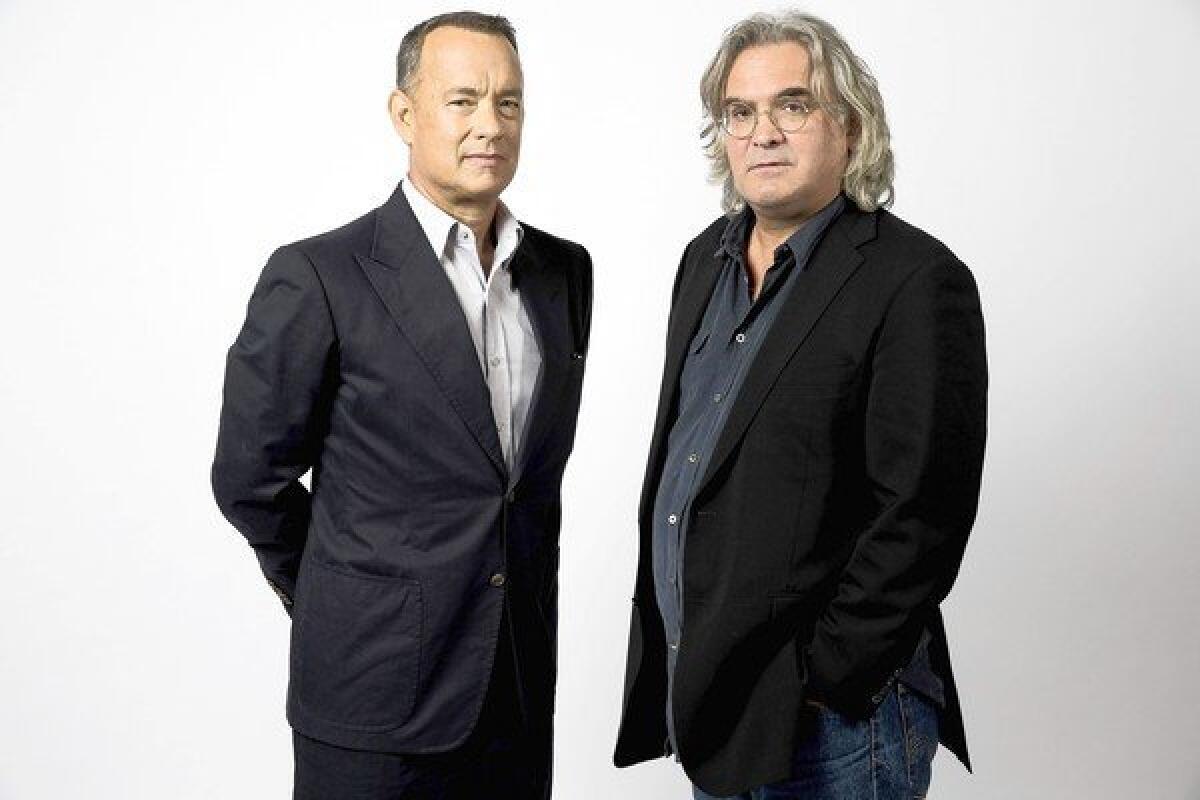

Tom Hanks, Paul Greengrass navigate challenges of ‘Captain Phillips’

- Share via

Aboard the USS Truxtun last spring, Tom Hanks and director Paul Greengrass were about to shoot what they hoped would be a powerful scene in their new movie, “Captain Phillips,” when a Navy captain intervened.

“He said, ‘You know that would never happen,’” Greengrass said.

It was a delicate moment in the production. Working in the claustrophobic spaces of a U.S. Navy destroyer sailing off the coast of Virginia, the cast and crew had prepared for a shot where two key characters converge. Instead, after conferring with the captain, they quickly changed their dramatic course, and Greengrass enlisted a Navy medic to improvise with Hanks.

PHOTOS: Tom Hanks - Career in pictures

“It was hairy,” Hanks said of shooting the emotional sequence.

The resulting depiction of shock and disorientation is one of the most memorable scenes in Hanks’ 29-year film career.

“Captain Phillips” is based on the true story of Richard Phillips, a merchant mariner who was captaining the Maersk Alabama, an American cargo ship, when Somali pirates hijacked it in 2009 and the U.S. Navy undertook a dramatic rescue. From a screenplay by Billy Ray inspired by Phillips’ memoir, Greengrass shot the logistically complex thriller on the open ocean off ports in Malta, Morocco and Virginia, with a cast of young Somali American men appearing in their first acting roles and a flotilla of sets that included a working container ship, two Navy destroyers and an aircraft carrier.

The movie, which opens Oct. 11, pits two captains, Hanks’ Phillips and a desperate Somali pirate named Muse (newcomer Barkhad Abdi), against each other in the unforgiving waters of the global economy. Captain Phillips is trying to deliver 17,000 metric tons of cargo to Mombasa, Kenya, including electronics, textiles, cars and food aid ultimately bound for Somalia; Muse is trying to deliver a fat ransom payment to a Somali warlord.

Sailing together

In the commissary on the Sony Pictures lot in Culver City last weekend, Greengrass and Hanks described what the director called the “three-legged race” of making “Captain Phillips” together with their crew of 200. Greengrass, his shaggy gray hair flopping into his wire-rim glasses, was intense and weary from travel. Hanks, smartly groomed for two public screenings happening that night, was avuncular and upbeat. (“People are usually smart and nice. Are you smart and nice?” he asked a reporter.)

They’re an unlikely pair. Hanks, 57, became Hollywood’s A-list everyman by playing a collection of affable heroes, an HIV-positive attorney in “Philadelphia” (for which he won his first Oscar), a slow-witted Alabamian in “Forrest Gump” (for which he won his second), a gruff World War II Army captain in “Saving Private Ryan.” The British-born Greengrass, 58, built his career as a documentarian before turning to propulsive real-life thrillers such as the Northern Ireland-set drama “Bloody Sunday” and the 9/11 hijacking story “United 93” and the more commercial spy movies of the Jason Bourne franchise.

“He’s the boss, I’m the guy,” Hanks said. “But boy, we better be making the same movie here, otherwise it’s gonna be really difficult.”

Hanks, attracted by a contemporary hero’s story, came aboard the project first, and met with Phillips early on to learn about his experiences.

“The burden of being a captain is the thing that was a surprise to me,” Hanks said. “It’s a pressure-filled job that never stops. How much fuel and how fast you’re burning it and when you’re supposed to be in Mombasa and who you’re going to have to bribe once you get into a port.”

(Even 41/2 years after the hijacking, that responsibility is still weighing on Phillips; nine members of his 20-man crew are suing the shipping company for endangering them, saying Phillips ignored warnings about pirates in the area.)

PHOTOS: Hollywood backlot moments

Greengrass joined the production later, after producers Scott Rudin, Michael De Luca and Dana Brunetti persuaded him that they wanted more than an adventure tale, he said. “Lots of films could have been made about this material,” Greengrass said. “What they wanted was raw, authentic, complex. They didn’t want it simple.”

Picturing pirates

Somalia’s combination of extreme poverty and political instability has made it fertile ground for the criminal enterprise of piracy. In 2009, when the film takes place, Somali hijackings were on the rise, with 45 other vessels attacked that year. Since then, as shipping companies have employed armed security guards and international naval forces have arrested more than 1,000 pirates, the practice has diminished.

Greengrass wanted to portray the pirates as victims of economic pressures. An early scene where too many men vie for too few spots on a pirate skiff is deliberately reminiscent of the longshoremen crowding the docks in “On the Waterfront.”

When Hanks and Greengrass embarked on the project, they discussed the point of the movie over a series of phone calls and meetings.

“We decided it was about, ‘Are we going to be OK?’” Greengrass said. “And we wrote it down on a little piece of paper, which I’ve still got.”

PHOTOS: Billion-dollar movie club

Anyone who followed the news reports of Captain Phillips’ story knows the answer to that question — the captain lives and has even attended some early promotional screenings of the film.

But for Hanks, who will appear this year in the rather different role of Walt Disney in the movie “Saving Mr. Banks,” the drama was in the man himself. “Everybody knows how ‘Rigoletto’ ends, but they still go to see the interpretation of the character,” he said.

“You have to make a film without knowledge of where it ended up,” Greengrass said. “If you can create your story in an unfolding present tense … that’s where character exists.”

The film begins with Captain Phillips’ wife, Andrea (Catherine Keener), dropping him off at the airport and worrying about their children but moves quickly to the decks of the cargo ship, with a cast including Michael Chernus (“The Bourne Legacy”) as Phillips’ second in command and David Warshofsky (“There Will be Blood”) as his engineer. Max Martini (“Pacific Rim”) is the Navy SEAL commander on the scene, and the men under him are played by former SEALs.

To create a feeling of immediacy on set, Greengrass took the unusual step of casting four Somali Americans who had never acted before to play the pirates — Abdi, Barkhad Abdirahamn, Faysal Ahmed and Mahat M. Ali. The roles, particularly Abdi’s, would require a sense of menace and vulnerability.

PHOTOS: Celebrities by The Times

Casting directors Francine Maisler and Debbie DeLisi found their lanky young pirate crew in the Somali immigrant community of Minneapolis, where Abdi responded to an ad for an open casting call that appeared on a local TV channel.

Within months, Abdi, whose family won a green card lottery to come to the U.S. when he was 14, was training to film on the unstable pirate skiffs. “We learned swimming, fights, stunts, climbing,” said Abdi, 28. “I have a thing for danger.”

Greengrass deliberately kept Abdi and the pirate actors from meeting Hanks and the men portraying the Alabama’s crew to capture a moment of excitement on camera and to prevent Hanks’ stardom from intimidating the new actors.

It worked. When they shot the scene of the pirates storming the bridge of the Alabama, Hanks said, “For the first take it was incredibly harrowing. And the second take it was incredibly harrowing. And the third take we remembered how harrowing it was. And then by the fourth take, we were saying, ‘Hey, nice to meet you.’”

Greengrass’ unrehearsed, hand-held method of filmmaking, learned through his documentary background, is particularly conducive to newcomers, Hanks said.

THE ENVELOPE: Full film festival coverage

“There were no marks to hit,” Hanks said. “There wasn’t any technical thing that they had to learn how to do. Usually it’s, ‘Hey, can you not overlap? You yelled at him over his line.’ There was never any of that stuff. So they were in the environment and they were ready to go.”

Getting sea legs

Shooting on real ships added to the production’s authenticity and its inconveniences. The crew carried the cameras and lights up six flights on the cargo ship, “and there are a lot of places to bonk your head and stub your toe,” Hanks said. Others filming from small Zodiac boats alongside the large ships got seasick.

“I always thought the fun of it would be to shoot on real ships,” said Greengrass, whose father was a seaman. “It made you shoot in a way that had a sort of atmosphere about it, because you couldn’t float walls out and put the camera where you want.”

Producer Greg Goodman negotiated for the container ship used in the film and worked with the Navy, which was eager to cooperate on a movie that showed one of the service’s finer recent moments.

“There was this one tiny red button … that when Richard Phillips pushed it, signals went out all over the world,” Hanks said. “Navy SEALs started packing their gear not knowing what was going to happen. Thousands of people became involved, and that’s even before the ships showed up.”

The film, which relies on urgent camera work by Greengrass’ longtime cinematographer, Barry Ackroyd, and rhythmic cutting by his editor Christopher Rouse, got a warm reception from critics upon its premiere at the New York Film Festival last week.

Many singled out Hanks’ moment with the Navy medic: The Hollywood Reporter called it “an extraordinary scene, one for which there is little precedent,” and Variety said it was “an eruption of emotional fireworks of exactly the sort Oscar dreams are made of.”

“We’re in an era cinematically dominated by superheroes,” Greengrass said. “He’s made this wonderful career based on playing ordinary men.... You don’t have special powers, or extraordinary physical strength or mental agility.... You’ve got to operate within what’s believable or authentic … but if you do that, as Tom does, what you find is this rich reservoir of humanity.”

More to Read

Only good movies

Get the Indie Focus newsletter, Mark Olsen's weekly guide to the world of cinema.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.