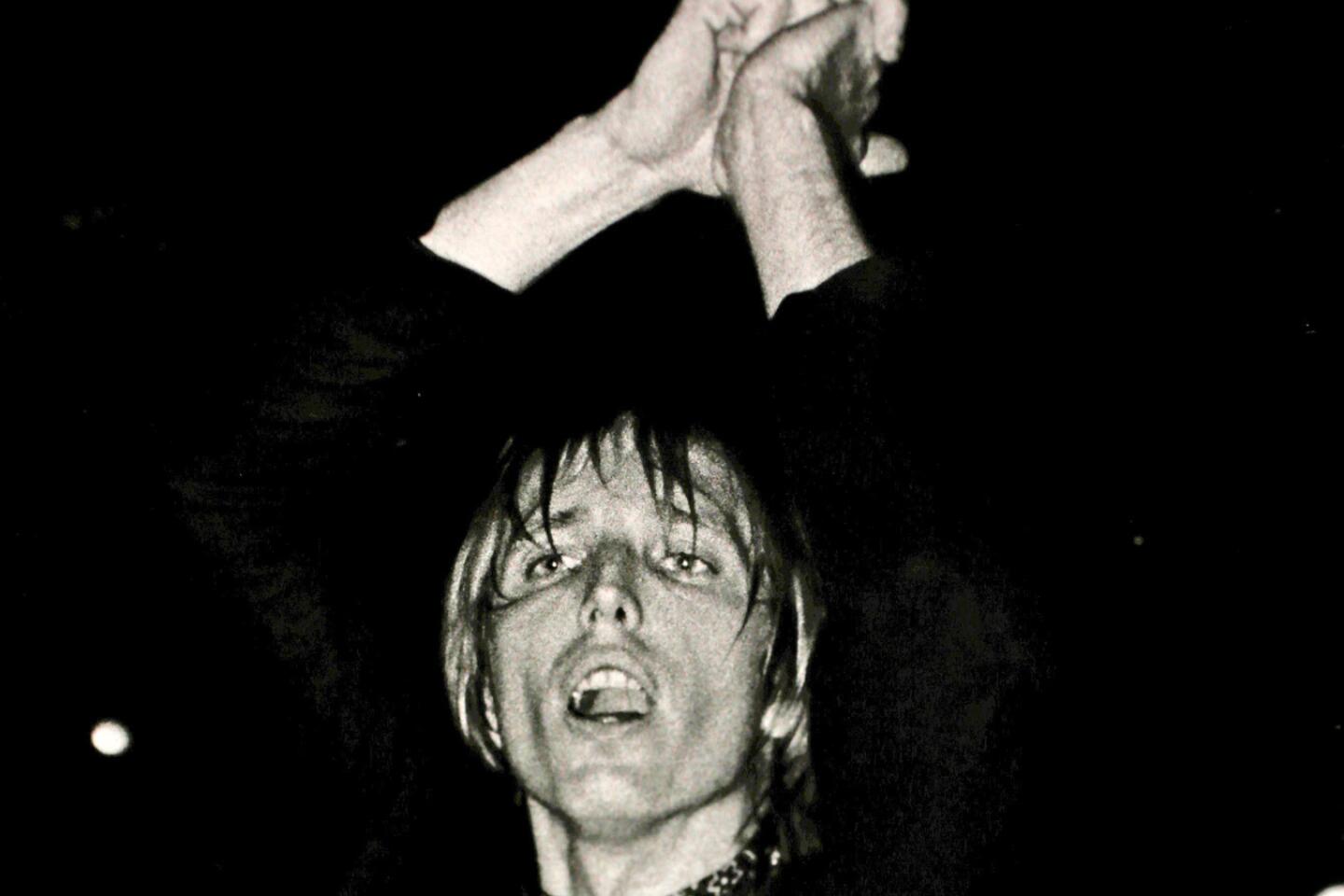

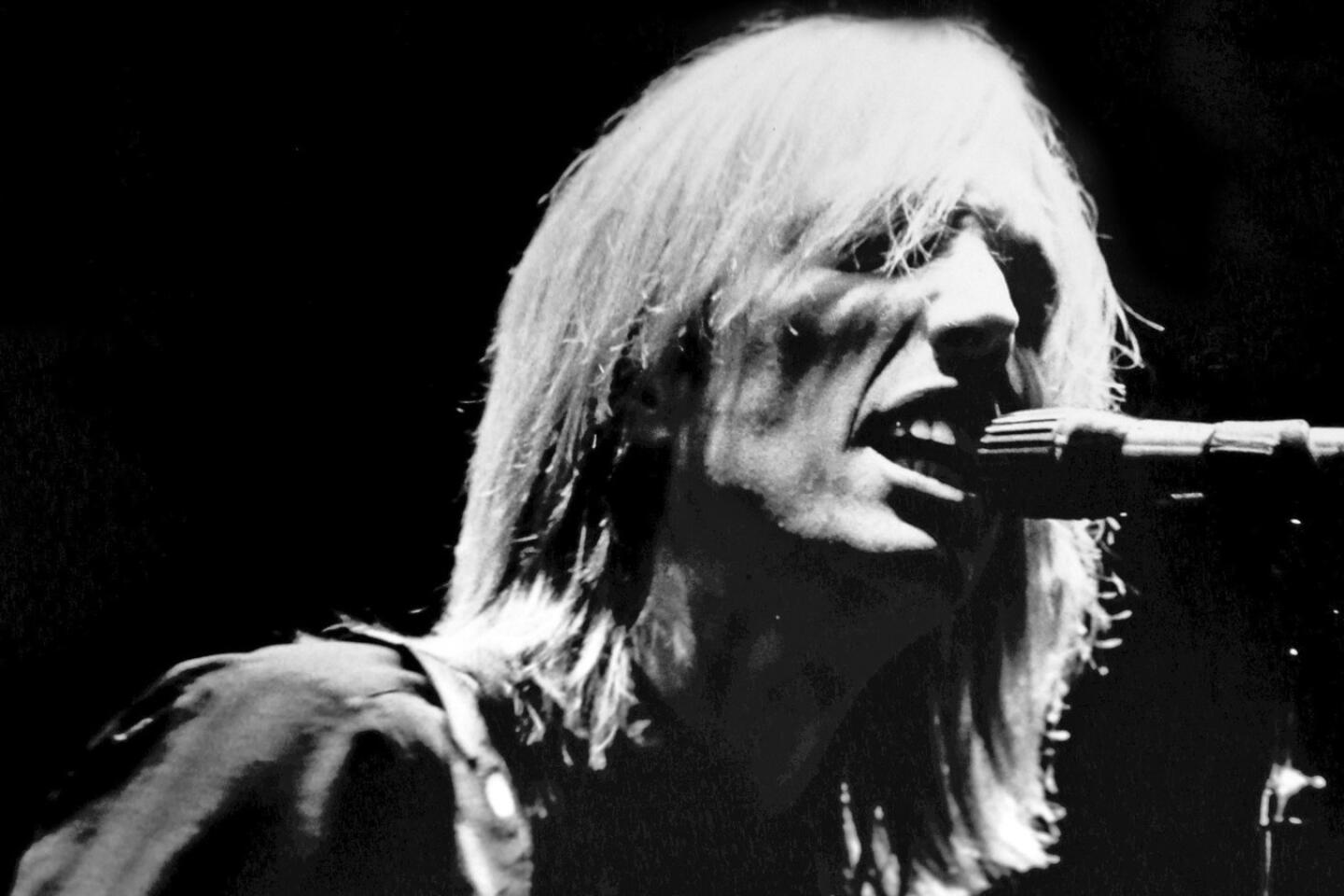

From the Archives: For Tom Petty, a songwriter’s greatest achievement is to ‘get someone to think about things’

- Share via

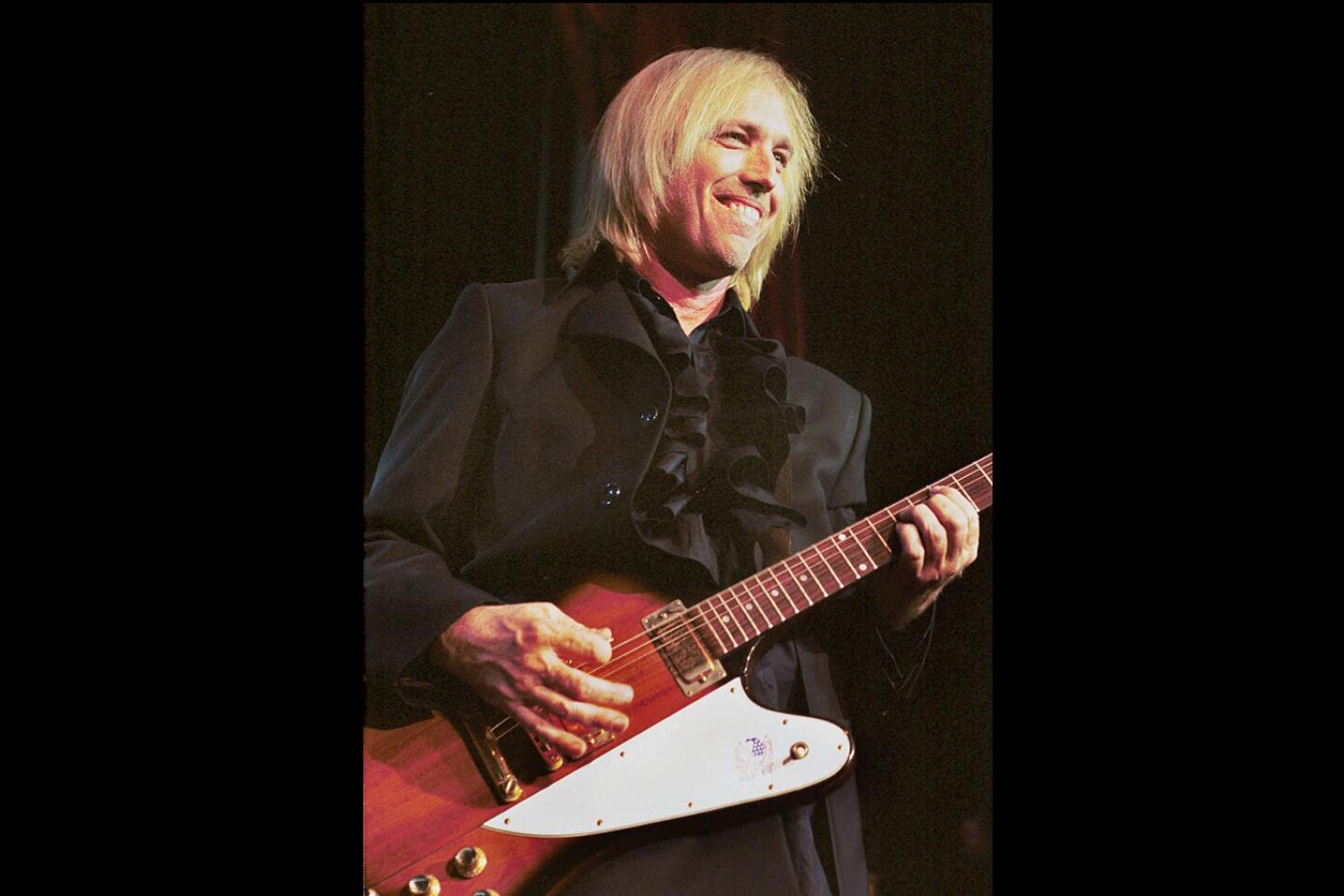

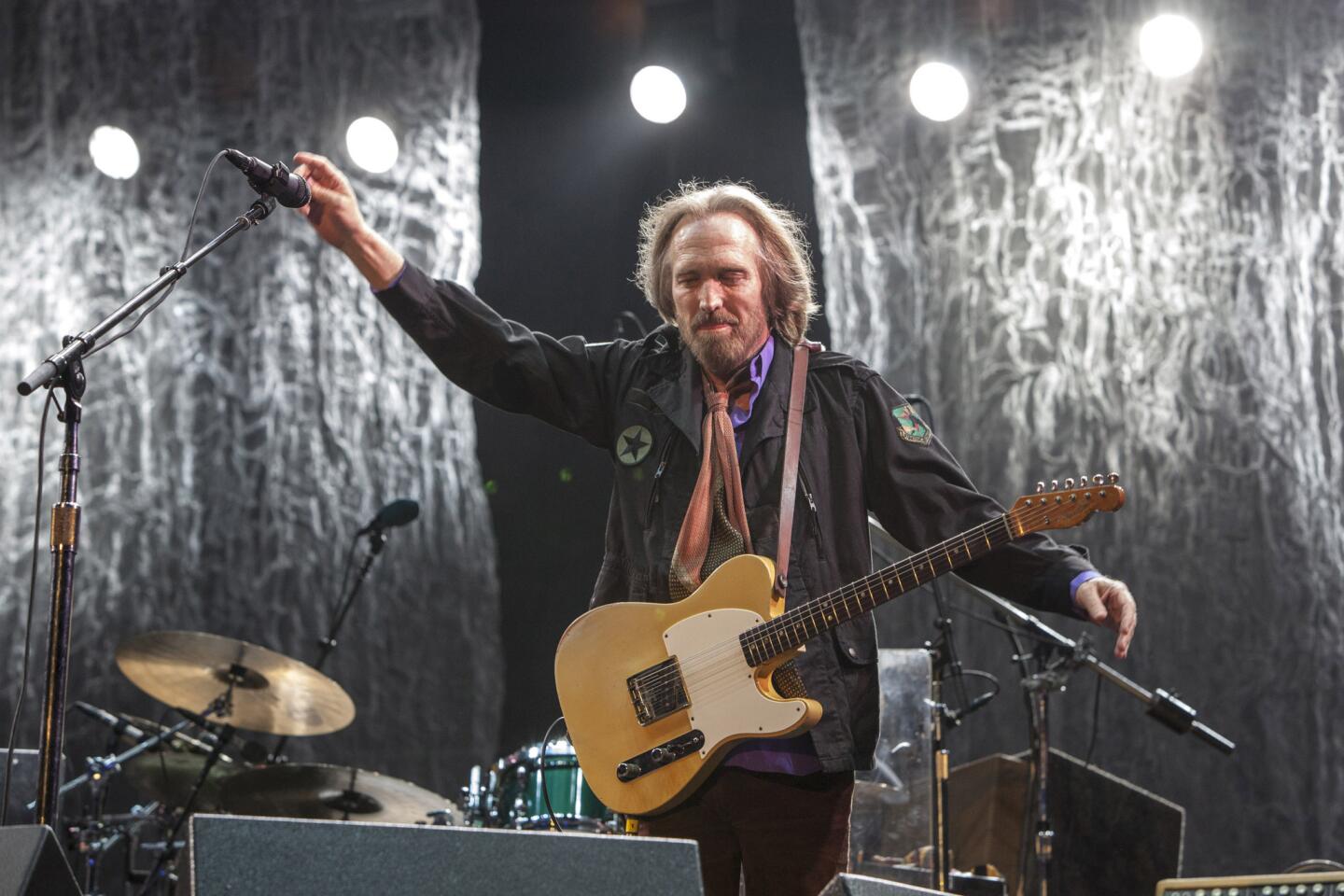

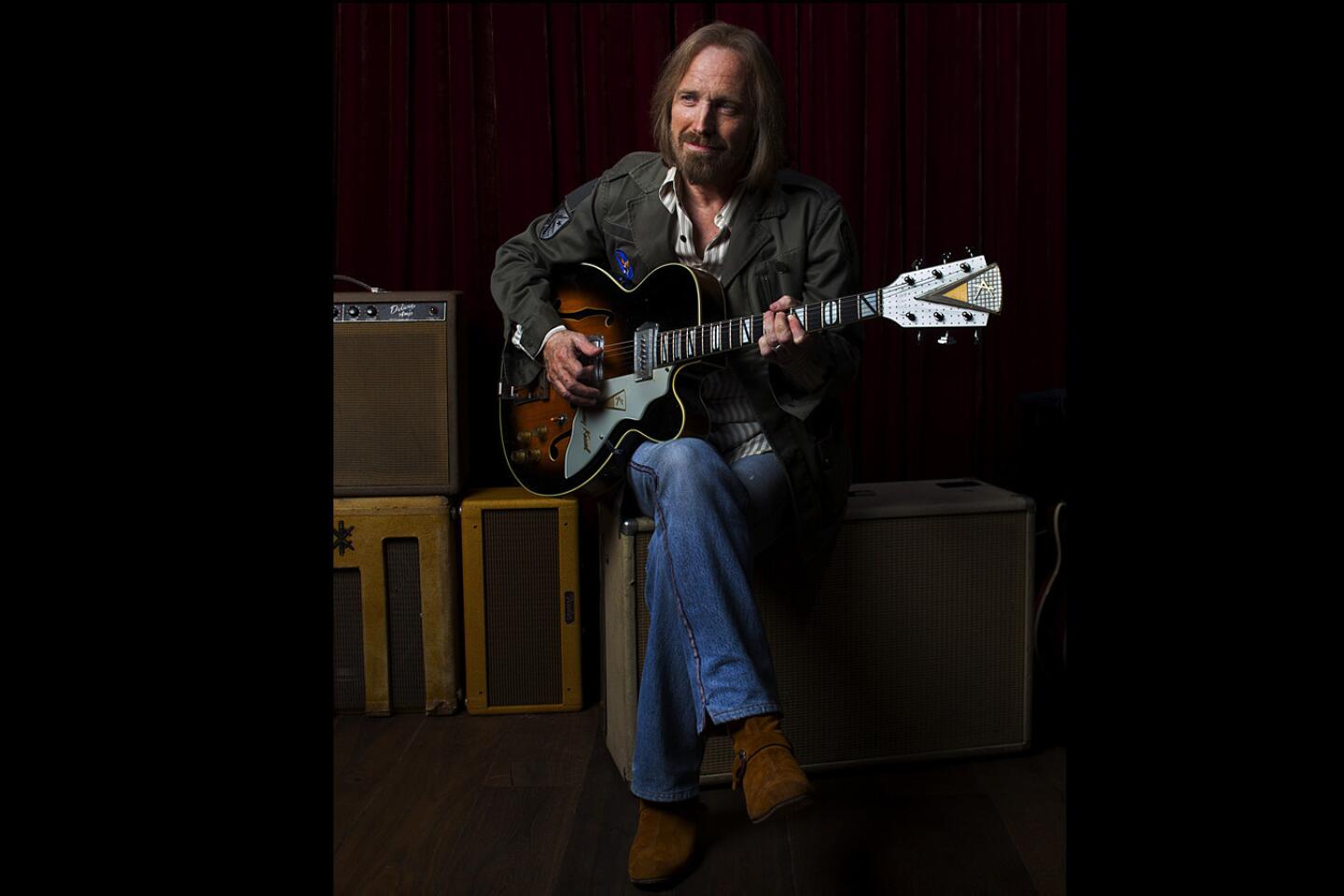

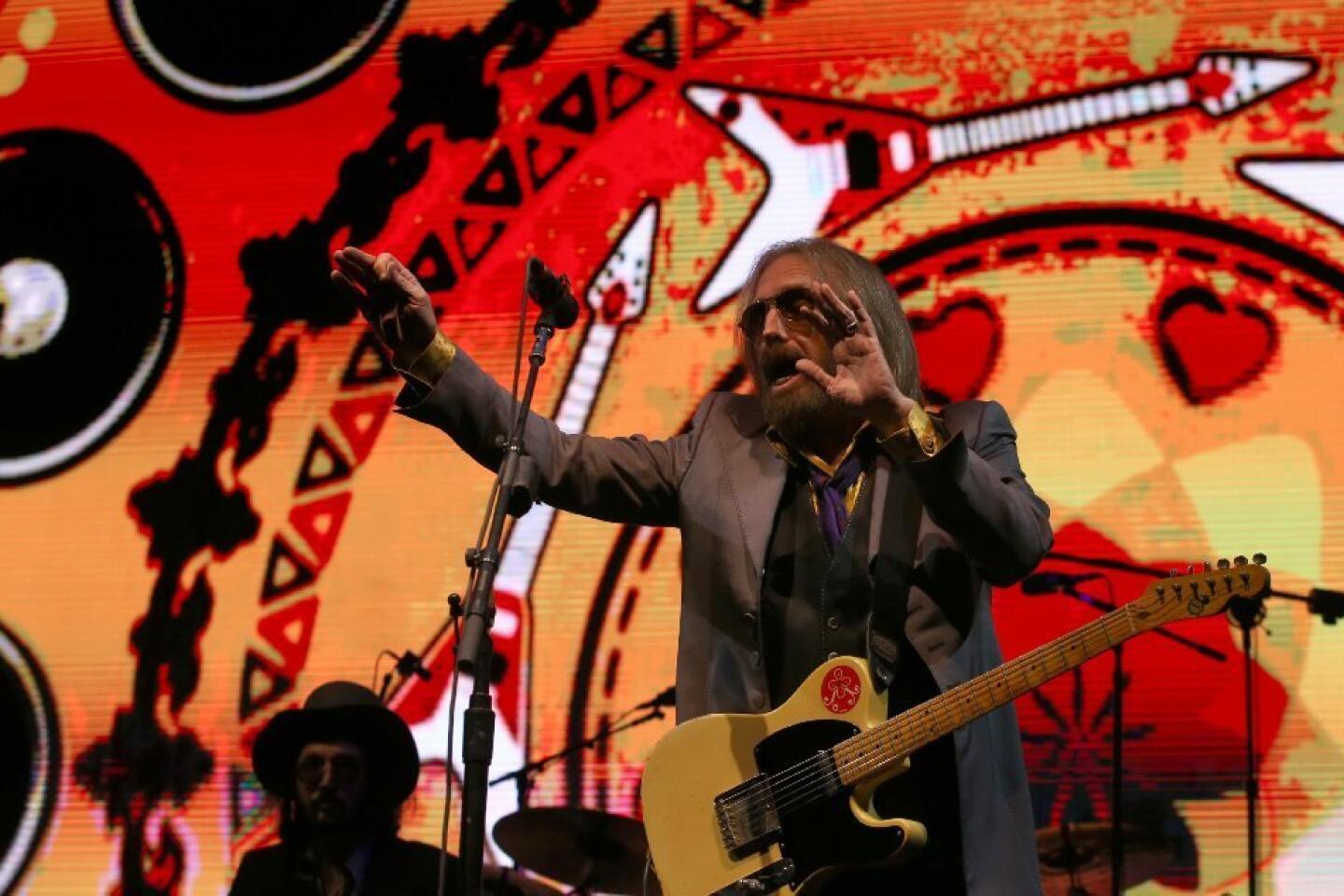

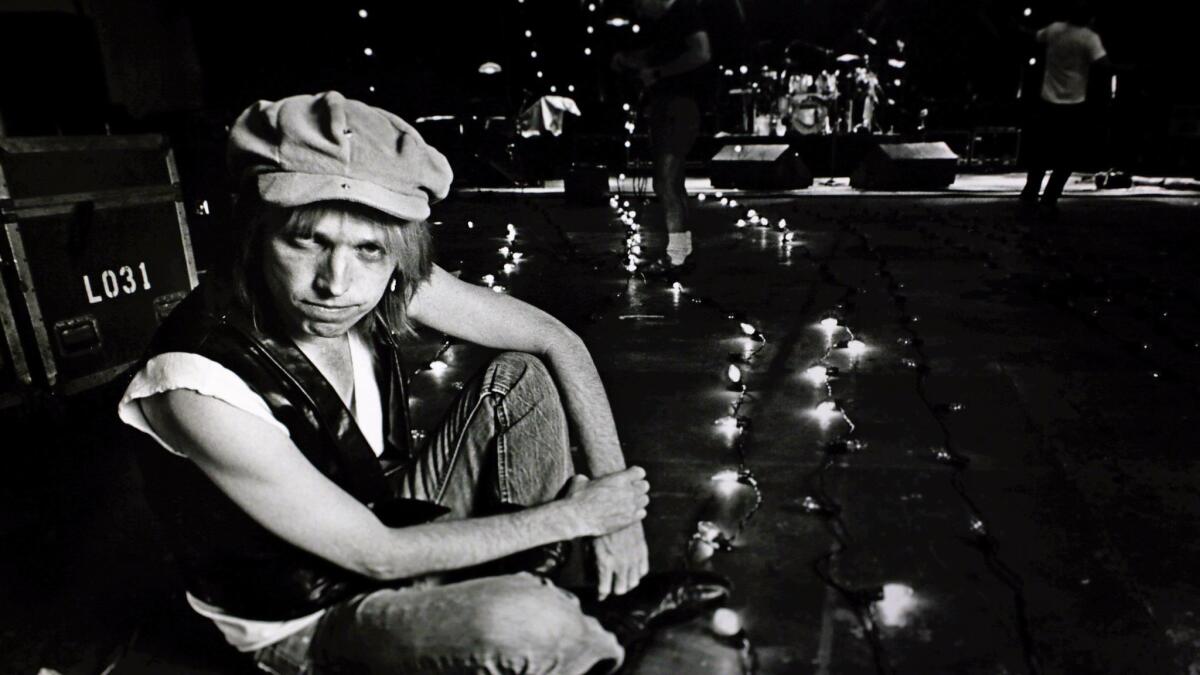

Singer-songwriter Tom Petty has died at age 66. In advance of his 1987 U.S. tour with his band, the Heartbreakers, Petty spoke to The Times about his excitement and renewed passions for music in relation to his new album “Let Me Up (I’ve Had Enough),” which included more socially conscious songs, and applauded the activism of his fellow musicians. This article was originally published on May 24, 1987.

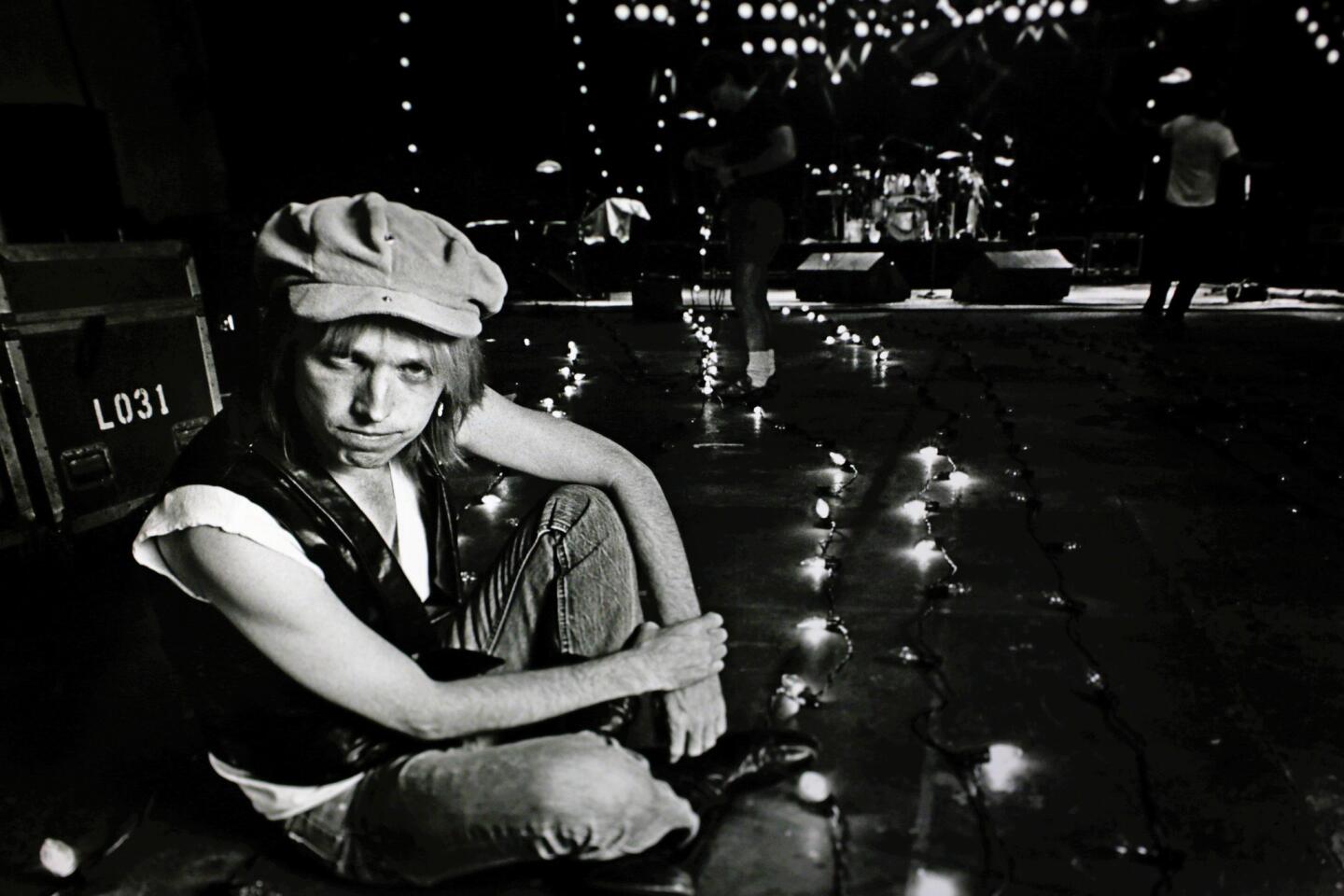

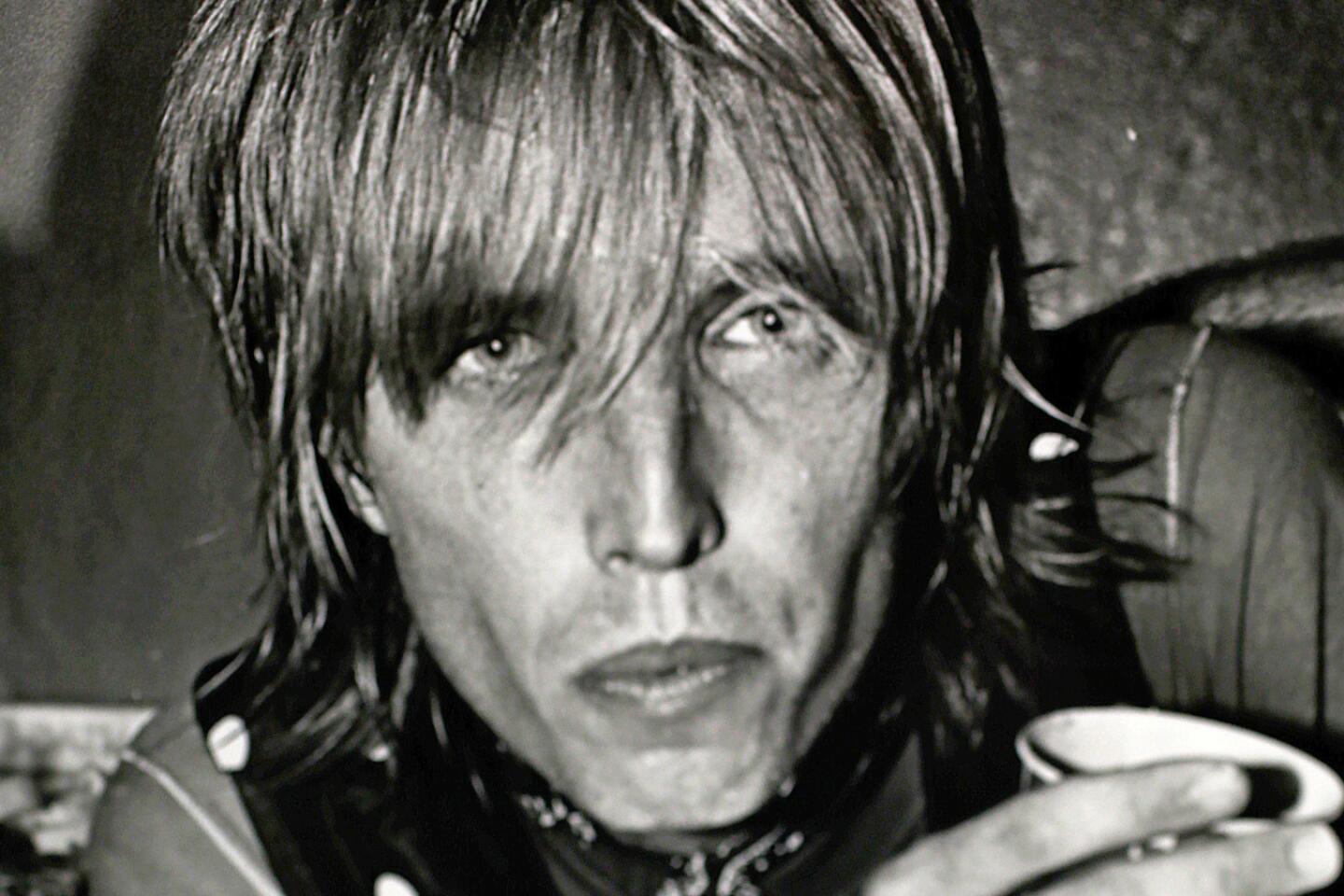

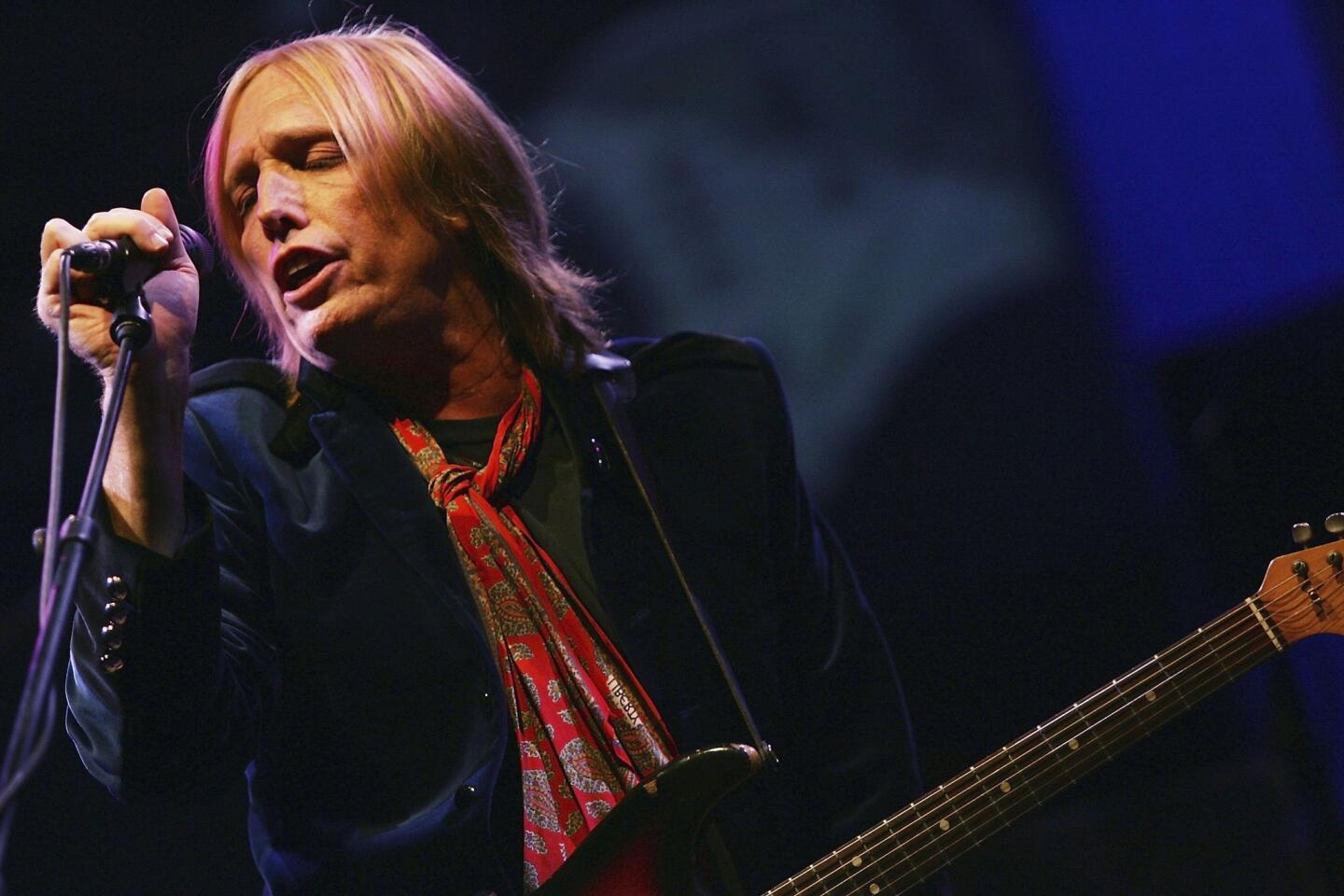

Tom Petty had no trouble describing his current mood as he sat on a sound stage at Universal Studios before a rehearsal with his band, the Heartbreakers. Eager, excited and renewed were words that came to mind.

Just two days before a fire destroyed his Encino hillside house, Petty was enthusiastic about his new album, “Let Me Up (I’ve Had Enough),” and a U.S. tour that begins Tuesday in Tucson.

(The tour, which includes stops June 6 at Pacific Amphitheatre and June 8, 9, 11 and 12 at the Universal Amphitheatre, will go on as scheduled despite the fire, which wiped out everything at the house except Petty’s basement recording studio, where his guitars and various master recordings were stored.)

Petty and the band were also looking ahead to more dates with Bob Dylan, whose 1986 shows with the Heartbreakers were among the year’s highlights in rock.

But it wasn’t as easy for the singer-songwriter to find the right word to summarize his mental condition during the time he was making “Southern Accents,” a 1985 work he now describes as “eccentric.”

Petty had already discarded the words disoriented, bored and disillusioned before settling on cloudy.

“Yeah, cloudy sums it up pretty well,” he said, rolling the phrase around in his mind. “A lot of things were happening at once and they all seemed to collide.”

Part of Petty’s problem back then was musical, and he spoke about that frankly and at length. But he appeared uneasy touching on some personal problems from that time. He’s tired, he said, of rock stars who talk about their problems in public, and he didn’t want to contribute yet another confession about the perils of rock’s fast lane.

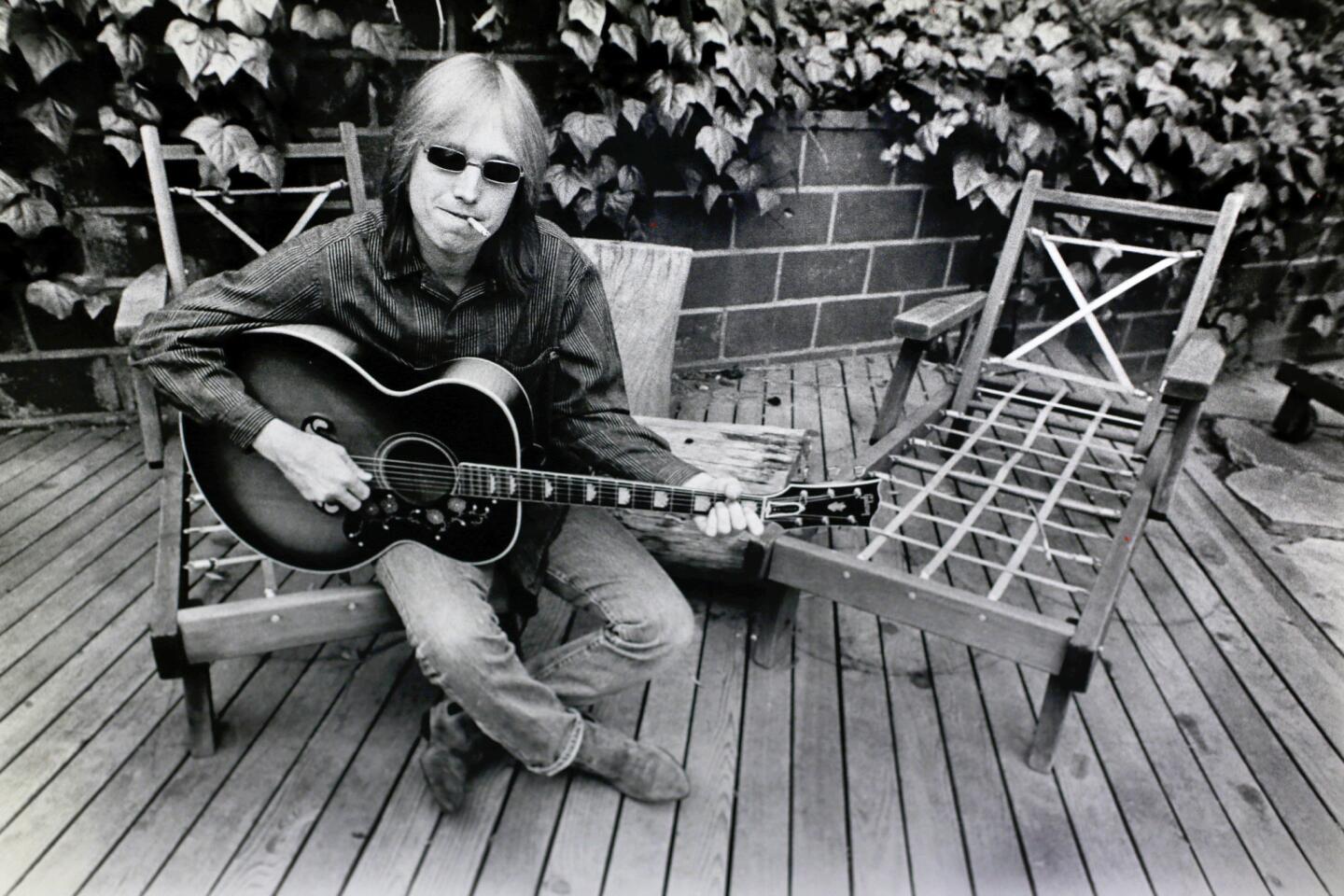

“Let’s just say I was living a strange life style. ... Up at night, sleeping in the day,” Petty said, sitting on a couch on the sound stage that houses part of the original “Phantom of the Opera” set.

“I had built a studio at home, which completely changed everything. . . . It was like running the best bar in L.A. . . . People always around. It started out innocently enough, but it got to be something that I never thought would happen to me.

“I mean, you could just look at us in those days to see we were confused. . . . Those little (psychedelic) glasses I started wearing. . . .

“But that’s been over for a long time now,” he said finally, shifting attention back away from his personal life. “Besides, it’s not the life style that’s important, it’s the music.”

Petty, a Florida native who has lived in Los Angeles for the last decade, paused and took a long draw from his cigarette. He’s not naturally talkative like David Lee Roth, who reels off quotable lines on whatever subject is raised. Instead, Petty struggles to answer questions, looking with a songwriter’s precision for the right image or phrase.

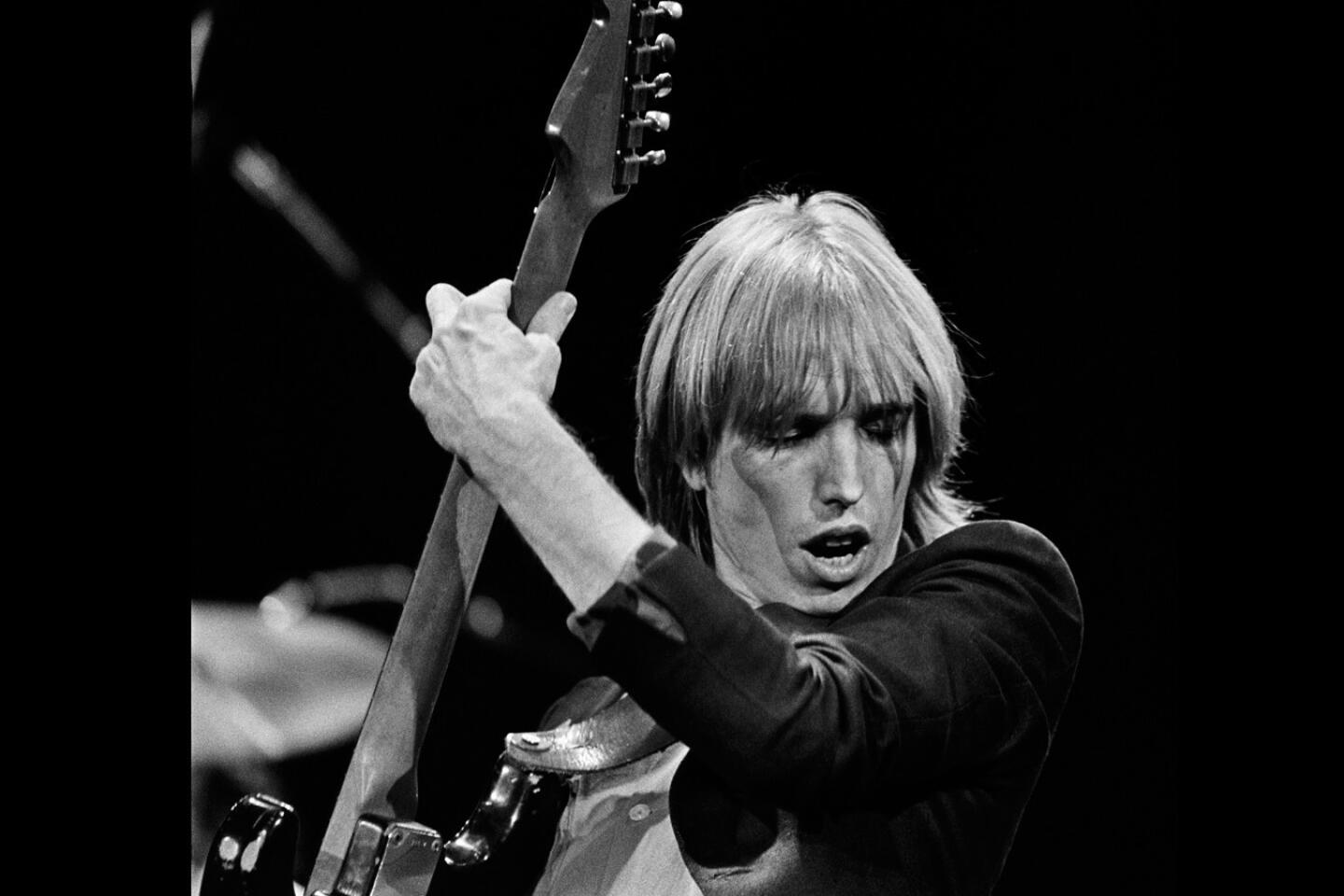

Petty said he started questioning the band’s direction around the time of 1982’s “Long After Dark” LP. He and the group had established a winning formula in “Damn the Torpedoes,” their 1979 best seller, and were beginning to stick to it.

Referring to “Long After Dark,” he said, “I didn’t even want to make that album. I liked a lot of the songs, but we seemed to be going for the same sound. I was worried that we were beginning to pander to the audience for the first time.

“I can see now that some of the passion was gone . . . and I don’t think we really got it back until we went on the road with Bob (Dylan).”

Like Bob Seger and Bruce Springsteen, Petty, 34, is a classic American rocker whose music combines the innocence and accessibility of the ‘50s (Elvis Presley was his first rock hero) and the more artful and ambitious themes that Dylan and other writers introduced in the ‘60s.

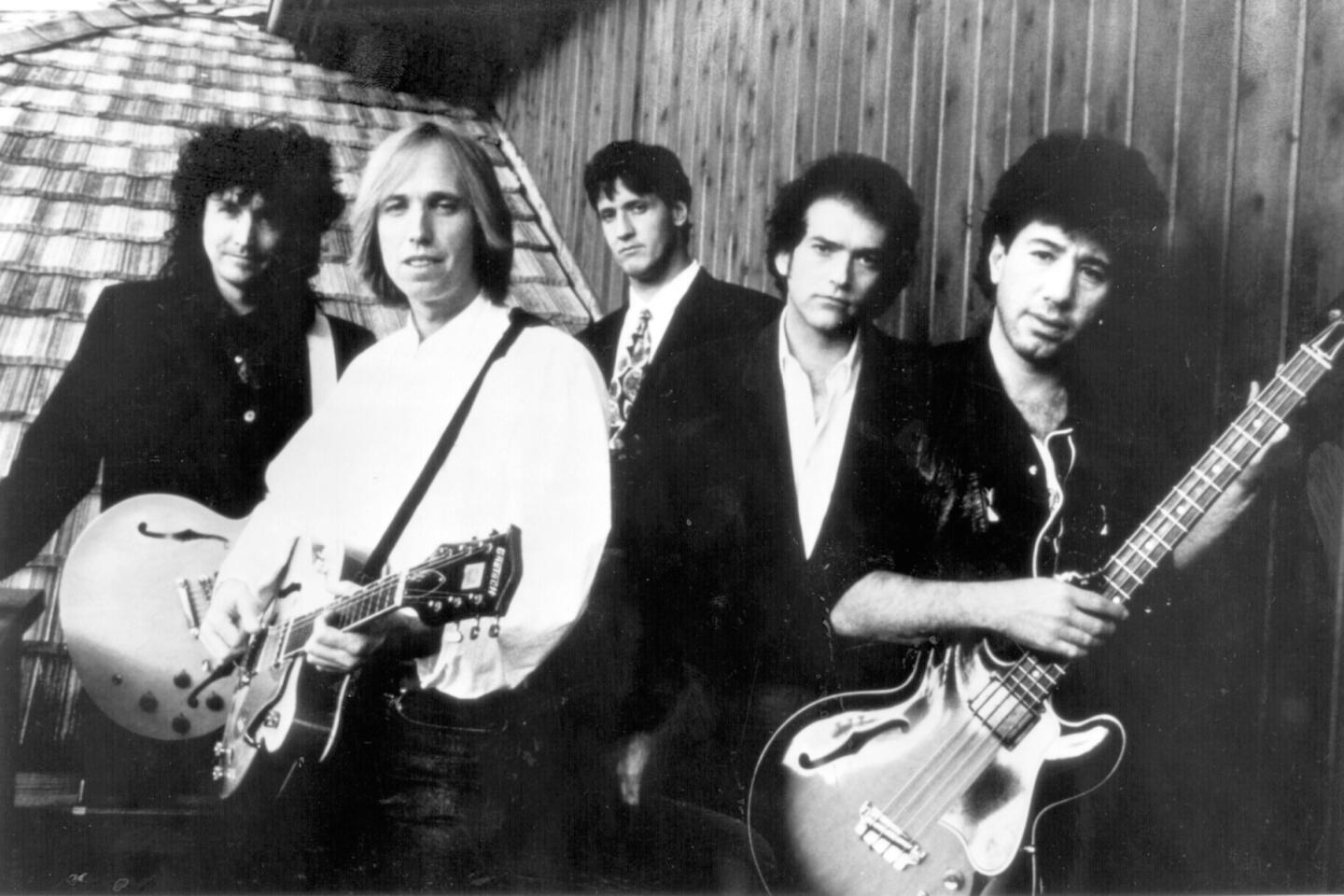

Petty and three of the Heartbreakers — guitarist Mike Campbell, drummer Stan Lynch and keyboardist Benmont Tench — knew each other in Gainesville, Fla., but the band was formed after they all hooked up again in Los Angeles in 1976. Bassist Howie Epstein is the only non-Floridian in the group.

The band’s first two albums were well received critically, though it wasn’t until “Damn the Torpedoes” that the group became a major commercial force. The album sold nearly 3 million copies.

Petty’s best early songs, including “American Girl” and “Listen to Her Heart,” were usually framed in romantic terms, but spoke about desire and faith in ways that went beyond boy/girl relationships.

Increasingly, however, Petty began to address those subjects more directly. Ironically, “Long After Dark” contained some of his best songs in this vein, notably “Straight Into Darkness.” But there was a perception that Petty was standing still because the arrangements on record seemed to sound the same.

After the “Long After Dark” tour, Petty wanted to take a break from the non-stop cycle of recording and touring. The other Heartbreakers got involved in outside projects, leading to rumors the group had broken up. But that was never even discussed, Petty said. “It was just time for us all to pull back from the table a while.”

Petty built the recording studio in his basement and began experimenting with new sounds and directions. Some of the songs — including “Southern Accents” — turned out to be among the most personal and affecting he had written, but Petty ended up spending so much time in the studio that he lost perspective. He felt burned out.

During this time, Petty met Dave Stewart of Eurythmics. Stimulated by Stewart’s songwriting and recording techniques, Petty asked him to produce some tracks for “Southern Accents.” He then combined those lighter tracks with earlier recordings that were tied to the concept of Petty’s Southern roots.

“Dave makes records like taking Polaroids, and that was good for me,” Petty explained. “I needed to start feeling some results. He has turned out to be a very good friend of mine and a neighbor.

“But I think it would have been smarter to stick to the ‘Southern Accents’ stuff,” he said, referring to the parts of the LP that dealt with his Southern roots, “or done an album with Dave, but not mix them. I can see why people thought it was a very quirky or eccentric album.”

Petty enjoyed the “Southern Accents” tour (which included a horn section and backup singers), but he and the Heartbreakers still weren’t ready to begin a new album when they came off the road. The cloudiness, he suggested, still lingered. Rather than go into the studio, they bought some time by putting out a live LP.

Some of the Heartbreakers had played in the studio with Bob Dylan, and Dylan asked the whole group if they would join him on stage at last year’s Farm Aid concert in Illinois. The Heartbreakers were already scheduled to perform at Farm Aid, and they invited Dylan to one of their rehearsals at Universal.

“We played for maybe four hours . … every kind of song,” Petty said. “It was a great time. So we had some more rehearsals and they, too, were fantastic. We all felt comfortable immediately. One thing Bob taught us was not to dwell on one song in rehearsal.

“There were nights when I bet we played 50 or 60 songs, which keeps you fresh. I used to go away from rehearsals feeling drained because we would go through a song over and over again, but now I went away from those rehearsals feeling invigorated. It was fun again.

“The funny thing is everybody always talks about what a great songwriter Bob is, so the thing that struck me was how very good a musician he is, too. He hears things right.”

That spirit continued when Petty and the Heartbreakers joined Dylan on the road.

“By the time we got out on the tour with him in Australia, I just felt really free for some reason,” said Petty. “Everything was clear again. I was so busy focusing on playing well that I forgot about all my problems. I was enjoying music again. I realized that I was worrying too much about pleasing other people or being accepted. I realized that the important thing is to feel good yourself about what you do, and usually if you like it, other people will too.”

The band had some time off before the American leg of the tour and everyone was feeling so good that they went into the studio.

They only had about three songs written, but they ended up cutting more than two dozen tracks over the next four to five weeks. The group’s “Let Me Up” album was taken from those sessions. The band’s playing bristled with intensity and desire.

As a songwriter, the best thing I can achieve is to get someone to think about things. I can’t give them the answers.

— Tom Petty

The material ranged from songs that have a familiar Petty ring to them (the delicate “It’ll All Work Out,” a ballad about a troubled marriage) to a series of socially conscious “character sketches” that represent a change of writing style. The latter include “My Life/Your World,” a reflection on what Petty sees as today’s restless, rootless generation: “My momma was a rocker way back in ’53 / Buys them old records that they sell on TV / I know Chuck Berry wasn’t singin’ that to me.”

About shifting from first-person anthems to character sketches, Petty said, “I found that when you invent a character, you can say things you might not be able to say otherwise. If I am trapped into singing the ‘Tom Petty creed,’ I am limited. I can’t experiment or express ideas that might not reflect my thinking at all.

“As a songwriter, the best thing I can achieve is to get someone to think about things. I can’t give them the answers.”

Petty applauds the activism of contemporary rockers. “I feel a little restricted with love songs now,” he said. “At one time I didn’t, but I just think there is too much going on to ignore it, and I think Live Aid showed us the power that musicians have now. To me, Live Aid was a pretty dreadful show if you had to take it on musical content alone, but the intent was fantastic.

“Sure, some people are saying we’re having too many benefits in rock, but I’d much rather see us (guilty of) that than the other way.

“I remember in the ‘70s when people were embarrassed to even discuss social issues, much less sing about it. They were busy taking Quaaludes and going to the disco. I think there is a lot of confusion in the world today and that’s what a lot of the songs are about. But I didn’t want the album to come off as a political lecture, so I invented characters and sneaked them into the songs.”

Petty’s renewed enthusiasm is also reflected in the choice of the bands that’ll be joining the Heartbreakers on the first leg of the U.S. tour: the Georgia Satellites and the Del Fuegos, upcoming groups that have been identified with the recent renaissance in basic, roots-conscious American rock.

“I don’t see it as an American thing,” said Petty. “These are just bands that base what they do around songs, guitar and drums for the most part … as opposed to a lot of groups these days that are either instrumental virtuosos or stress the fact that they are oddballs or have weird hair … that kind of thing. I guess you just call it non-gimmick rock, which is what we’ve always tried to do.”

ALSO

From the Archives: Tom Petty breaks down 10 of his songs, including big hits and obscure gems

Tom Petty and the Heartbreakers, an L.A. band, stare at ‘Hypnotic Eye’

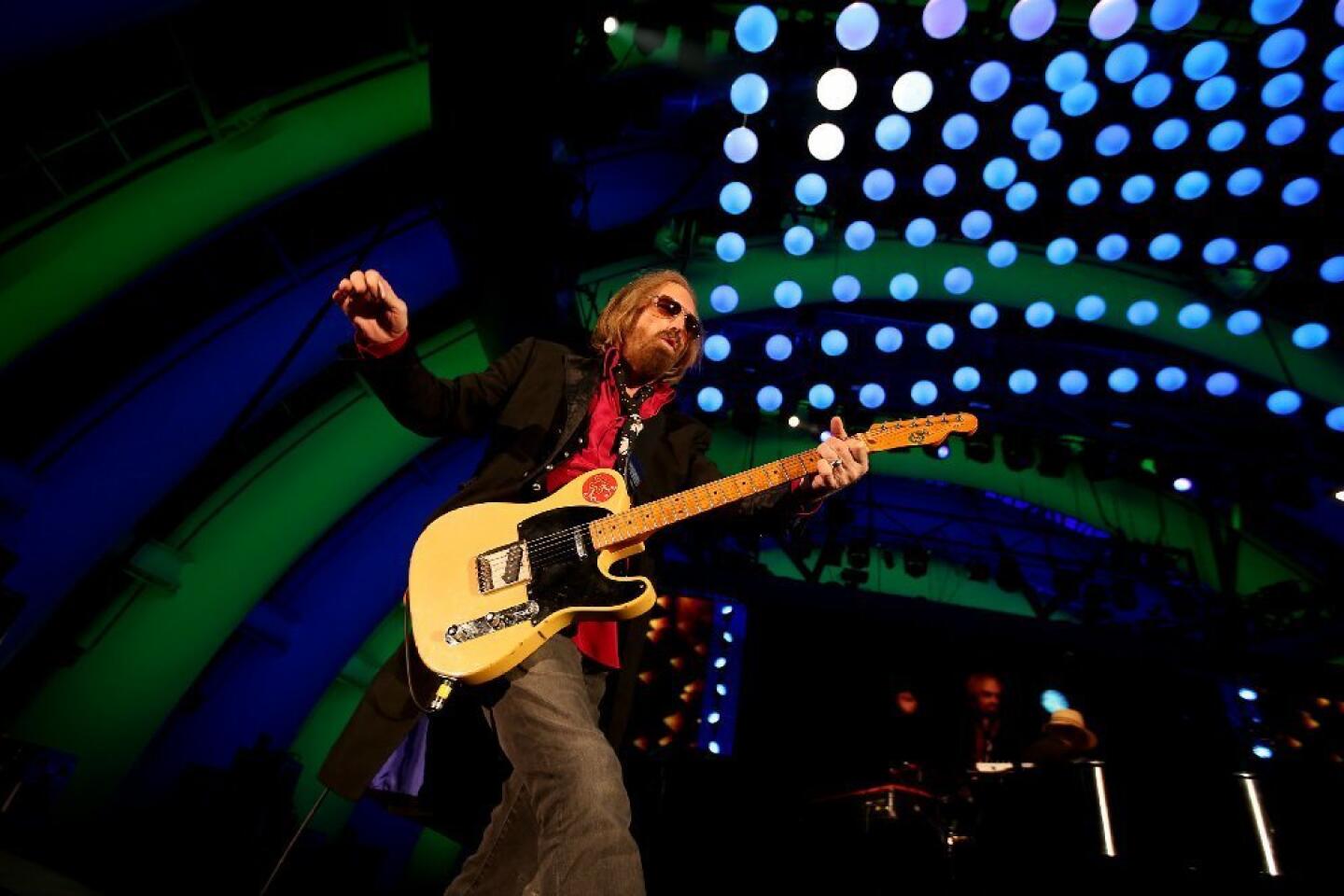

Review: Tom Petty and the Heartbreakers look back on four decades, but leave the nostalgia at home

More to Read

The biggest entertainment stories

Get our big stories about Hollywood, film, television, music, arts, culture and more right in your inbox as soon as they publish.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.