The Katniss factor: What the ‘Hunger Games’ movies say about feminism, and war

- Share via

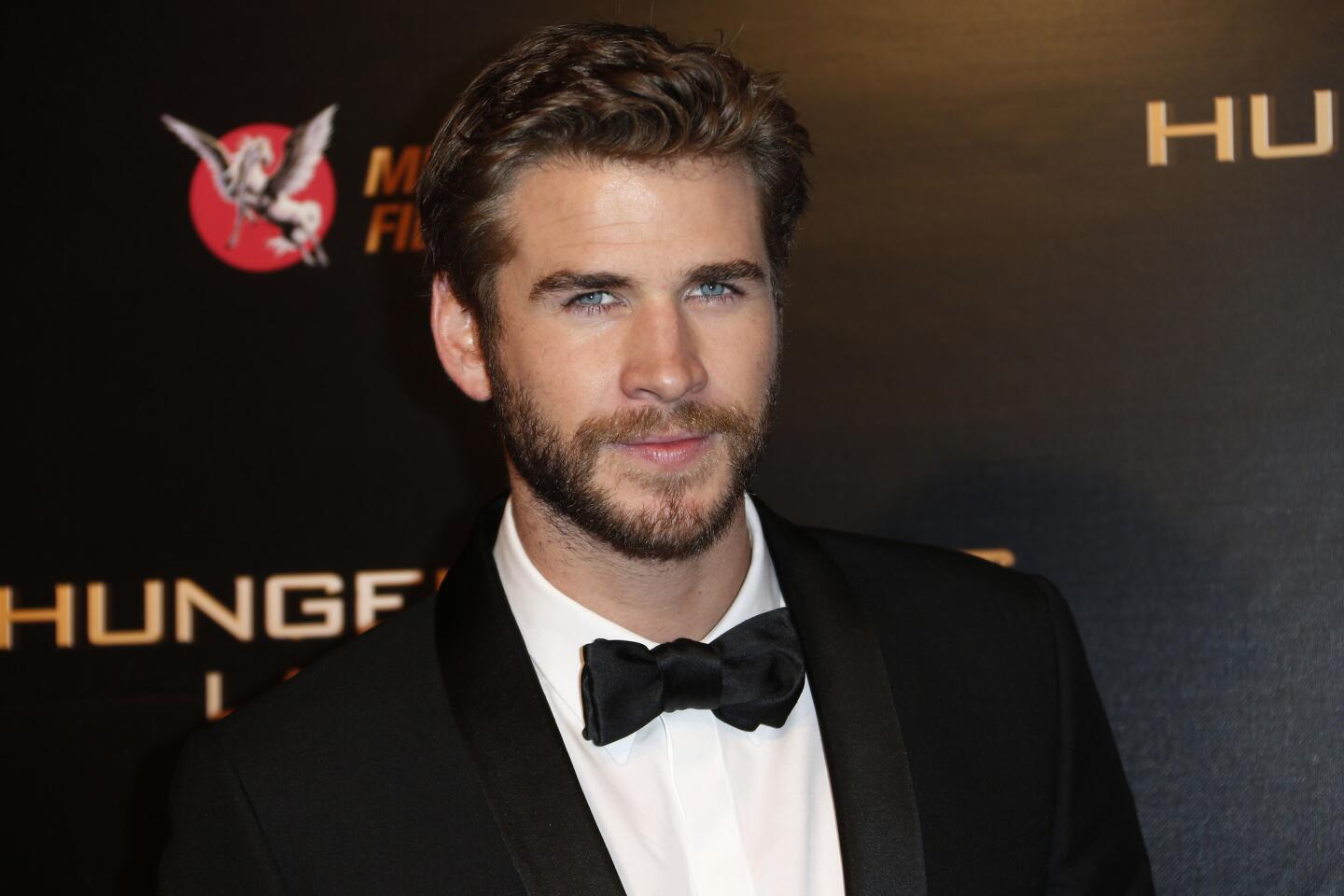

Throughout the new “Hunger Games” movie, the fourth and final in the dystopian series, heroine Katniss Everdeen’s name is intoned with grave sincerity. The manipulative President Snow whispers it, as one does of a worthy rival; her battle partner and occasional romantic interest Gale Hawthorne utters it to suggest a noble comrade.

But the most telling invocation comes early in the film. “It’s Katniss,” belts out Peeta Mellark, her other battle partner and romantic interest, compromised and angry as he lies in a hospital bed. “It’s [all] because of Katniss.”

SIGN UP for the free Indie Focus movies newsletter >>

Much has indeed happened thanks to Katniss, a name you couldn’t dream up if you tried and now can’t imagine not existing. The character has become a kind of cultural shorthand — an archetype, someone who has deepened our understanding of armed conflicts and paved the way for a political movement. And that’s just off the screen.

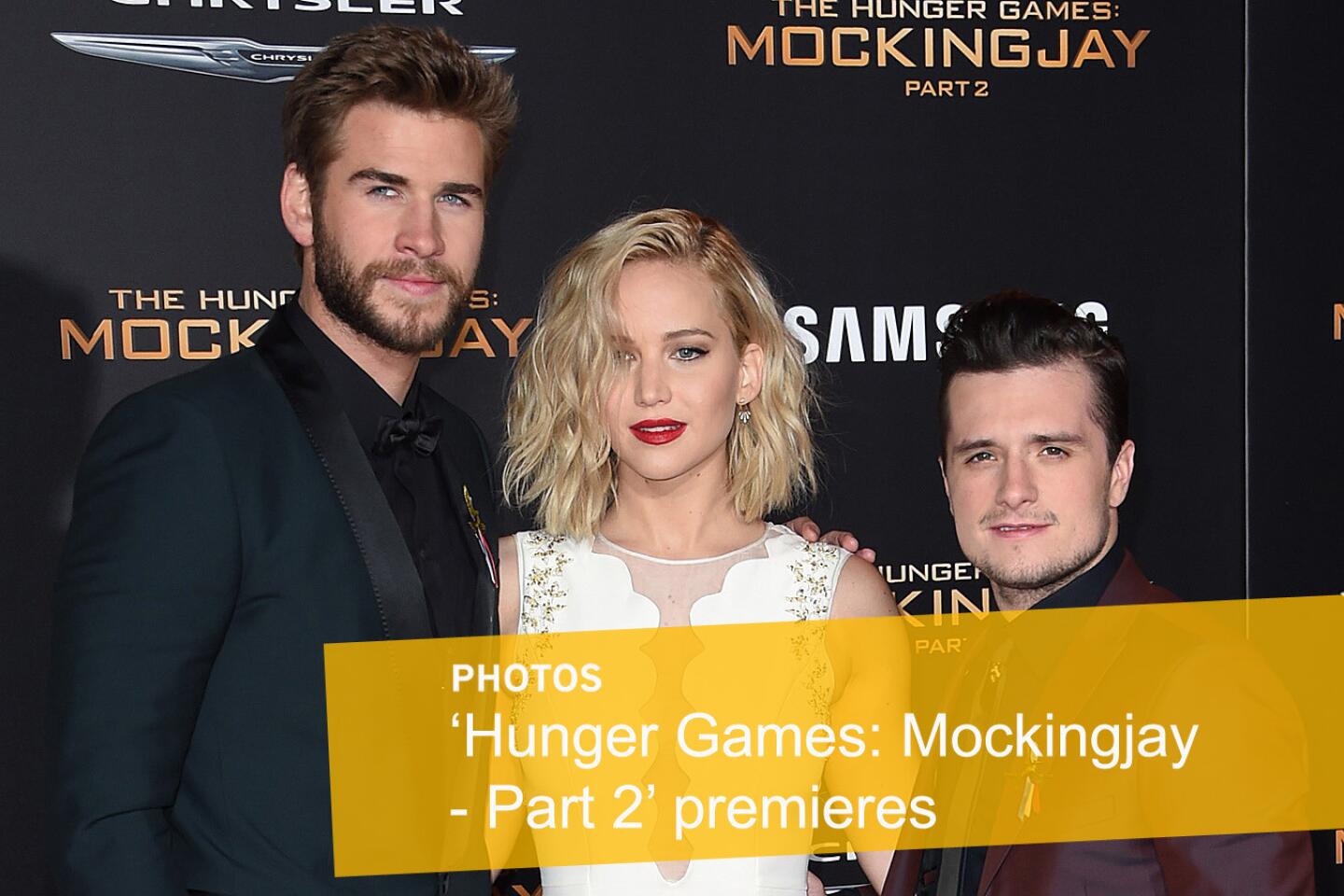

As the Lionsgate franchise winds down with this week’s release of “The Hunger Games: Mockingjay — Part 2,” the film and its lead character reside in a far different world than the one in which they began. And many of those differences came because of “The Hunger Games” films.

There is, of course, the money. The franchise that started with novelist Suzanne Collins and was largely directed by Francis Lawrence has taken in $2.3 billion globally, with more on the way. Every year since 2012, at least 35 million tickets have been bought in the United States to a new “Hunger Games” movie. More Americans on average have come out to see Katniss in a given film than they have Harry Potter.

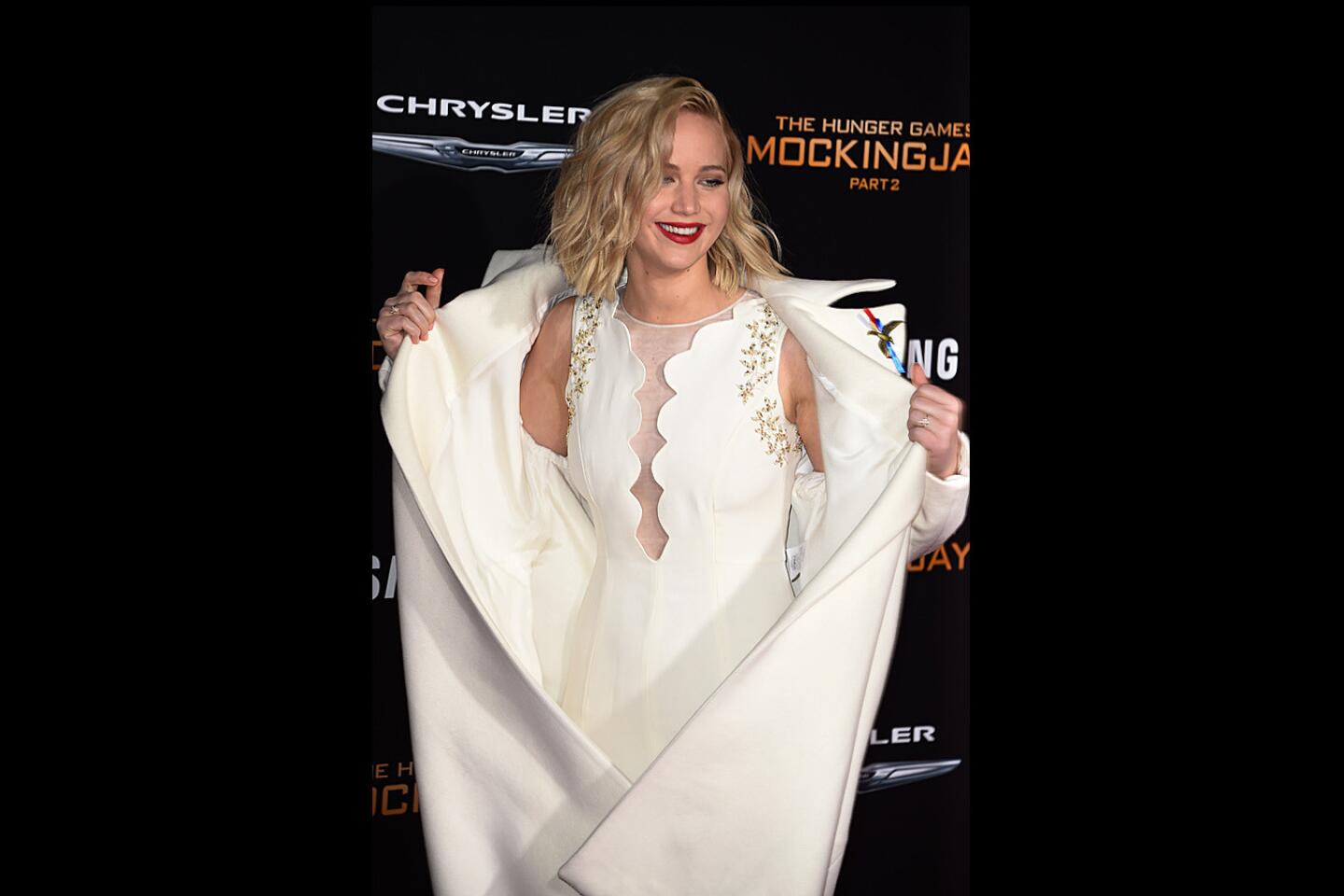

But the effects go beyond sheer popularity. As played by Jennifer Lawrence, Katniss, with her bow and arrow, has inspired a generation to lift up their weapons, both literally (the surge in archery lessons) and otherwise. She is often unsmiling, efficient and “male-like,” by the chestnutty Hollywood definition, in which female characters are rarely foremost and even less frequently autonomous.

Before “Hunger Games,” Hollywood somehow couldn’t conceive of a fully formed, villain-thwacking heroine in a top-tier franchise. Sure, some swings had been taken. But they were exceptions — pre-made stars in one-offs (Angelina Jolie in “Salt” or “Wanted”) or one-dimensional types in B-movie serials (Milla Jovovich’s “Resident Evil” or Kate Beckinsale’s “Underworld”).

Katniss, on the other hand, was, almost from the start, confident but complicated, bold but human. “She’s just so relatable and she’s not a superhero — she feels real, she feels lost, she feels reluctant,” said director Francis Lawrence. “She doesn’t want to be a leader, she doesn’t want to be part of a rebellion.”

If the character was sometimes caught in a love triangle, a Bridget Jones touch that doesn’t exactly scream postfeminist consciousness, she spent much of the rest of the time knocking away at glass ceilings, the Hollywood lady hero whose power comes from thoughts and actions more than sexuality.

The franchise, to be sure, did not always ace the Bechdel test — the metric in which movies are gauged by whether they feature two women holding a conversation about a subject other than a man — but only because Katniss was not having very many conversations at all. She was concentrating on getting the job done.

And weighed against “Twilight,” its young-adult antecedent and box office analogue, with that series’ objectifying ways and forever-after fairy tales, “The Hunger Games” is even more progressive. Compared with Bella Swan, Katniss is Bella Abzug.

Still, the feminist-minded media studies expert Alisa Perren, who teaches at the University of Texas at Austin, cautions against extrapolating too much exuberance.

“The cultural take-up of ‘The Hunger Games’ is that a feisty, empowered female character is going to be embraced by millions of women,” she said. “I just wish more studios would listen to that message and put them on the screen.”

It’s true there have been few comparable heroines in the wake of Katniss. But few is still more than zero: Tris Prior of the “Divergent” series is clearly walking in Katniss’ footsteps, as is the title character in “Jessica Jones,” the dark Marvel superhero series starring Krysten Ritter that was released Friday on Netflix.

And it is early. “The Hunger Games” is a single point on a rare but important continuum, a furthering of what began in the late 1990s with the TV series “Buffy the Vampire Slayer” and that will extend to unknown characters in the future.

At any rate, Hollywood studios are often the last to get the message. The culture has already grasped what’s possible, seen in Katniss a role model and a permission slip to make changes. It’s no accident that the primary spokeswoman for the resurgent issue of equal pay is Jennifer Lawrence, who created headlines recently when she underlined the challenge.

“I’m over trying to find the ‘adorable’ way to state my opinion and still be likable!” she wrote in a much buzzed-about essay for Lena Dunham’s website Lenny. “Jeremy Renner, Christian Bale and Bradley Cooper all fought and succeeded in negotiating powerful deals for themselves. If anything, I’m sure they were commended for being fierce and tactical, while I was busy worrying about coming across as a brat.”

Lawrence was actually noting her lower pay relative to those male costars in a different film, “American Hustle.” But it was a movement she could never have initiated without “The Hunger Games”; the franchise inoculated her to any lazy criticism that “women can’t open an action film.”

Whether her call is heeded remains to be seen. No single franchise, no matter how lucrative, can change an entrenched way of thinking, and for all the push for greater female representation around Hollywood, these are painful and slow frontier battles. But thanks to this franchise and its billions, there is no other star who can so compellingly make the case.

Beyond feminism, the movies’ politics have always been hard to divine — either too slippery to be cornered into one meaning or too subtle to give themselves over to demagoguery. Their genius has also been their flaw, so malleable as to allow nearly any reading, and it is perhaps less apt to talk about “The Hunger Games” as a cultural touchstone as it is a collective Rorschach test.

Much think-piece ink has been spilled positing what the movies are “really” about. Rooted in a world of post- 9/11 jitters, the franchise has been given many political coats of paint and is often viewed as a cautionary tale about the dangers of a Patriot Act police state. It has also alternately been hailed as a coded cry for the tea party movement, a call for an overthrow of capitalism, a parable for revolutions around the world and, even, a comment about competing forms of healthcare.

But that doesn’t mean the text is without substance, and it’s perhaps worth indulging one more, slightly up-to-the-moment geopolitical reading.

It is, after all, a coincidence that the latest film is coming out a week after the Paris attacks and bloodshed driven by Islamic State and an ideology that arose after Middle East government overthrows. Yet it is maybe not an accident that the franchise has come to prominence in this era, when once well-intended revolts have turned more complicated. “The Hunger Games” smartly anticipated (if did not outright take its cues from) those events. The series’ first movie was just headed into production during the wind-down to the Iraq war and the dawn of the Arab Spring, and the final one is hitting theaters as some of the more nefarious consequences of each are bursting forth.

Questions of rightness in a many-sided conflict, much like those currently hovering over Syria, are on the mind of this movie and its civil wars; so is the matter of carnage obscuring a rebellion that was once noble. As in real post-Arab Spring and Islamic State-era life, freedom from despots has not come without a toll. And as Katniss learns in this film (spoilers must be avoided, but fans will understand), the opposite of a dictator is not always democracy.

A hit franchise shouldn’t be saddled with too much cultural import, but it doesn’t exist apart from that culture either. Millions will turn out to see the final “Mockingjay” movie in the next few weeks, then will turn their attention elsewhere. Whether it’s about feminism or pop culture, storytelling or politics, “Hunger Games” will continue offering its pointed lessons well after studio accountants have stopped keeping track, long after Katniss has zeroed in on a target and shot her last purposeful arrow.

Twitter: @ZeitchikLAT

Los Angeles Times staff writer Meredith Woerner contributed to this report.

ALSO:

Omnipresent Jennifer Lawrence dances with Fallon, talks Chris Pratt sex scene, pranks Smosh

More to Read

Only good movies

Get the Indie Focus newsletter, Mark Olsen's weekly guide to the world of cinema.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.