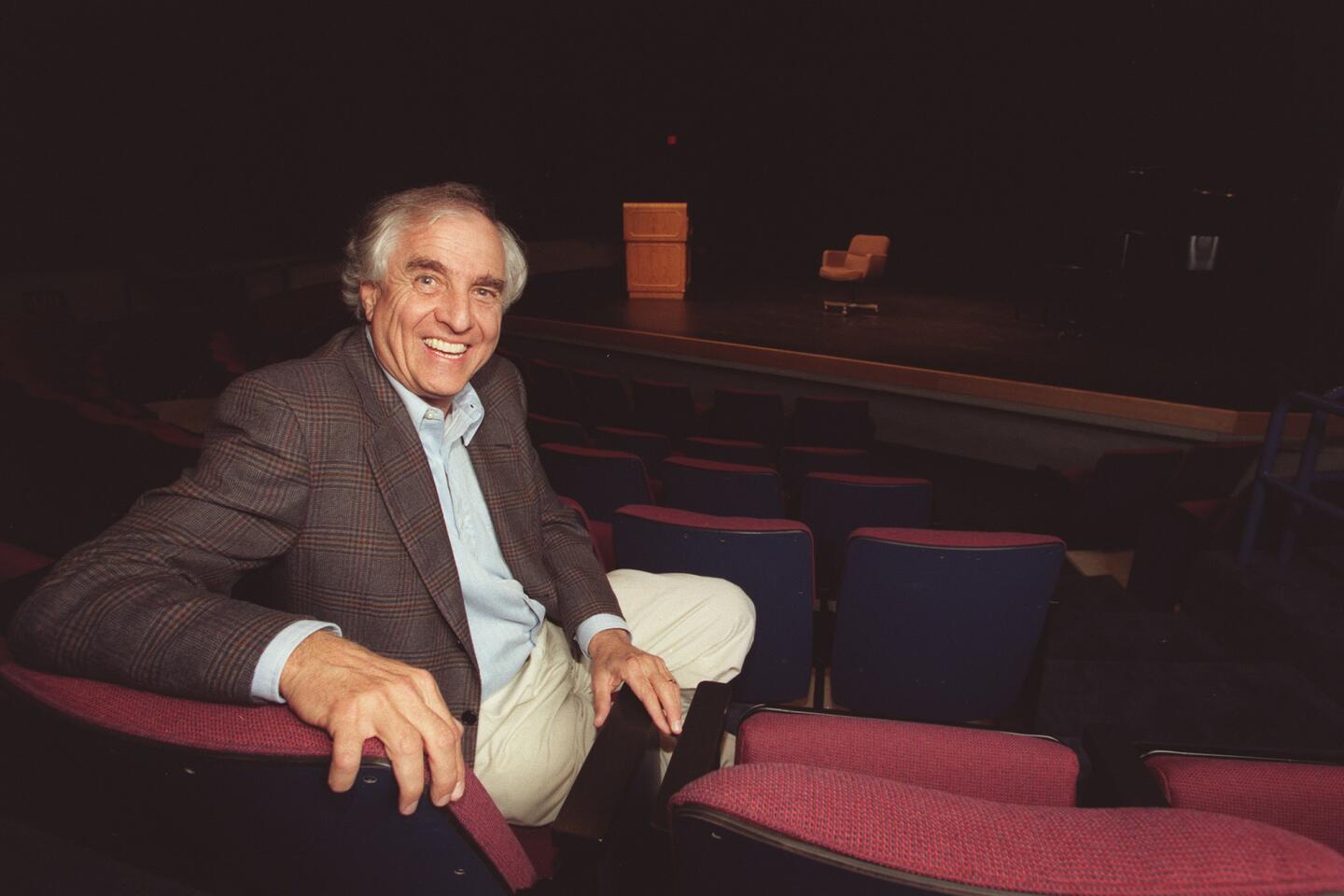

Writer-director Garry Marshall, whose TV hits included “Happy Days” and ‘’Laverne & Shirley” along with such box-office successes as “Pretty Woman” and “Runaway Bride,” died Tuesday. He was 81. Here is a 1997 Times article when he was planning the launch of his Burbank theater.

Seats. Air conditioning. Parking. Bathrooms. Cake. No alimony.

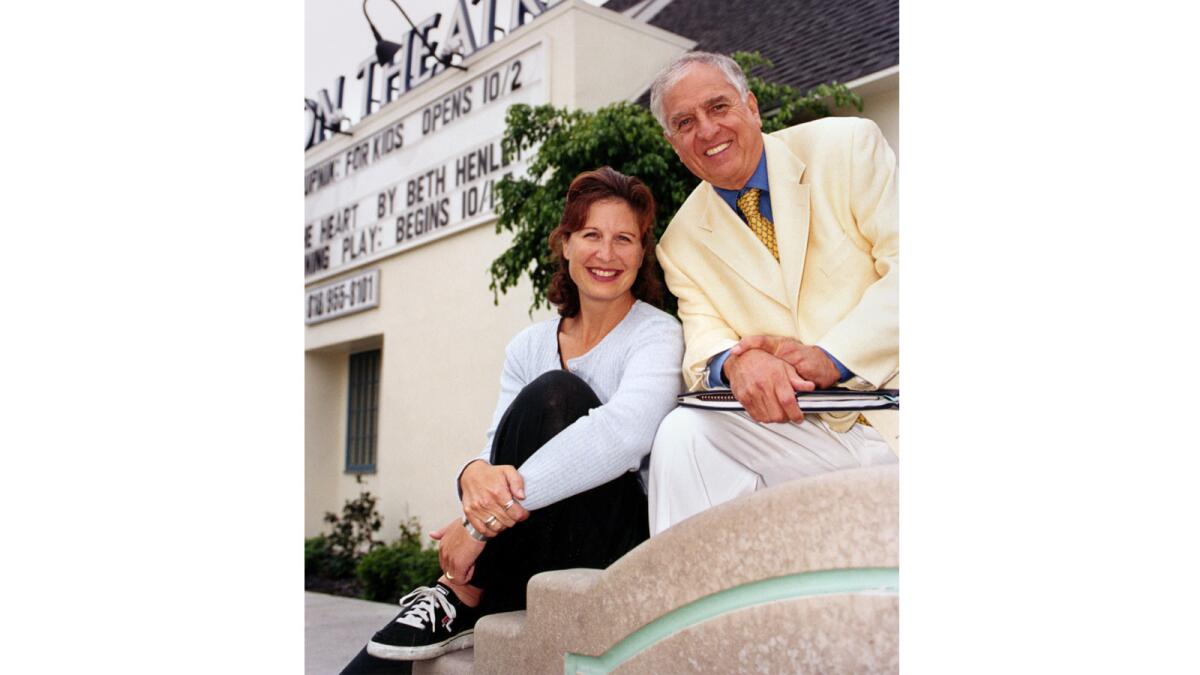

All of these were considerations in the building of the new Falcon Theatre in Burbank, Garry Marshall said.

Better known as a TV producer (“Happy Days,” “Laverne & Shirley”) and movie director (“Pretty Woman”), Marshall has gone into business as a theater proprietor. His 120-seat Falcon will open its doors Thursday, which also happens to be Marshall’s 63rd birthday. First up is the Mark Taper Forum’s annual New Work Festival of staged workshops and readings.

As he showed off his theater a few days ago, Marshall wasn’t ready to say much about the programming that will follow the Taper festival. However, he offered a wealth of insight into the big six subjects mentioned above. Future L.A. theater owners, take heed.

Seats: Comfort is essential, Marshall said. He got many of his seats in an unexpected way. During a softball game for his team the Pacemakers (in an Over the Hill League), while he was stopped momentarily at second base, the second baseman told him about a supply of seats that used to be in a synagogue, which gave them “a special karma,” Marshall said. Now they’re in the Falcon.

Air conditioning: Marshall recently saw “The Arabian Nights” on a hot day inside the Actors’ Gang Theater. “It was wonderful, but there is something to be said for seeing a wonderful play without drops of sweat coming down your face throughout,” he said. At his theater, no sweat--at least not in the audience.

Parking: “It’s all about the marriage of art and parking,” Marshall said. Since 1984, he had considered building a theater at this site, on Riverside Drive about 10 blocks from his Toluca Lake home, but it wasn’t possible until an adjacent lot became available that would permit him to include a flat parking lot on the property. The importance of this became clearer as the theater’s residential neighbors complained about the possibility of parked cars clogging their streets. How did they express this? “They came and yelled at us.” Including a few spaces at nearby sites, the theater can now accommodate 95 cars with free parking. Mused Marshall: “95 spaces? Yeah, we’ve got a shot at making that work, even in L.A.”

Bathrooms: “We have four stalls in the women’s bathroom,” bragged Marshall. (Many of the smaller L.A. theaters offer only one toilet, in a unisex restroom.) Marshall, a former journalism major at Northwestern University, advised his interviewer to begin the article by reporting this startling bathroom breakthrough. The backstage facilities aren’t shabby, either, he said. When George C. Scott starred in “Wrong Turn at Lungfish,” which Marshall co-wrote (with Lowell Ganz) and directed at the Coronet Theatre in 1992, “he wanted his own bathroom. If he shows up again, we’re ready.”

Cake: While in the Army in postwar Korea, Marshall and a buddy were cleaning their guns one day, Marshall said, when the other guy, Marc P. Smith, announced that he’d like to run a theater when he got back home. He went on to do just that--Smith has now operated the Worcester Foothills Theatre in Massachusetts for 24 years. Marshall consulted him for tips, “and one of the first things he told me was how you cut cake into so many slices and sell them for $3.50 each [at the concession stand in the lobby]. That could pay for some good productions.”

No Alimony: Marshall wouldn’t say how much he’s spending on the Falcon, but he observed that--unlike some other Hollywood powers--he owns no yacht and pays no alimony, having been married to retired nurse Barbara Marshall for 35 years. “Alimony has hurt the theater,” he declared.

Marshall professes a lifelong fondness for the theater. He has been seeing shows since he was growing up in the Bronx, when his mother, a dancing instructor, took him to Broadway musicals. She told her son “that was the best way to entertain people,” Marshall said, but he was diverted into another way: television. He made occasional forays on stages, however. His play “Shelves” was mounted at an Illinois dinner theater in 1973, and he plans to do it again at the Falcon--”I decided that the banging of forks and knives wasn’t what I wanted in the background.”

In 1980, Marshall’s play “The Roast” (co-written with Jerry Belson) closed after only four performances on Broadway, and he soon decided that he’d prefer his own theater, close to home. “I was always trying to find art near my house. I didn’t want to go direct a movie in Yugoslavia during the winter. I wanted a small theater to do my own plays and lectures.” (He had become a lecturer on the college circuit after his sitcom success in the late ‘70s.)

Design plans for a theater began in 1984 but were sidetracked by “bad financial trouble” in the mid-’80s. “I pretty much lost the money I made in TV. But then, lo and behold [in 1990], came ‘Pretty Woman,’ and I wasn’t so broke after all.”

At first, Marshall’s newly endowed theatrical interests were expressed through “Wrong Turn at Lungfish,” which opened at the Steppenwolf Theatre in Chicago in 1991. He fell “totally in love with theater” there. “When things went wrong, I heard the same curse words spoken over a $400 piece of linoleum as I heard over $1 million problems in the movies. But I figured, ‘We can solve it. It’s not a million dollars.’ ” While in Chicago, he received assistance during the rewrite process from playwright Terrence McNally, with whom he had worked when he directed McNally’s screen adaptation of his play “Frankie and Johnny in the Clair de Lune.” Of McNally, Marshall said, “I taught him how to do a screenplay, and he taught me how to do a play.”

After “Lungfish” played in L.A., it moved to New York, where Frank Rich of the New York Times didn’t like it. This renewed Marshall’s interest in having an L.A. theater “where I could hide from Frank Rich.”

Rich is no longer a critic, but finally Marshall’s theater is ready for action. He named it after the Falcons, a group he hung out with in the Bronx as a teenager. He thereby avoided calling it the Marshall Theatre, and he enjoys explaining why: His name was attached to a facility at the private school his daughter attended, after he and his wife donated the most significant contribution to the building’s capital campaign. But later, at a dinner party, Marshall overheard someone attributing the contribution to the actor E.G. Marshall. He continued eating his salad without pointing out that he was the benefactor, he recalled, but “after that, I was leery of using my own name. I didn’t want E.G. or Peter Marshall getting the credit.”

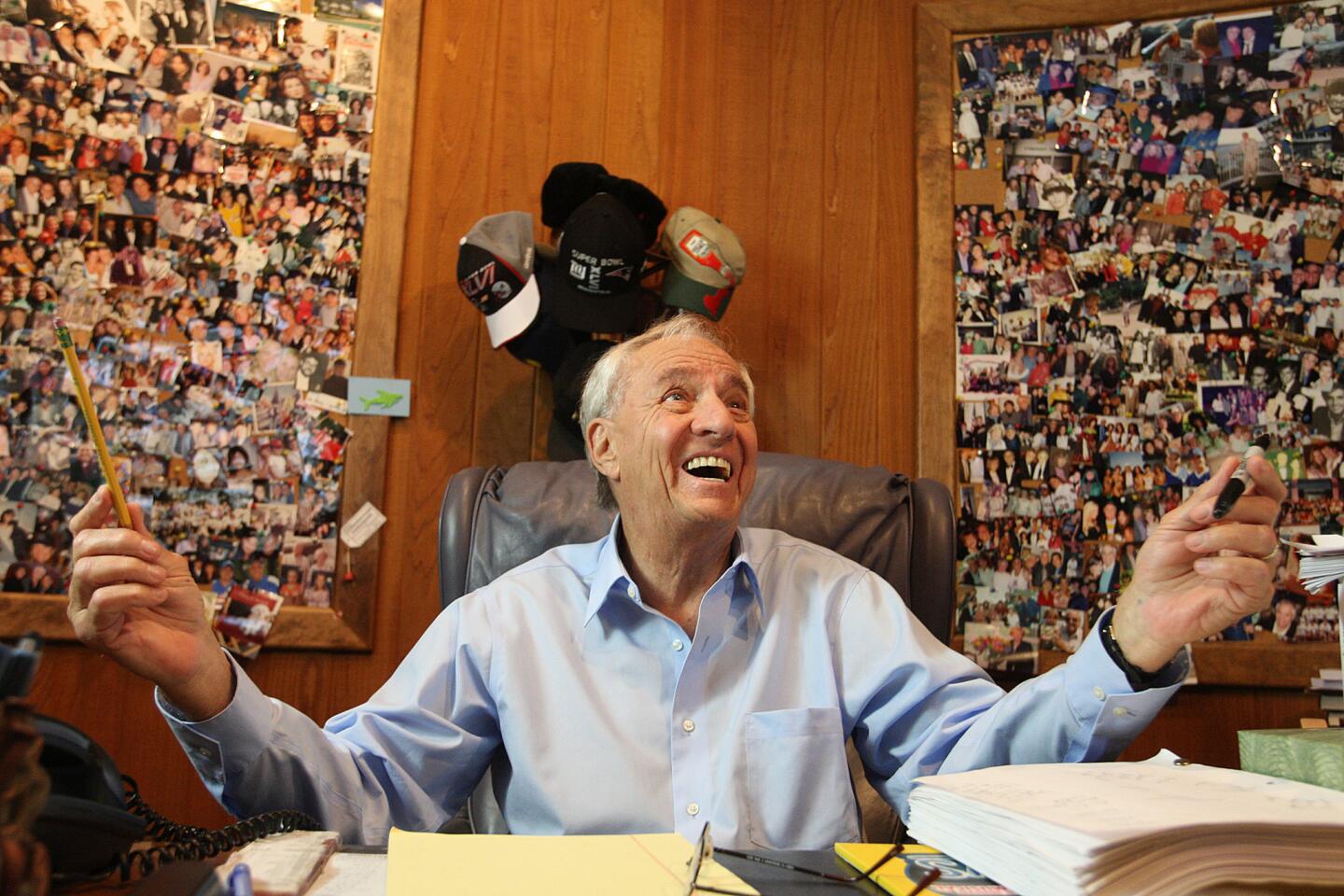

For the Falcon, Marshall hired a staff consisting of general manager Frier McCollister, director of creative affairs Kevin Larkin, and his daughter Kathleen Marshall, who supervised construction (“Don’t build a building from scratch unless a relative is on the premises all the time,” advises Marshall) and now serves as artistic associate. Marshall’s son, screen director Scott Marshall, also wanted to get involved by shooting an MTV video at the new theater, but the older Marshall said he has so far refused the request--”we’re having a fight about it.”

Marshall said his theater will emphasize new work. However, he wants to be sure playwrights know that his staff--not he--will be reading the scripts for possible production (“put that in the caption,” he requested). He did throw out a few joking references to what might play there: a festival of “Plays Nobody Understands” or a production of Samuel Beckett’s “Happy Days”--”let’s see his version of it.”

The theater seats 120 instead of the usual 99 that are permitted under Actors’ Equity’s 99-Seat Theater Plan because Marshall wants the option to present larger master classes and workshops, perhaps using some of his show-biz friends--events that wouldn’t necessarily fall into Equity’s domain. However, he promised that when the theater is used for a 99-Seat Plan show, no cheating will take place--”we’ll take the extra seats out and leave them at the Equity office if necessary--here’s my chit.”

Marshall regrets that there hasn’t been more “melding” of Hollywood and the L.A. theater scene. Studio executives believe that theater people “hate us,” he said, while L.A. theaters resent the way film and TV pluck talent away from theater gigs. He hopes the Falcon can help bridge the gap.

“Not that this little theater will change L.A.,” he said, “but at least we’ll try to mix it up.”

More to Read

Only good movies

Get the Indie Focus newsletter, Mark Olsen's weekly guide to the world of cinema.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.