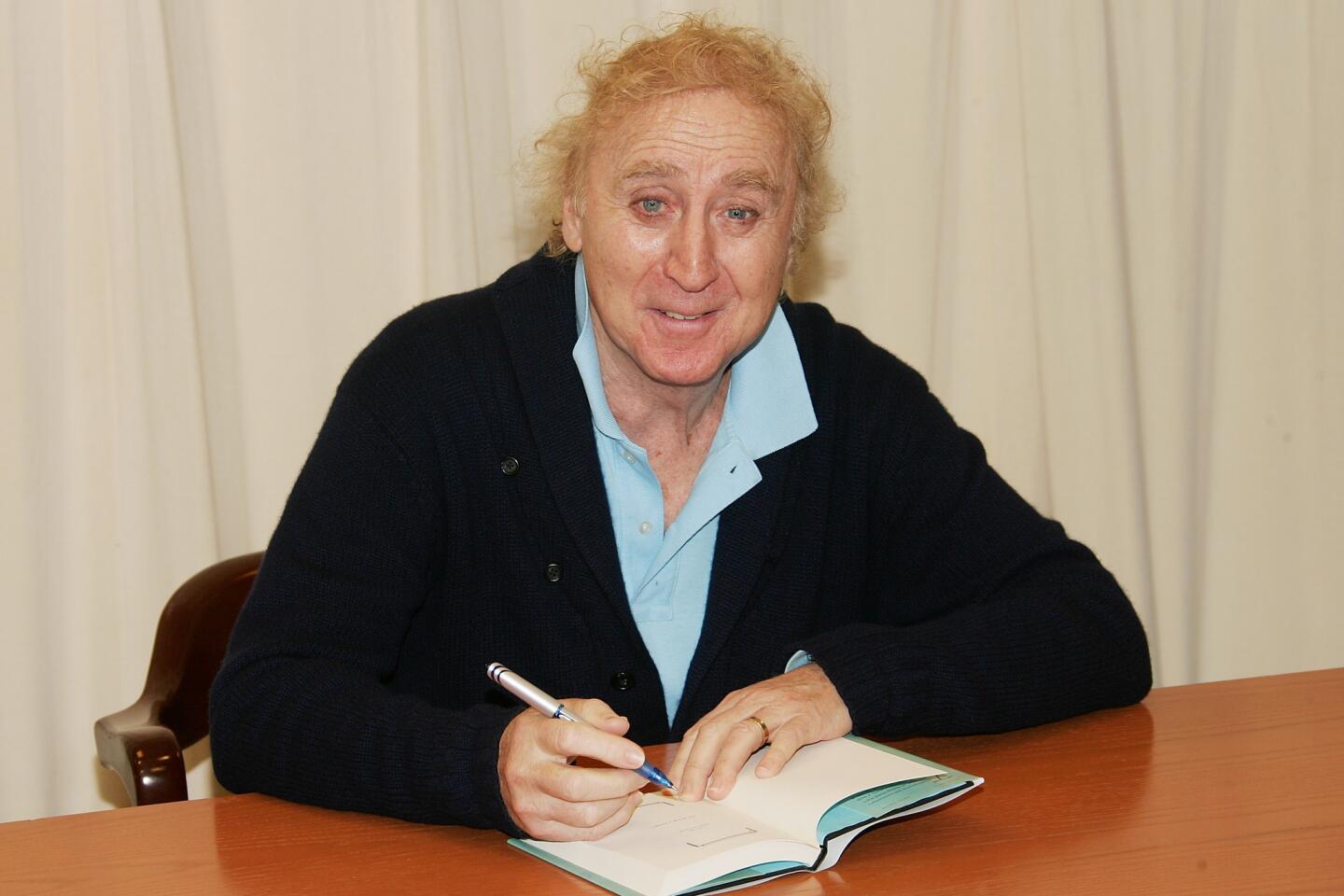

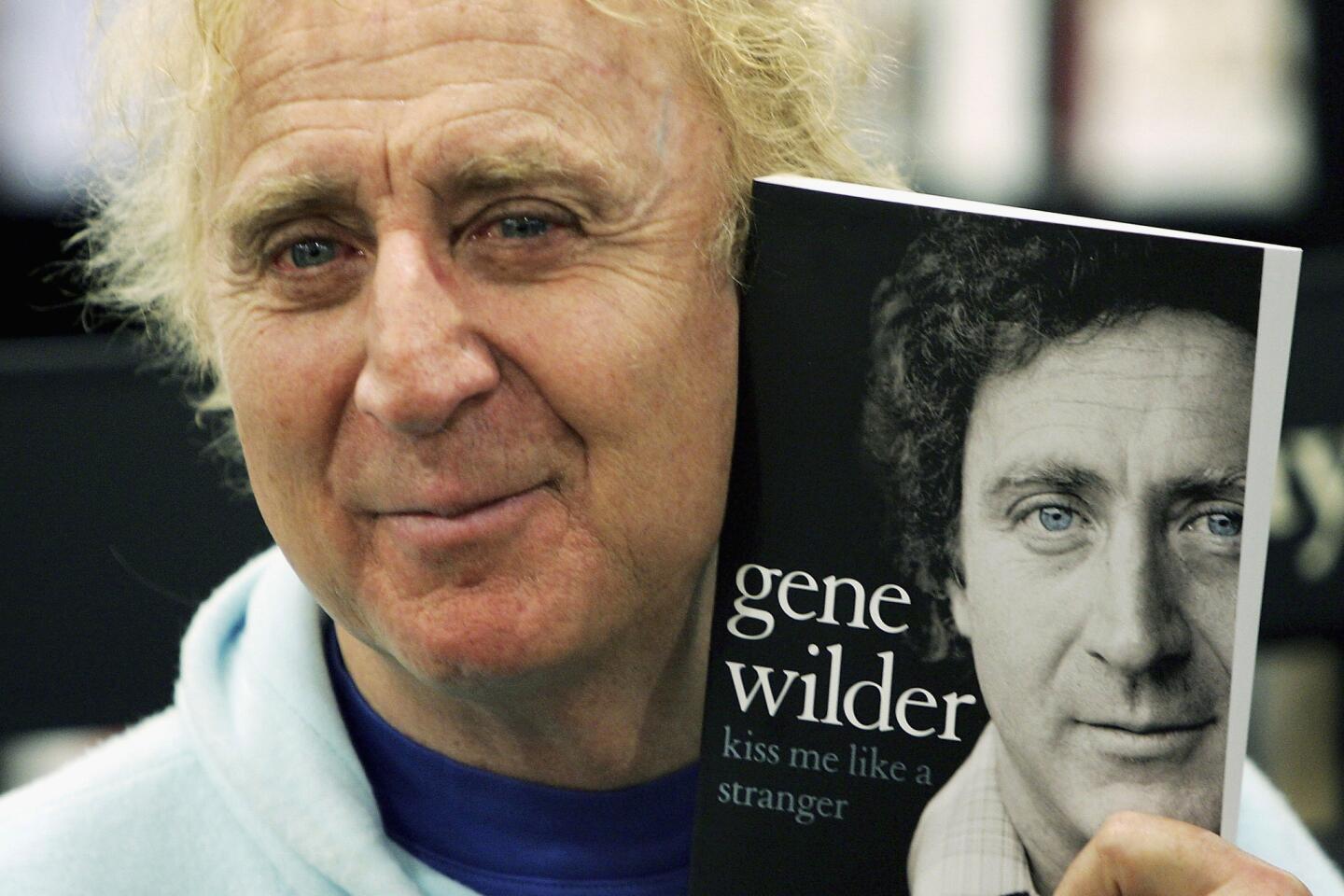

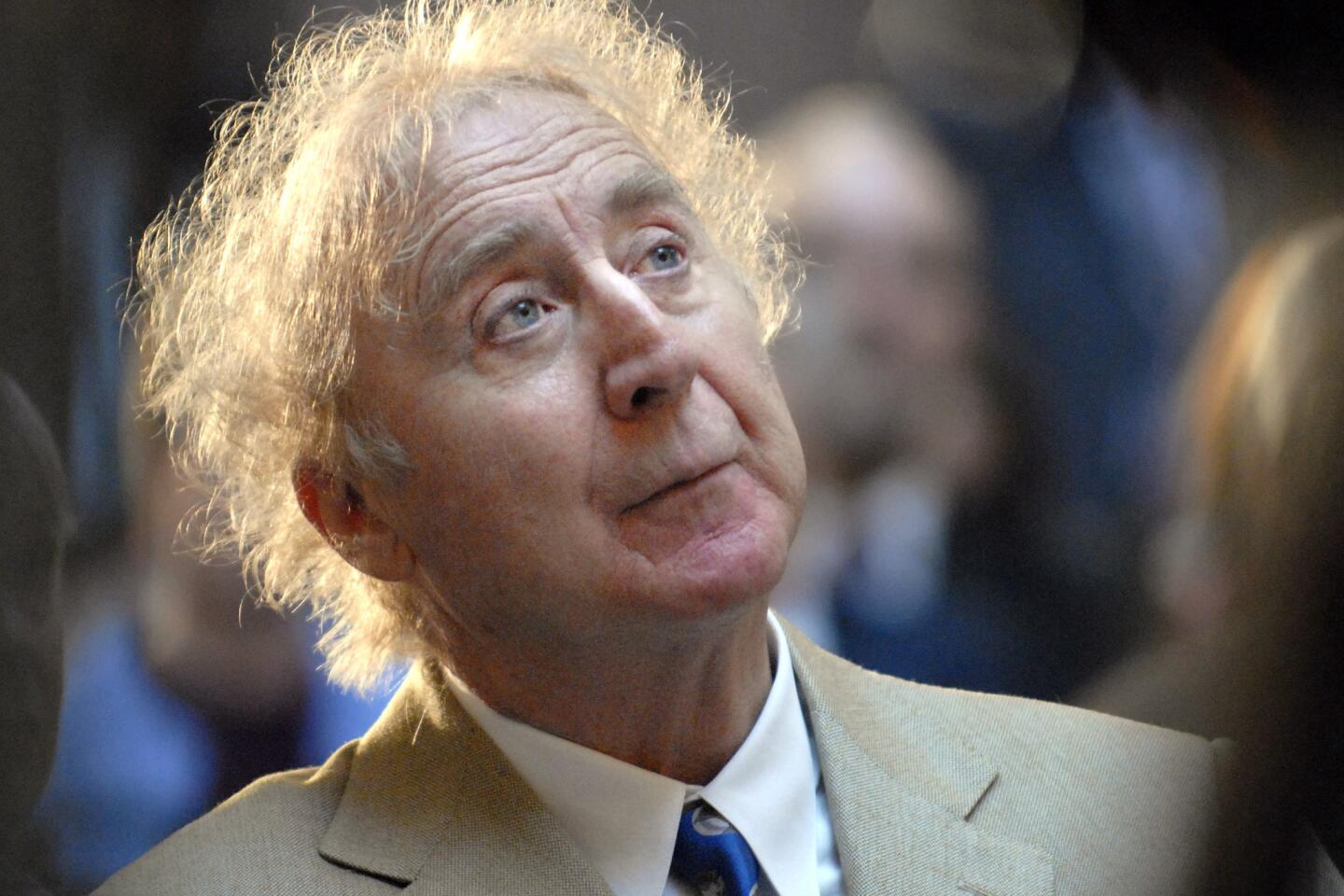

From ‘Willy Wonka’ to ‘Stir Crazy’: Remembering Gene Wilder through his five greatest performances

- Share via

When Gene Wilder was considering taking the role of the delightfully demented title character in 1971’s “Willy Wonka and the Chocolate Factory,” legend has it that his sticking point was the manner of Willy Wonka’s first appearance in the film.

Wilder demanded that the quizzical confectioner first be seen hobbling, with a cane, like some doddering recluse, as he walks to the gate to greet the five children he’d be admitting to his fantastical factory. Then his cane would stick in the red carpet, sending Wonka plummeting to the ground. But before he hit, he tucked into a roll and sprang up like an acrobat.

“I said, ‘I’d like to come out with a cane and be crippled because no one will know from that time on if I’m lying or telling the truth,’” revealed Wilder in the “Pure Imagination” documentary on the “Willy Wonka” DVD.

Wilder — who died Aug. 28 at 83 from complications from Alzheimer’s disease — wanted the audience to be off-balance, to never be sure what they were going to get from Willy Wonka.

And that was the draw of all of Wilder’s best performances. There was always mania lurking under the surface of the actor’s innocuous, somewhat frayed exterior. And what made Wilder — who approached each role with a rigor that came from training in both the Stanislavski and Strasberg methods — so irresistible was the wondrous tension of precisely when his mania would erupt.

Audiences got their first look at Wilder’s volcanic gifts in Mel Brooks’ 1967 classic, “The Producers,” in which Wilder played the (normally) mild-mannered accountant Leo Bloom who reluctantly joins the Broadway swindle hatched by the morally elusive Max Bialystock (Zero Mostel).

There are many things of note in “The Producers” (anytime “Springtime for Hitler” is invoked comes to mind), which is so resilient a film that not only has it survived a Tony-winning Broadway adaptation, it endures despite a tepid film adaptation (starring Broadway’s Matthew Broderick and Nathan Lane) of that theatrical experience.

But the moment when Wilder’s Bloom realizes the depth of their deception — that they’ve sold 25,000% of the play to a cadre of little-old-lady investors — and loses his mind is the one that resonates. “I’m hysterical. I’m having hysterics. I’m hysterical…” Mostel splashes water in his face. “I’m wet. I’m wet. I’m hysterical and I’m wet.” Mostel slaps him. “I’m in pain. And I’m wet. And I’m still hysterical.”

Watching Wilder in “The Producers” is like watching a child’s toy that has been wound up and stuck in a box, waiting to unspool.

Conversely, you spend all of 1974’s “Blazing Saddles” waiting for that eruption and it never comes. Brooks’ genius in casting his well-integrated Western — about a black sheriff sent to tame a white frontier town — was calling on Wilder to play it cool as notorious gunslinger the Waco Kid.

Wilder absolutely holds the screen as the tarnished pistolero as he tells his story to Cleavon Little’s Sheriff Bart, letting slip just the briefest glimmer of that energy: Displaying the rock-steadiness of his right hand, before bringing his left into view, twitching like a fish out of water. “Too bad this is my shooting hand,” he says.

One might think it hard to pick just one moment from “Young Frankenstein” (1974), Wilder’s final collaboration with Brooks as a director. And it is, because it is the only one of the three where Wilder is the lead — as Frederick Frankenstein, heir to his grandfather’s bring-the-dead-to-life legacy — and he’s given so much to work with. From Frederick’s insistence that it’s pronounced “Fronkenstein” to the dance number with Peter Boyle’s Monster set to “Putting on the Ritz,” “Young Frankenstein” is littered with gems.

But if comedy is all about timing, then Wilder was the master of knowing precisely how long to let a loaded moment sit, uncommented on, like a jack-in-the-box you know is going to pop.

Early in the film, Frederick is giving a lecture on the central nervous system and Wilder — as matinee-idol handsome as he ever was — calmly fields questions. That calm fades when one student presses him on his grandfather Victor’s work. “You are talking about the nonsensical ravings of a lunatic mind,” Wilder’s Frederick exclaims, getting more heated as he goes. “Dead is dead! You have more chance of reanimating this scalpel than mending a broken nervous system!”

Then, of course, he stabs himself in the thigh with the scalpel. A full 10 seconds passes before Wilder says anything else — the comedy is contained entirely within that space; waiting for the tension to break, reveling in the time it takes before it does.

Wilder made four comedies with Richard Pryor — “Silver Streak” “Stir Crazy,” “See No Evil, Hear No Evil” and “Another You” — but of them all, “Stir Crazy” has aged the best. Under the guidance of director Sidney Poitier, the class and race comedy of two showbiz wannabes who end up wrongfully convicted of bank robbery is modulated far better than in “Silver Streak” (which has a rather unfortunate blackface interlude), but still has more edge than the toothless “See No Evil” and “Another You.”

Poitier (and Pryor) ably guide Wilder through the film’s most memorable scene, in which the white comedian tries his best to “act black” in order to impress on the other inmates that they are not to be messed with. And that bit of physical comedy — arms akimbo, strut modulated with what seems to be a scientific articulation of “soul,” neck apparently unable to support a grown man’s head — has formed the nucleus of every other white comedian’s take on blackness.

It is a bravura bit of performance — slightly uncomfortable to watch today, but like so much of what Wilder did throughout his career, it is the result of a man in supreme command of his own gifts.

Wilder knew exactly how he wanted you to feel and knew exactly how to make you feel it.

It had been more than a decade since anyone had seen Wilder on screen, his last credit is as a voice on the children’s television show “Yo Gabba Gabba.” He claims to have stepped away because he felt removed from what comedy had evolved into, as reliant as it had become on the outrageous and the profane. And, after his beloved wife Gilda Radner died of cancer in 1989, perhaps his heart just wasn’t in it.

Which leaves today’s audiences to feel his loss even more acutely. The Wilder we got was of the highest comedic order, but one wishes there was more Wilder to turn, and return, to.

ALSO

Gene Wilder dies at 83; ‘Willy Wonka’ star and Mel Brooks collaborator

Gene Wilder on his first turn as a romantic lead in ‘Funny About Love’

Gene Wilder discusses his acting successes and preference for writing

Why Gene Wilder gave Gilda Radner’s name to Cedars-Sinai for its cancer research program

A comic book I wrote imagined snipers shooting at police. Now that frightening reality haunts me

The emotional hooks of ‘Hamilton’: Why the soundtrack makes me cry every single time

More to Read

Only good movies

Get the Indie Focus newsletter, Mark Olsen's weekly guide to the world of cinema.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.